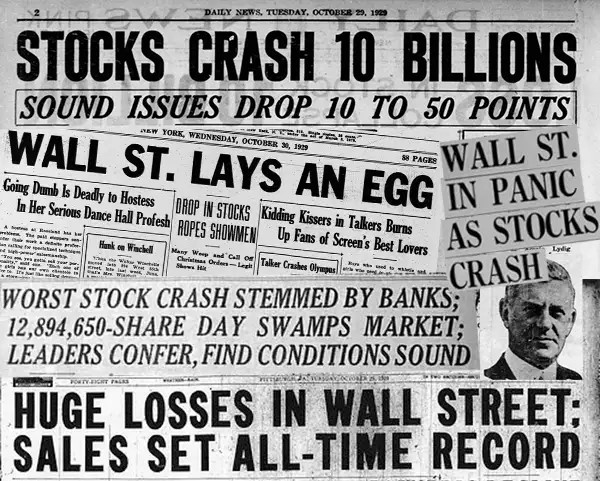

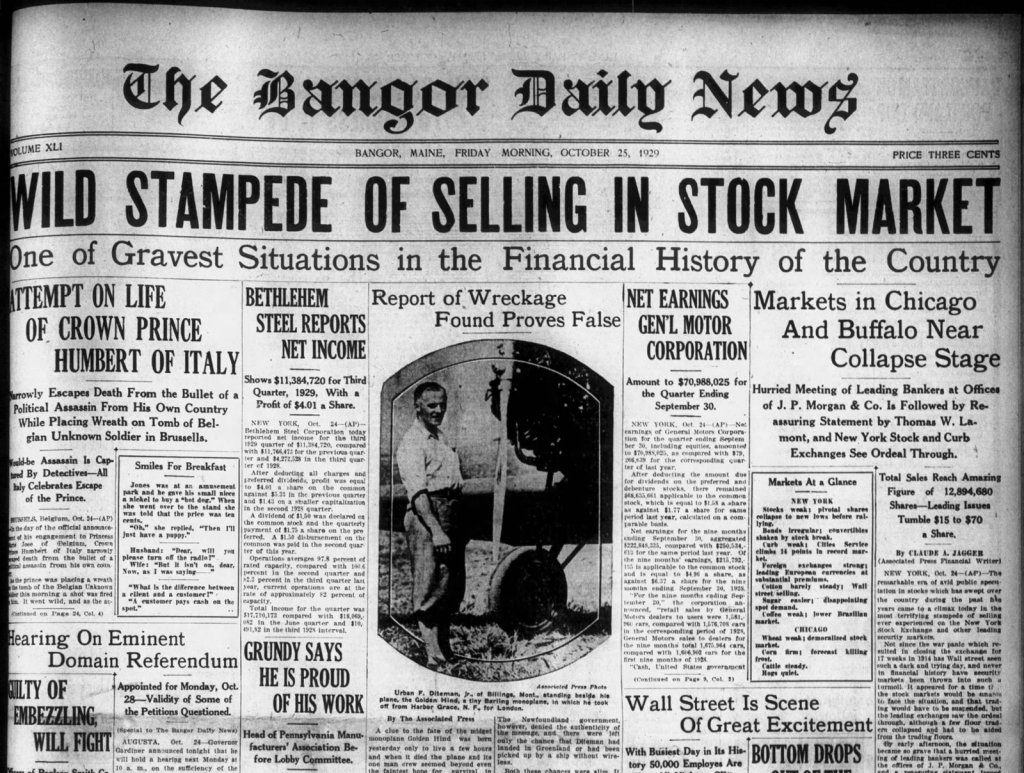

The Stock Market Crash began on October 25th, 1929

October 25, 1929 was followed by Black Monday and Black Tuesday and the rout was on

Few folks are around today who have any memory of 1929. Nonetheless the “Crash of 1929” evokes, even in those born decades later, images of desperate people in unemployment and soup lines, the stock markets “Black Monday” on October 28, 1929, followed by “Black Tuesday” the next day and the newspaper accounts of rich men, now paupers, leaping to their deaths from the Wall Street’s skyscrapers. Maybe the portents should have been evident months earlier when on New Year’s Day of 1929 when Roy Reigle picked up a fumble in the Rose Bowl and ran in the wrong direction towards his own goal as his teammates tried in vain to chase him down. Still, if this was an omen, it wasn’t apparent for most of 1929 which saw a soaring stock market, a telephone finally installed in the White House and the Tarzan and Popeye comic strips appearing in the papers for the first time. Babe Ruth became the first player to hit 500 home runs just days before the stock market hit its all-time high in September before crashing on Black Monday and the rest is history.

