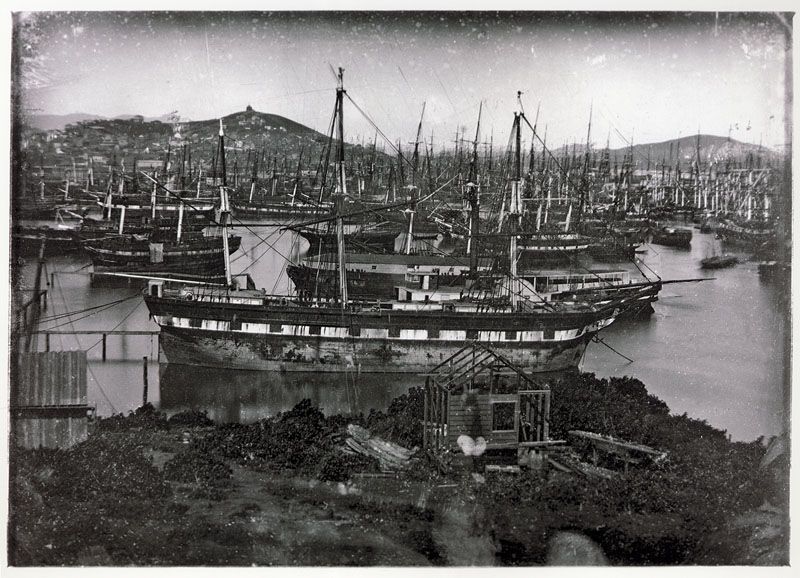

Abandoned Ships San Francisco Harbor Gold Rush

There was no lack of shipping in San Francisco Harbor during the Gold Rush in the early 1850s. The harbor was crowded with sailing ships of all kinds but nearly all of them were abandoned-their crews jumping ship to get rich in the gold fields in the interior. While only a few succeeded, nearly everyone tried including hundreds from the St. Croix Valley.

There was gold to be found in California, but the goldfields were not on the coast but inland. Sutter’s Mill where gold was first discovered was over 150 miles from San Francisco via the Sacramento and American Rivers. As ships under sail had a difficult time navigating both these rivers the business of transporting the miners and their supplies to the gold fields proved very challenging. It was also very lucrative. What was needed were steamboats which were both maneuverable and not dependent on the temperamental winds but the means to build steamships in California was limited. While a couple of small steamships were built from parts shipped around the Cape, steamships which attempted the Atlantic to Pacific route around Cape Horn at the tip of South American usually met with disaster, being either lost without trace or wrecked on the shores of South America. It took a sea captain and ship owner from St. Stephen to find a novel solution to the problem. It required the building of large sailing ship, the 700-ton bark Fanny and sinking it in the deepest part of the St Croix River at the Ledge, just below St. Stephen.

The Ledge Below St Stephen-Devils Head to right

William Vroon, noted local historian, described the process in a 1916 article:

It was Captain Henry Eastman, shipbuilder, of St. Stephen who conceived and carried out the idea of sending a steamer around the Horn in the hold of a sailing vessel – Captain Eastman’s yard was in the town of St. Stephen on the St. Croix river, which there forms the boundary between the State of Maine and the Province of New Brunswick. Here, early in 1850, the keel of the ”Fanny”, a bark of 700 tons, was laid down by Wm. Hinds, master builder, and in the fall of the same year the vessel was launched.

The Fanny was built with a view to carrying the steamer “S.B. Wheeler” as her first cargo, to California, and the means by which this was accomplished was ingenious and novel, as well as successful. The vessel was built with deck beams and knees secured by screw bolts which could easily be removed. After launching, she was towed to “the Ledge” a deep-water harbor on the St. Croix, and there ballasted with stones, was scuttled. It should be remarked here that the spring tides at this point rise and fall not less than twenty-six feet maximum.

At high tide, the Fanny’s deck beams having been removed, the steamer was floated over the sunken vessel and gently settled down into her hold as the tide ebbed, grounding as I was informed by an eye-witness, “within three inches of where Mr. Hinds wanted her.” At low tide, the holes in the vessel’s bottom were stopped and she rose with her cargo on the flood.

The S.B. Wheeler was a small steamer formerly plying between Eastport and Calais on the St. Croix. I have not been able to ascertain her tonnage or dimensions but know that her height from keel to deck about filled the space between the deck and keelson of the bark. The deck beams of the Fanny were replaced, some of them passing through the steamer’s cabin, the keel of the steamer was made fast to the keelson of the bark, and the masts of the latter were stepped on the steamer’s keelson. Ties and braces were inserted wherever necessary to prevent the possibility of shifting and the Fanny was rigged and made ready for sea. Coal was then stowed in the hold outside of the steamer which further contributed to the stability of the cargo.

