European nations spent much of 1909 feuding over the Balkans while the United States was focused on Central America especially Panama where the first concrete was poured to build the massive locks of the canal.

The first concrete pour for the canal locks 1909

U.S Navy Lieutenant Frederick Collins of Calais led surveying expeditions across Nicaragua to determine if that route was preferable to the Isthmus of Panama. His remarkable career and experiences during these expeditions were the subject of a prior article. The United States sent gunships to Nicaragua in 1909 to “protect American citizens” when the political situation seemed to be turning against U.S. interests in what was just one of many such military actions during the so-called “banana wars.”

Women were targeted by many patent medicines

In this country the income tax was instituted and opium finally banned after it was discovered that patent medicines had, for the most part, only opium, cocaine and alcohol as active ingredients and many, especially women, were addicted. Local drug stores also sold such popular remedies as “Cocaine tooth drops”. In sports the Indy 500 racetrack opened, the Red Sox traded Cy Young and Ty Cobb won the home run title with 9 homers—all inside the park. Robert Peary’s claim to have reached the North Pole was accepted as fact although it has since been called into question.

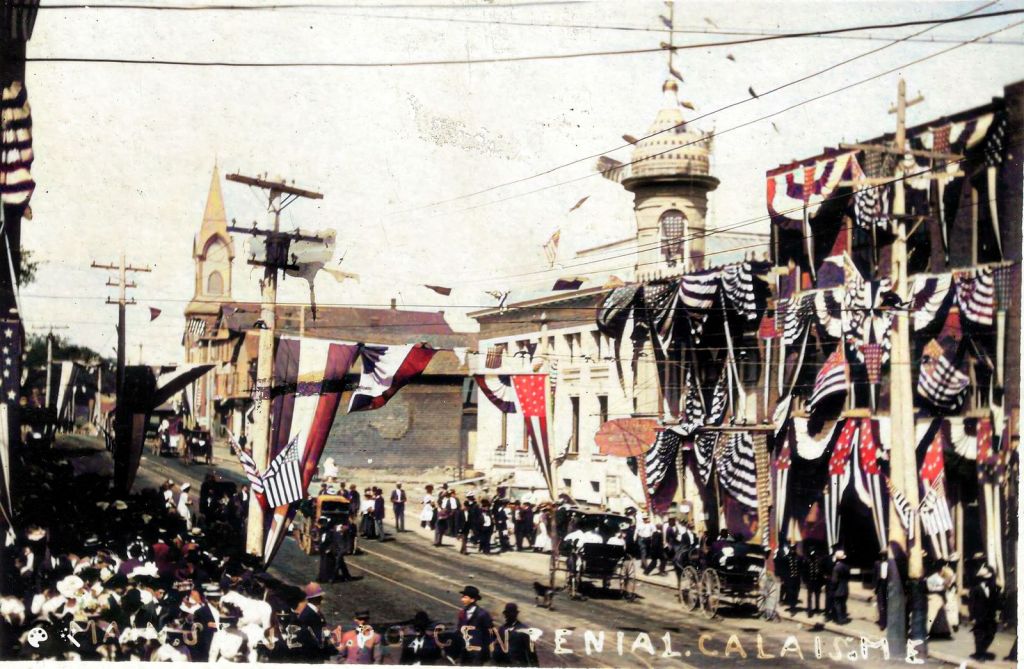

The newly built Post Office had just opened in Calais in 1909

Main Street from North Street looking east. Crumbs in now the center of this block

In the St. Croix Valley, Calais got a new Post Office on Main Street and Calais celebrated its Centennial with a week of parades, events and parties. The first photo above shows the new Post Office and what most recall as the Calais Federal Building decorated for the Centennial which drew many thousands to Calais for a week of celebration.