Following the lead of President Herbert Hoover, the Calais Advertiser was not much concerned about the economy, reporting that Hoover had met with the giants of industry and finance who assured Hoover that “the “Nation’s Business Was Sound” and “Unless President Hoover and the leaders of industry, finance and labor are all wrong, the country’s business structure is on a firm basis and there is no reason why prosperity should decrease despite the stock market collapse…” The following week the Advertiser reported Hoover’s plan was “Business as usual-and then some” while encouraging the Congress to cut taxes and urging Americans to tighten their belts and work harder. The dire headlines of October 1929 were followed by complacency until it was too late to save the economy.

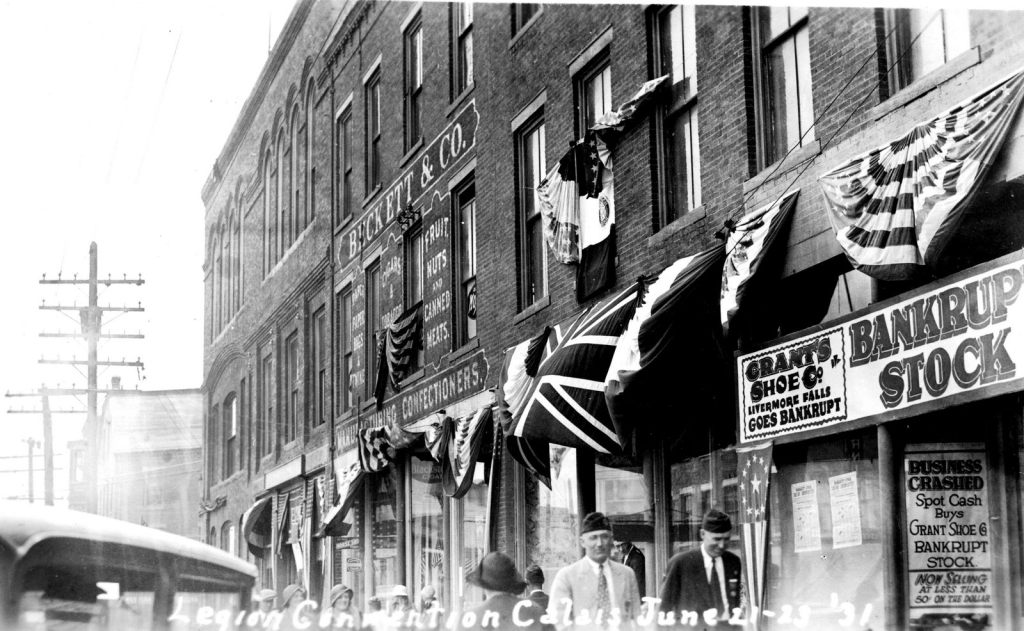

Calais businesses soon began to go under

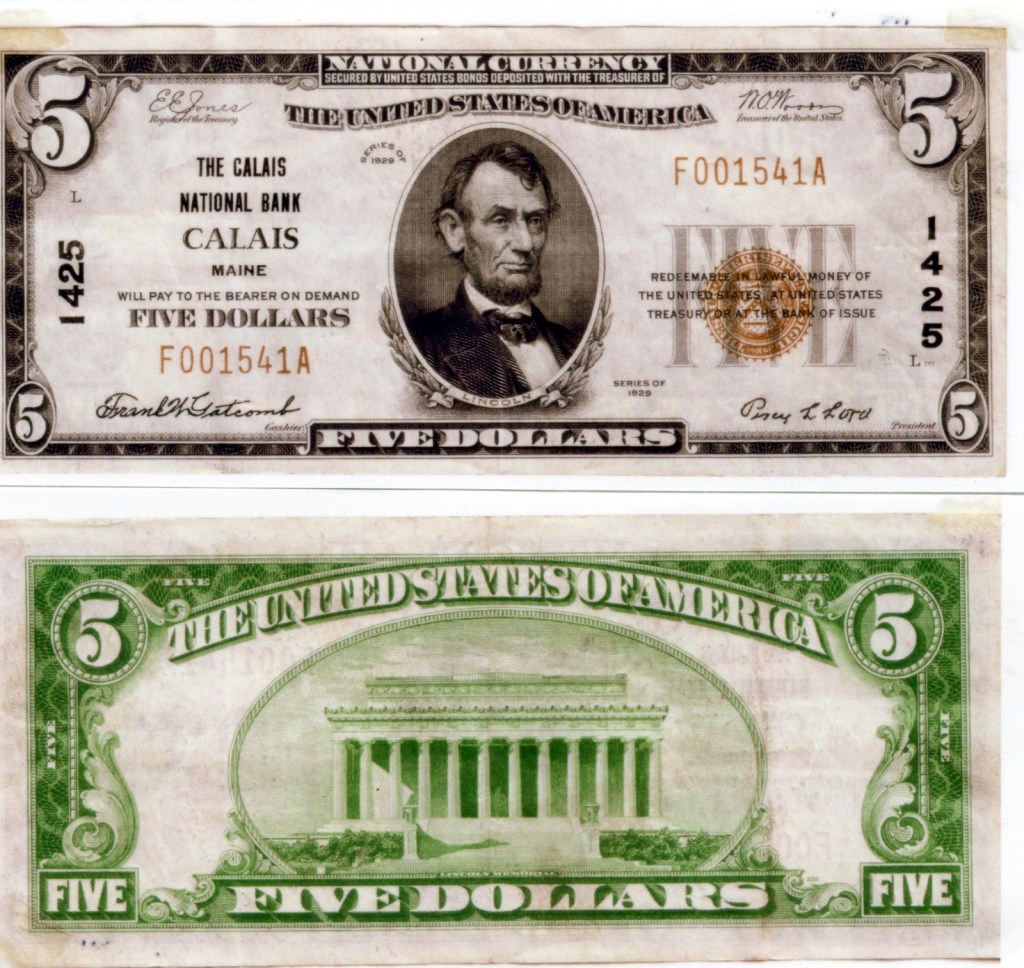

A five dollar bill issued by Calais druggist Percy Lord and Frank Gatcomb,bank treasurer

As the Depression deepened in the early 1930’s many businesses and banks collapsed and the money supply contracted. Local banks were allowed to issue their own currency which could take any form but usually replicated the bills then in circulation such as those pictured above.

The signatures under Abe’s picture were those of Percy Lord and Frank Gatcomb Calais businessmen who also happened to be officers of the Calais National Bank. Percy Lord owned the drug store just up the street from the bank and was for many years its treasurer. In the photo his drug store is to the right of Beckett and Company. Frank Gatcomb was the chief cashier of the bank. Like most banks in the country during the Depression years the Calais National Bank was on the ropes and did not have the funds to pay depositors because there was a great shortage of money, in this case paper money, as the federal government wasn’t printing any. In desperation, the feds gave local banks the right to issue currency in order to increase the money supply and hopefully grease the wheels of the economy. Theoretically the local “money” was backed by assets deposited with the Treasury