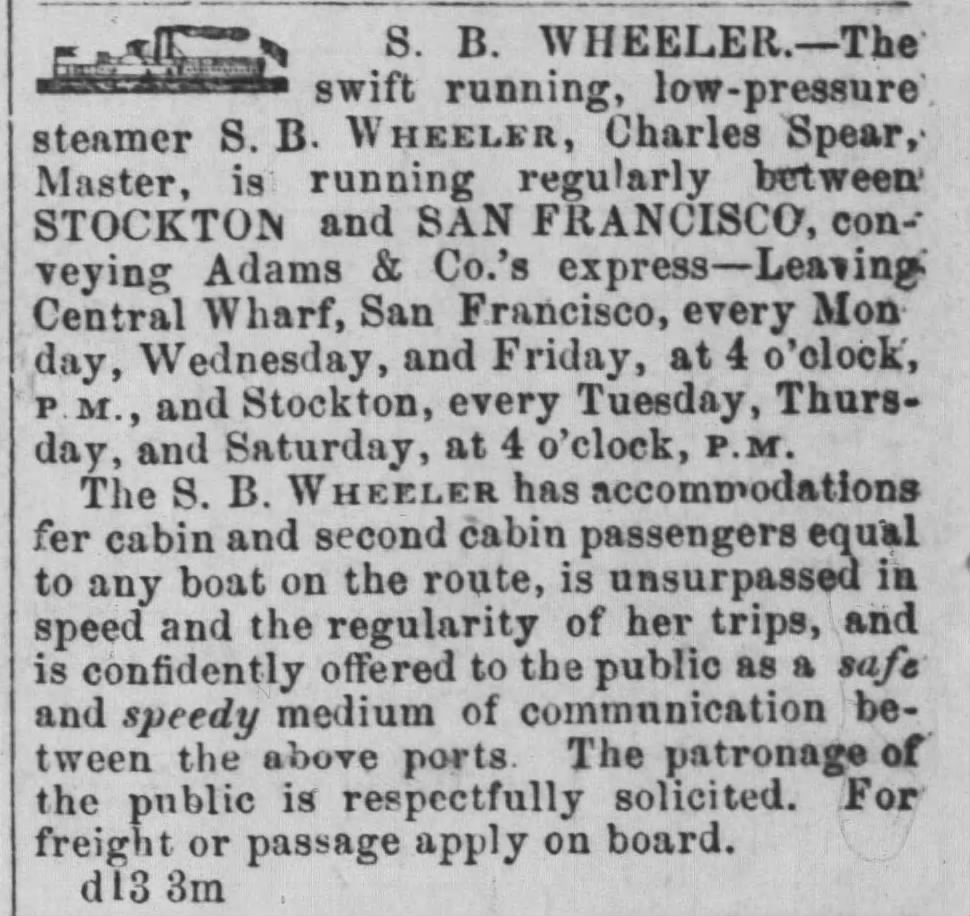

Local and national newspapers found the undertaking very newsworthy.

The Fanny, with the S.B. Wheeler in her hold, sailed from on December 24th, 1850, for San Francisco under the command of Captain Foster, an American and with several passengers from St. Stephen. She spent Christmas in Eastport. After a journey of 133 days, she reached San Francisco where the Fanny was again sunk and the Steamship S.B. Wheeler reemerged from the hold, ready for service in the Gold Rush.

The Fanny with the Wheeler in her hold arrived on May 12th 1851

She began regular service on the rivers of California

However, it was not her service during the Gold Rush for which the S.B. Wheeler is remembered. In 1853 she made history by becoming the first steamship to ply the waters of Hawaii.

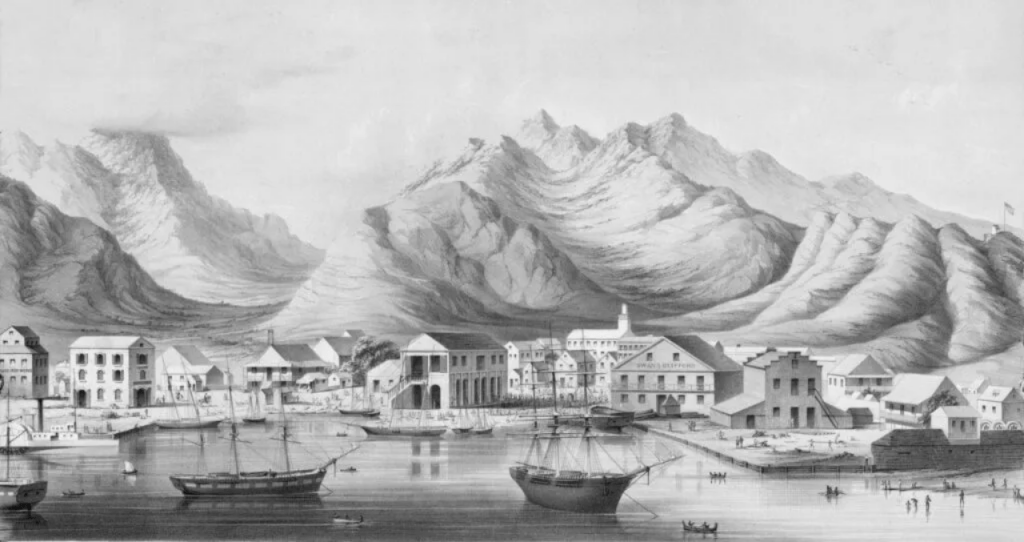

Harbor in Honolulu about 1850

For Hawaiians the Wheeler was a godsend. A steamship was ideal for transporting trade and passengers between the Hawaiian Islands but while promised to the islanders for many years the Wheeler, renamed the Akamai, was the first to do regular service.