Chinese immigration was an issue in 1909

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 which prohibited Chinese immigration remained in effect in 1909. The Calais-St. Stephen border crossing was one of the more popular entry points for the Chinese who found it relatively easy to emigrate to Canada. A $100 entry tax had to be paid upon arrival in Canada, but this didn’t deter many immigrants whose final destination was the United States, often across the Ferry Point Bridge in Calais. Ironically the two Chinamen arrested on the streetcar entering Calais from St. Stephen almost certainly were travelling with St. Stephen residents illegally going to work in Calais. When the streetcar returned to St. Stephen many passengers were likely Americans illegally going to work in St. Stephen. There was constant tension between local authorities and the national governments over the lack of enforcement of the “Alien Labor” laws. Both the United States and Canada strictly limited such “Alien Labor” but the local economy was so integrated that enforcement of the laws would have put such industries as the Cotton Mill in Milltown, New Brunswick out of business. The solution was to simply ignore the laws except, of course, when it came to the Chinese.

It wasn’t that local authorities were too busy to enforce the laws. There were only 10 arrests in Calais for the entire year, and the City Council was a bit distressed that fines collected had amounted to only $17.86. This may have explained the rather ugly dispute over whether to furnish the Milltown, Maine night watchman a ton of coal to keep a stove going on cold winter’s nights. Several thought this any unnecessary luxury; but the motion to buy the coal eventually passed by a narrow margin. One of the ten arrests made by the City Marshall was Arthur Casey who was running a gin joint in Milltown, Maine. He initially escaped the long arm of the law by hiding from the Marshall from January until September. However, it was known that one event Casey never missed was the Woodland Labor Day celebration. Casey showed up as predicted and was arrested by the Woodland Chief of Police.

A mentally ill man gave the St. Stephen police a good deal of trouble in 1909

The St. Stephen police had their hands full for a couple of months with a mentally ill man who had crossed the border from Calais and upon being taken into custody became violent. They wanted to turn him over to the Calais authorities who refused to take him because there was no proof he was an American. The national papers got involved, circulating descriptions of the prisoner. At one point he was thought to be Howard Conger from Cincinnati or Cleveland, but other papers reported “Mr. Conger, has a Roman nose while the proboscis of the St. Stephen prisoner is rather inclined to be flat”. Conger’s brother visited the jail and assured the authorities the man was not his brother. Finally, after a couple of months, the man was found to be James Bates of Belfast and U.S authorities were forced to take him off the hands of the St. Stephen police. Howard Conger of Ohio was never found although his father believes he was robbed and thrown into the Atlantic from a steamship traveling between Boston and New York. His father was one of the wealthiest men in Cleveland and never gave up searching for his son.

The Tanning Company was at the bottom of Steamboat Street

One local crime did get some press. A trio of local crooks planned to rob the Calais Tanning Company on Steamboat Street one August night in 1909, but the owner of the company was tipped off and had three extra watchmen on duty. When no thieves had made an appearance by two in the morning the watchdogs went home to bed. The thieves took advantage of their departure and stole 600 pounds of wool which they transported across the river to the Canadian side. They hid the wool in the woods directly across from the Tanning Company and went home to get some sleep. That evening they rented a wagon from the St. Croix Hotel stable and crossed the bridge to pick up the wool but when they arrived at their stash, they were arrested by the St. Stephen police who had found the wool early that morning. Frankly it is hard to take sides in this slapstick “Keystone Cops” affair.

Another less amusing incident of 1909 involved the annual inspection of the Steamship Viking. The Viking had plied the river for decades, a workhorse beloved by many. Tied up on the Canadian shore in St. Stephen she was undergoing her annual inspection when the ship began to take on water. As the fires were out in the boilers the steam pumps were not operating and the ship went quickly to the bottom at the St. Stephen public landing. The captain of the ship and the six crew just managed to escape ashore. The incident presaged a much more tragic event which was to occur a few months later, one of the greatest tragedies in Downeast maritime history.

The rocky shore of Grand Manan

Walking along the high cliffs of Grand Manan while looking over the edge when the sea is wild and the waves are crashing against the rocks and cliffs below are a moving experience and one not soon forgotten. The majesty and power of Mother Nature is awe-inspiring but also somewhat unsettling, even from the island.