of the United States—says so just above Abe’s head on the bill—although few in the early 30’s would have taken that to the bank and if they had would almost certainly have left empty handed. And there was this- how much confidence can you have in a five-dollar bill issued under the authority of a friend or acquaintance who maybe can’t beat you at bowling or cribbage? Would businesses in Machias or Bangor accept the bill? It seems unlikely.

The Calais Bank held on until 1934 before going bust. The other bank in Calais at the time was the International Bank and Trust Company, which experienced similar problems. It held a note for $4500 from the St. Croix Country Club. The club couldn’t pay the note and was forced to reorganize to raise the money which wasn’t easy even for such a well-heeled group of local businessmen. Perhaps the club was forced to drop the prohibitions against dancing in the clubhouse on Sundays and sending house servants outside on errands as part of the reorganization. Many civic organizations were unable to continue operating as donations dropped or ceased entirely. The Pembroke American Legion was unable to repair the Legion Hall, and the group ceased meeting for many years. On a positive note, the Boston Braves were so hard up for cash they went on a barnstorming tour which included a game in St. Stephen with St. Stephens legendary Kiwanis team. Calais’ Ken Kallenberg, then only 16 started the game for the locals.

Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) in Charlotte

Local towns found themselves in a financial bind. Their accounts in the Calais National Bank were closed until the bank reorganized and briefly reopened in 1934 as the National Bank of Calais although with reduced balances in the accounts. Merrill Bank eventually bought the bank in the early 1940’s.

Grace Hatton, Charlotte historian describes the situation in Charlotte as follows:

Roosevelt was inaugurated March 4, 1933. He went into action swiftly and vigorously. His first official act was to declare a “banking holiday.” Banks found in good financial condition were allowed to reopen, which gave the people confidence.