The islanders were jubilant. The newspapers pronounced the Wheeler-Akamai a godsend.

From Shasta Courier: Nonember 12, 1853

ARRIVAL OF THE STEAMER.- -Our usually quiet town was enlivened on last Saturday afternoon, Nov. 12th, says the Honolulu Argus, by the announcement that a steamer was approaching our harbor. Hundreds rushed to the wharves, and every house- top was crowded to view the novel sight. It proved to be the Hawaiian Steam Navigation Company’s pioneer steamer, the S. B. Wheeler, designed for the inter-island trade. She approached and entered the harbor in gallant style and was received by those on the wharves with three cheers. She is a beautiful steamer, fine model, and has every convenience for passengers and freight, and is commanded by experienced officers. We give her a hearty welcome and trust our citizens will not fail to give her a liberal support.

The Hawaiian king and his family

The Akamai was an immediate sensation with the public. Pleasure cruises among the islands became a popular weekend excursion with 400 people on board and nearly as many disappointed Hawaiians left on shore, hopeful for the next trip.

From South Australian Free Press April 1, 1854

Akamai went on a pleasure excursion to Pearl River, having the King, the royal family, and a crowd of passengers on board. The company obtained a charter from the Government, for the exclusive steam navigation for ten years, on steam condition of keeping the island supplied communication, and also that another steamer, of about 850 tons, is to be immediately procured. On Saturday morning last, the Custom-house wharf presented one of those strikingly characteristic foot-prints of progress, which, once seen, can never be mistaken-one of those new features of a new era so radiant with hope and promise, The steamer Akamai lay alongside of the wharf with her steam up, a band of music playing, and ready to start on a pleasure excursion The wharf was crowded with people eager to take passage, and such a display of silks, satins, and parasols, is not often to be met with. After about 400 passengers had been admitted, nearly double the number were refused, the boat being unable being unable to accommodate any more. The trip lasted about four hours; music and dancing were the order of the day; satisfaction the consequence; the reputation of the boat established beyond a cavil; and we hope a most successful diversion given to the inveterate habit of promiscuous horse-riding on Saturdays. If the ship could possibly perform her trip to windward and so as to be able to devote Saturdays to similar pleasure parties from Honolulu, we would be inclined to look upon her advent as a greater auxiliary in the work of civilizing and humanizing than the united preaching on a month of Sundays.

Unfortunately, the Akamai could not long disguise her true nature-she was a river steamer not designed for the rough seas and winds which often buffeted the island’s shore. Further she was so popular that she was often overloaded with freight and passengers.

The Polynesian September 1854

The steamer AKAMAI, which sailed for Lahai on Tuesday evening, was obliged to return on Wednesday morning, having escaped foundering only by constant pumping and bailing. The occasion of this disaster was that she was greatly overloaded, having four or five hundred passengers and 19 horses on board. When she left it was with her guards underwater, and apprehensions were entertained by many that she would meet with some disaster. Had the weather been calm, she might have made the passage to Lahaina safely, where a large number of the passengers were to land; but about 10 P. M., she was struck by a squall, and the wind soon raised such a sea that she commenced leaking badly.

The pumps did not discharge the water as fast as it came in, and it finally came in on deck and ran down the hatches. In this critical situation, Capt. Lighthall got her about and succeeded in keeping her afloat until he entered the harbor. All her passengers were safely landed, with all their baggage, a result which was almost miraculous. From all we have recently heard of the Akamai, we are of the opinion that she is past service and should be condemned as unfit to convey passengers between the islands where the weather is often boisterous; lives should not be endangered by an old leaky craft that may some day, if permitted to run, send hundreds to the bottom.

At all events, the government should have a thorough survey made of her condition, by disinterested persons, and if she is unworthy, other and better boats should be substituted. We hear the SEA BIRD is now on the way from San Francisco to be put into the coasting trade and may be expected next week. We hope the news is true.

The Wheeler-Akamai was eventually retired to tugboat duty and on July 4th, 1857, the local newspapers reported her demise.

While her demise was unremarkable her life was distinguished. Born as a small river steamer on the St. Croix the S.B. Wheeler came to represent an important example of Downeast ingenuity. The Newport Rhode Island Times called her trip in the hull of the Fanny a “Yankee Trick” but she opened an important era in the history of Hawaii.