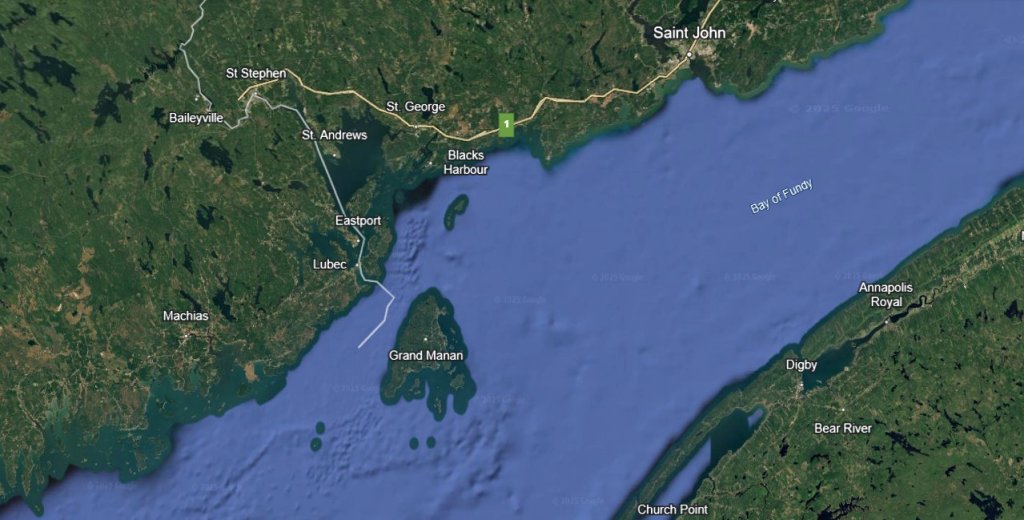

Grand Manan straddles the Bay of Fundy

For the mariners of yesteryear approaching Grand Manan in rough seas and high winds at night could strike fear in the hearts of even the hardiest sailors for as beautiful as Grand Manan may be, its rocky shores straddle the entrance to the Bay of Fundy and the island must be passed to reach St. John and the other ports on the bay.

Shipwrecks on Grand Manan

Hundreds of ships have been driven by the winds and waves against the cliffs and onto the rocks of Grand Manan. It is said that while the coastline of Atlantic Canada is known to be dangerous, that of Grand Manan is deadly. The more notable shipwrecks on Grand Manan are shown on the map above which is on display at the Grand Manan Historical Museum.

Steamship Hestia

Late on the night of October 25th, 1909, the steamship Hestia, sailing from England to St. John, struck the “Old Proprietor Ledge” just off Grand Manan and being in danger of sinking the order was given by the captain to the 36 sailors and four passengers aboard to abandon ship. The four passengers were young boys from Europe who had been sent by their families to work on farms in Canada. Thirty four managed to board lifeboats and six crewmen were left behind because the lifeboats were full. Only the six who clung to rigging of the Hestia survived.

Headline from Buffalo News

The wreck of the Hestia was reported throughout the world. Typical of coverage was the Buffalo News:

Buffalo News Hestia 1909

By Associated EASTPORT, Me., Oct. 27.-

A list of the 35 persons missing and believed to have been lost by the wreck of the Donaldson Line freight steamer Hestia, was made up today. It includes Captain Newman, First Mate D. McNair, Second Mate J. M. Phelan, Boatswain Ganigan, Ship’s Carpenter M. Colwell; Seamen John Smith, Breene, Murray, Chelson and McCangles, Apprentice Boy McDonald; First Engineer D. Munn, Fourth Engineer Best and Storekeeper W. Warneck. The names of the others are unknown.

Beyond a shadow of a doubt, in the opinion of the survivors, the 34 members of the crew, Captain Newman and those in their boat after the steamer struck the ledge, are lost. A search for the bodies was instituted today, but it was thought unlikely that any would be recovered.