How was all of this playing out in Charlotte? The town was doing business with the Calais National Bank — its loaning power, its checking system, and cemetery trust funds. On May 16,1934 this bank reopened under the name National Bank of Calais. The L. W. Gardner cemetery trust fund account, which was first opened April 1, 1920, with $100, was reopened with a principal of $89.54. In October 1935, over fifteen years after the account was opened, the bank added $21.46 to its principal, bringing the total back to the original amount. Two other accounts were treated in a similar manner. Issued checks that had not cleared the bank before the holiday amounted to $378.83. The town now looked to private individuals for loans.

The President soon realized the problem was more than a banking crisis. Factories, mills, and mines throughout the country were closing. Farmers could not make their payments. In 1932, the one industry in our area, situated in Pembroke just over the Charlotte line – the Washington County Canning Company — was reported not to open that summer. This had been a source of seasonal employment for both men and women of Charlotte. In the early morning hours of June 20, 1934, the 27-year-old structure burned.

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was first located in Charlotte on Gould’s Hill. It soon outgrew that location and relocated on the field now owned by the Calais Rod and Gun Club. It employed young men, ages 18 to 30, for road construction, flood control, and soil conservation projects. Some roads were built for fire prevention on the Moosehorn Refuge and in surrounding towns.

During the depression years Charlotte citizens maintained their farms, worked on the roads through mud time, built roads and bridges, and cleared the winter snow from the roads. They worked in the woods, hunted bear, fox, and porcupine for bounty and live-trapped rabbits for sale. Some worked on the railroad. Wages were meager but all practiced the “waste not, want not” theory. Even flour bags were an asset and were put to many uses in the home.

Olive Holmes Borton describes living in Charlotte during the Depression. Her father had been a successful businessman in Eastport before the crash:

My father declared bankruptcy. He sold his store to Ted Cummings, and we moved to our house in Charlotte. It was shortly before Christmas. We filled the camp cracks with strips of wet newspaper. An oil drum was converted into a wood-burning stove — it took large pieces of wood. We bought plenty of wood in 8-foot lengths and bought a new “Scout” kitchen stove for cooking. We had an icehouse built to keep meat, etc. fresh; stocked in canned milk, 50 lb. bags of flour and sugar, smaller amounts of corn meal, oatmeal, beans, dry fish, molasses, etc.

Our diet was plain and simple — no extras like today. It consisted of Saturday night baked Navy Pea Beans with hot raised biscuits, warmed over for Sunday. Perhaps on Monday we had dried fish, pork scraps, potatoes and always piccalilli. Tuesday’s menu consisted of fish hash; Wednesday, vegetables and perhaps corn bread. Thursday, chicken, vegetables, gingerbread and Friday, beef stew, etc.

Her brother,Ted Holmes, describes what most today would consider intolerable hardship but felt quite the opposite to Ted and his sister:

My father decided that he could make a living by buying tree lots in the area. He would have the trees cut and sell them for firewood. He had an income of $20 a month from a house which he had sold, and the family would live year-round in the small camp, which was uninsulated, unsheathed on the inside, with no running water, no refrigeration, no electricity and an outhouse for a toilet. There were two wood stoves, a black iron range for both heat and cooking in the small kitchen and a barrel-shaped metal stove created from an oil drum, for heat in the living room. There were two rooms downstairs, living room and kitchen, and two bedrooms upstairs.

One would think that life at the camp was a series of extreme hardships but even today my sister, Olive, says that the time was the happiest part of her life. Recreation was simple. There was no television, no telephone and no radio—only an occasional magazine or newspaper, usually a few weeks old. We had a small phonograph which had to be cranked by hand, and a few records like: “When the Moon Comes Over the Mountain” sung by Kate Smith or “When It’s Springtime In The Rockies.” Sometimes on calm sunny days in the summer, my sisters would take the phonograph out in the leaky, wooden, flat-bottomed rowboat and play the records over and over again. Strains of pleasant music would drift across the quiet lake. There was always swimming or jumping from the barn beams into the hay mow at Bill Bowen’s; picking wild berries or fishing, getting drinking water from the well, and walking or rowing a mile or so to a farmhouse to get fresh milk. Sometimes Clyde Bowen, the woodsman’s son, and I would race old Model T automobile tires by using a short stick. With a quick whipping motion, we would roll and push the tires ahead of us as fast as we could go around the Bowen farmyard or along the dirt country road.

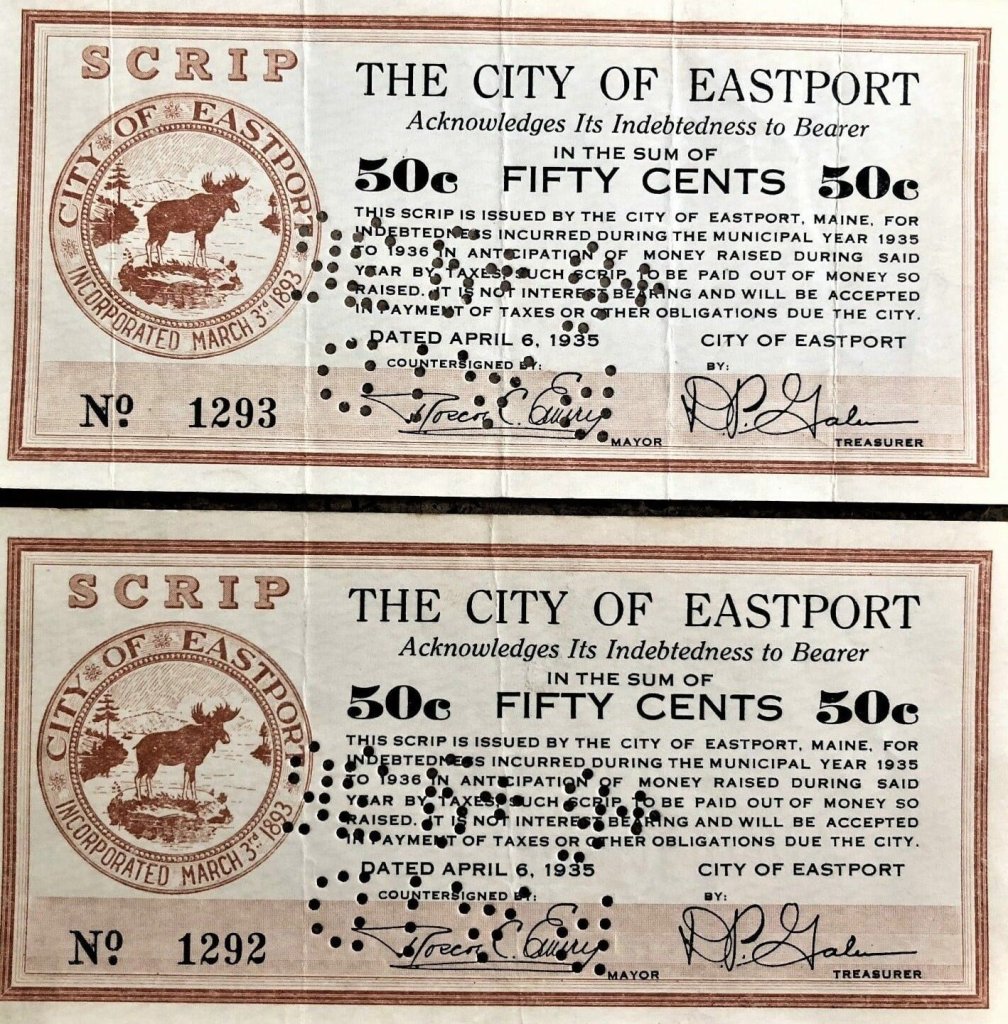

The Eastport Bank also issued currency

The City also attempted to raise money with ‘Eastport Scrip”

Ted and Olive Holmes moved to Charlotte from Eastport after the failure of their father’s store. Times were indeed tough in Eastport. The National Bank of Eastport was also issuing currency in an attempt to stimulate the economy but like Calais it was having little effect. The city was broke as citizens could not afford to pay their taxes. The City sought to raise revenue by issuing its own scrip but how successful this may have been we can’t say.