ST. JOHN, N. B., Oct. 27- In the hope of being able to pick up some of the crew of the wrecked Donaldson line steamer Hestia, a number of tugs and other craft put out from this port early today for Seal Cove, Grand Manan Island. The efforts of the volunteer rescuers centered on the location of one little lifeboat, which, overcrowded with men, was the last to leave the sides of the Hestia. It was the general opinion that the lifeboat had been blown out of the sea. The condition of the six men rescued by the life savers is pitiable. Third Mate Stewart broke down and cried and it was a long time before any information could be obtained from him.

The Eastport Sentinel reported:

Eastport Sentinel: October 27, 1909

Terrible Wreck at Grand Manan.

DONALDSON LINE STEAMSHIP HESTIA, FROM GLASGOW TO ST. JOHN, WRECKED

ON THE “OLD PROPRIETOR.”

The most terrible disaster of the sea in this vicinity for years occurred Monday morning early, when the Donaldson Line steamship Hestia, of 3700 tons, bound from Glasgow to St. John, struck on the “Old Proprietor,” off Seal Cove, Grand Manan, and 18 a total wreck, and 34 out of a crew and passenger list of 40, including the captain and every officer except the 3d mate and the 2d engineer, were lost.

The weather was very thick and while running in and at 1 a.m. she struck a shoal inside of the ledge. Two boats were quickly lowered, taking the passengers and part of the crew. The tackle on one of the boats parting, threw the occupants into the water. When the boat righted one man was seen on board of her, and two were rescued by those on board the ship. A pitiable sight was one of the boys drifting away, and beyond all human aid, heard above the wind calling for his mother to save him. Capt. Newham and the rest of the crew have perished.

Owing to the heavy sea and wind, the attempts of the Life Saving Crew, under Capt. Frank Benson, to reach the ship were ineffectual until 3 p.m. yesterday, when the survivors – 3d mate Stewart, 2d engineer Morgan and able seamen Keene, McKenzie, Smith and McVicar were taken off and landed at Seal Cove.

The vessel will be a total loss, and at the latest advice the cargo was floating out of her. This wreck, with its terrible loss of life will enter the category with the Lord Ashburton and Sarah Sloan, ships that found a resting place on the rock-bound shores of Grand Manan, and the ill-fated crews of which whose bodies were recovered on the island and for years have been carefully watched over by the sole survivor of the latter ship.

The cause of the disaster was much debated. Hestia’s surviving Third Officer Stewart charged that the Old Proprietor Ledge buoy had not been maintained as required by maritime law. According to Stewart, the buoy was listed on charts as having both a light and a foghorn, but it had neither on the night of the wreck. Further Stewart said the Gannett Head lightkeeper had seen the Hestia before the wreck and was aware of the danger to the ship but fail to discharge a firearm to warn the Hestia as “it might awaken the doctor sleeping in the lighthouse”. The ship being English an inquiry in London laid blame squarely on the captain for failure to take soundings as the ship approached Grand Manan. In a macabre twist of irony, the Hestia was carrying a load of cargo from England to St. John which included coffins.

Stewart owes his life to some brave men from Grand Manan who risked their lives in high seas to rescue them. A correspondent for the St. Andrews Beacon wrote:

I wish to say that the men who saved the six survivors of the wrecked Steamer Hestia on the day of Tuesday, the 26th were: Turner Ingalls and Leonard Benson, who were the first to go alongside the steamer Hestia and take off the first two men, and later another one, then Joseph, James Dalzelle and George Russel in another dory rescued three.

The six men who were rescued had clung to the superstructure of the steamer for over a day as the ship slowly descended to the bottom. The hull was entirely underwater by the time help arrived and, according to the Calais Advertiser, “they were utterly exhausted, having been clinging to the superstructure for hours with spray dashing over them.”

Much has been written over the years about the wreck of the Hestia including a 1937 novel by H.M.Tomlinson. Artifacts from the Hestia are on display at the Grand Manan Historical Museum and others rest on the ocean floor. Divers still visit the wreck which is in six to 10 fathoms of water although divers are warned that currents at Old Proprietors Ledge are very dangerous. Perhaps it is worth the risk. A perfectly good bottle of scotch was once recovered by a diver.

The Hestia was named after the mythological Greek god of Hearth and Home.