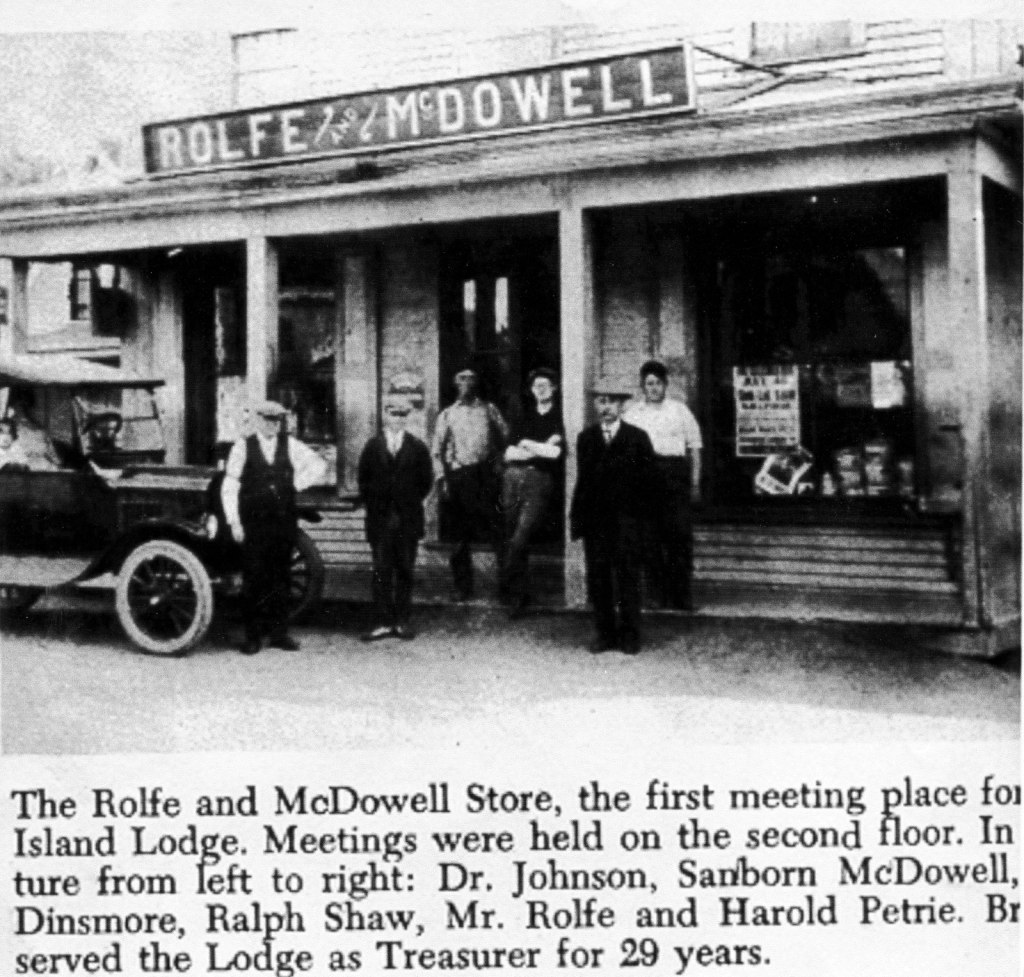

This may have been the store mentioned in the article but we can’t be sure

In Princeton one business which survived was McDowell’s Store. According to Bernard McDowell the business was saved by the frugality of his mother.

In the spring of 1931, my father opened the I.G.A. grocery store in Princeton. This was during the “Great Depression” and money was scarce. At that time, there were six grocery stores in town. Most of the men had work, but because wages were so low, few could earn enough to support their families. This resulted in the stores offering weekly credit, which worked out quite well except when the customer couldn’t pay his bill in full and the balance eventually reached the point where the storekeeper had to say “no more.” The customer then went to another store and repeated the process.

In 1933 the banks were all closed. If you had money in a savings or checking account you were out of luck as you couldn’t use it. At this time, my mother saved our business from closing. Without my father’s knowledge, she had been taking $10.00 from the store receipts each week and stashing it in an old black purse. When this emergency hit, she proudly produced over $900.00 which kept us going until the banks re-opened.

Princeton was luckier than most local towns during the Depression as, like Charlotte, it hosted a large CCC camp. Men 18-25 were given work repairing roads, fire lookout towers and doing other public works projects.

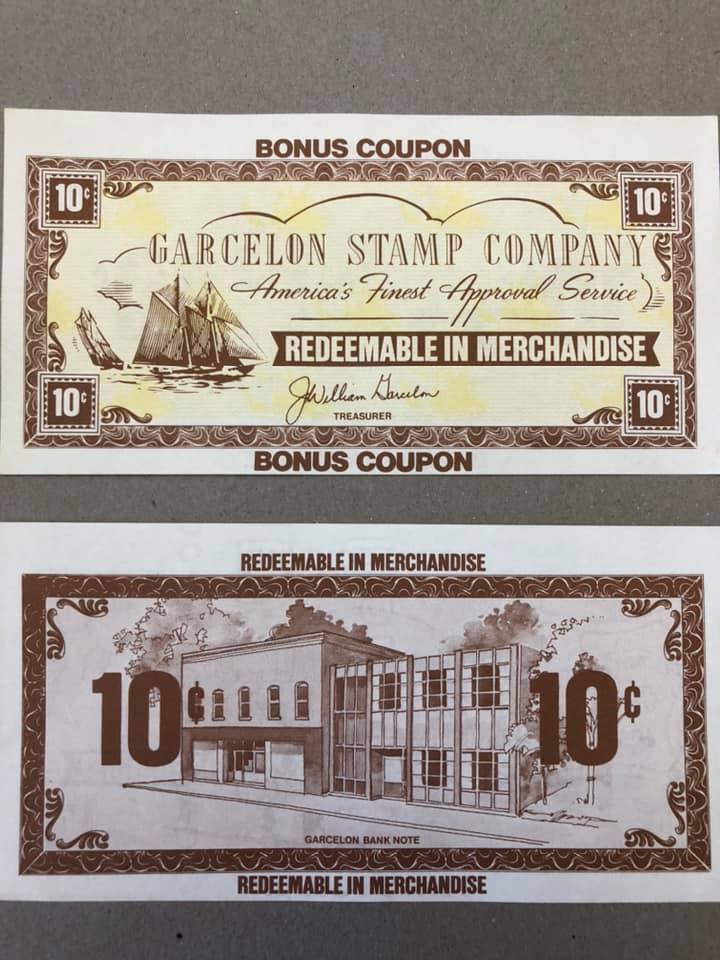

St. Stephen also suffered during the Depression, businesses closed, and many lost their jobs. One of those was Ralph Garcelon whose job as a bookkeeper was lost when the business closed. Garcelon was a stamp collector who had bought stamps through a “stamp approval” operation which sent a collector stamps through the mail for their examination in hopes they would buy. In 1932 Garcelon decided he had nothing to lose by going into the business himself and as the market was in the United States he used the Calais Post Office as his mailing address. Within a couple of years, he had several employees and by 1950 a staff of 60; 750,000 pieces of mail were arriving yearly at the Calais Post Office. This necessitated several trips a day across the border to get the mail. Ralph Garcelon was one of the few people in the St. Croix Valley to come out of the Depression better off than before the crash.

Rum Row, the bridge is at bottom right

The depths of the Great Depression coincided with another epochal event which had an oversized impact on the St. Croix Valley-the repeal of Prohibition. The repeal had an economic impact on the local economy not seen in most communities. Smuggling booze across the porous border from St. Stephen to Calais had been an important source of income to many in Calais, especially those living in the “Union” which bordered the St. Croix River. Many who depended on smuggling also ran speakeasies and they now had to run legitimate businesses and naturally turned to the selling of alcohol legally. Officially only the sale of beer was allowed but there was no appetite for enforcing prohibition in any form so Main Street from the corner of Union Street to the Ferry Point Bridge became a strip of bars known as “Rum Row”.

When in 1934 the 21st amendment repealed prohibition Calais was not long making up for a century of thirst. Beer halls flourished throughout town not only on Rum Row but one owned by Louis Bernadini on Main Street, just up the street from Rum Row and below the former Boston Shoe Store. On November 4, 1936, Leo Skidds, a local boy chiefly known for stealing cars, slid into a booth at Bernadini’s and put two pints of whiskey, still illegal in Maine, on the table. It was not the first whiskey Leo had been friendly with that day. Waiter Roy Moffitt hustled the drunken, angry Skidds and his whiskey out the back door. Sadly, Skidds was still sober enough to find his way back to the front door and, pushing aside Mrs. Bernardini, who had attempted to block his entrance, resumed his place in the booth. The proprietor, Louis Bernadini approached Skidds and was told “Keep away from me, Louis, if you don’t want a bullet” and all may have been well had Roy Moffitt not chosen this moment to walk by the table. Skidd’s, still bearing a grudge against Moffitt, came up shooting. His revolver misfired twice before patron William Tracy managed to hit Skidd’s gun hand just as the third shot was fired striking Moffitt in the groin, passing through his body and out his back. Moffitt was operated on by Dr. Miner and lived. The authorities carted Skidds off to the county jail in Machias where, not surprisingly, no one would go his bail on the attempted murder charge. You can be sure the temperance folks were saying “I told you so.”

In fact, incidents like that were more typical of the experience of local folks than the rather idyllic description of the Holmes family in Charlotte. Many drank to ease, albeit temporarily, the pain and desperation of their lives during the depression. There were few jobs in Calais as the economy deteriorated. Louis Morrison, whose relatives were notorious rum runners from the Union found it hard to make an honest living. Coal was still the main source of heat in the 30’s and huge coal carriers docked regularly at the coal wharf in back of what is now the Heritage Center. Groups of men would greet waiting ship desperate for work to bid on unloading the coal. Most were turned away.

Desperation was the mood of the times for many:

St Croix Courier 1933

Sad Case in Calais Court

At the Calais Police Court Monday a woman was before Judge St. Clair for stealing coal. The case was a sad one, the woman and her children were suffering from the cold with no fuel in the house.

Her husband is not working and she was compelled to get fuel some place, hence the case. She was fined ten dollars and six dollars costs. Two small boys were also given in charge for stealing from one of the department stores. They were allowed to go after a severe lecture from the judge.

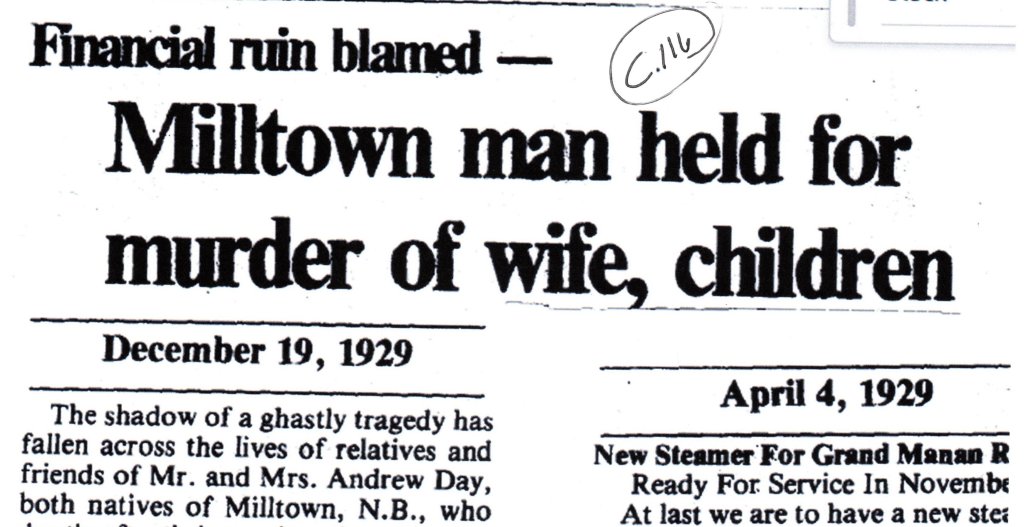

There was one Depression story involving local residents which is so disturbing I am including only the headline. Andrew Day murdered his wife and seven children in December 1929. Both were from prominent Milltown N.B. families and were then living in Three Rivers, Que. He had lost everything in the stock market crash a month earlier. Those wanting more information about the murders can easily find them on Wikipedia although I warn you will find the details very disturbing. It is fair to say that of all the suicides, murders and crimes that can be traced directly to the Crash of 1929, none is more shocking.

While I am only 77, a youngster born 12 years after the great crash, I was not unaffected by the Depression. According to family lore my great grandfather, Sunny Jim Alexander is said to have deposited all of his money in the bank the day before the crash. I find this hard to believe as Sunny Jim rarely had any cash. An entrepreneur of some dubious repute-he had the first gas pump in Calais when there were potential fortunes to be made in selling both cars and gas- Sunny Jim lacked the discipline to stick with anything, even a good thing. Therefore, my grandmother and my mother who was born in 1926, lived on a very skimpy budget, sometimes no budget at all even before the Depression. The Depression and rationing during World War 2 formed my mother’s character and I’m sure the character of many of her generation, the chief characteristic of which was an uncompromising frugality. Even in her later life when she was financially comfortable, she watched every penny. The kitchen table was often covered with coupons and the IGA sales flyer memorized. Sales items were bought in large quantities and stashed for the next Depression in two large freezers and miles of shelves. Cashiers at the IGA often took unscheduled breaks when they saw my mother coming clutching a fistful of coupons. When she died her estate included canned and frozen goods over a decade old which we discarded with regret knowing she would have said they were perfectly good. As a child of the Depression, she never wasted food and she refused to invest any of her retirement funds in the stock market even though I explained to her that the rate of inflation was substantially higher than the interest she was earning in the bank and her wealth was therefore decreasing every year. Still, she trusted the bank only slightly more than the stock market. The great irony is that she was extremely intelligent, well read and sensible but the lessons of the Depression were too ingrained in her to be unlearned. History may yet prove her wise.

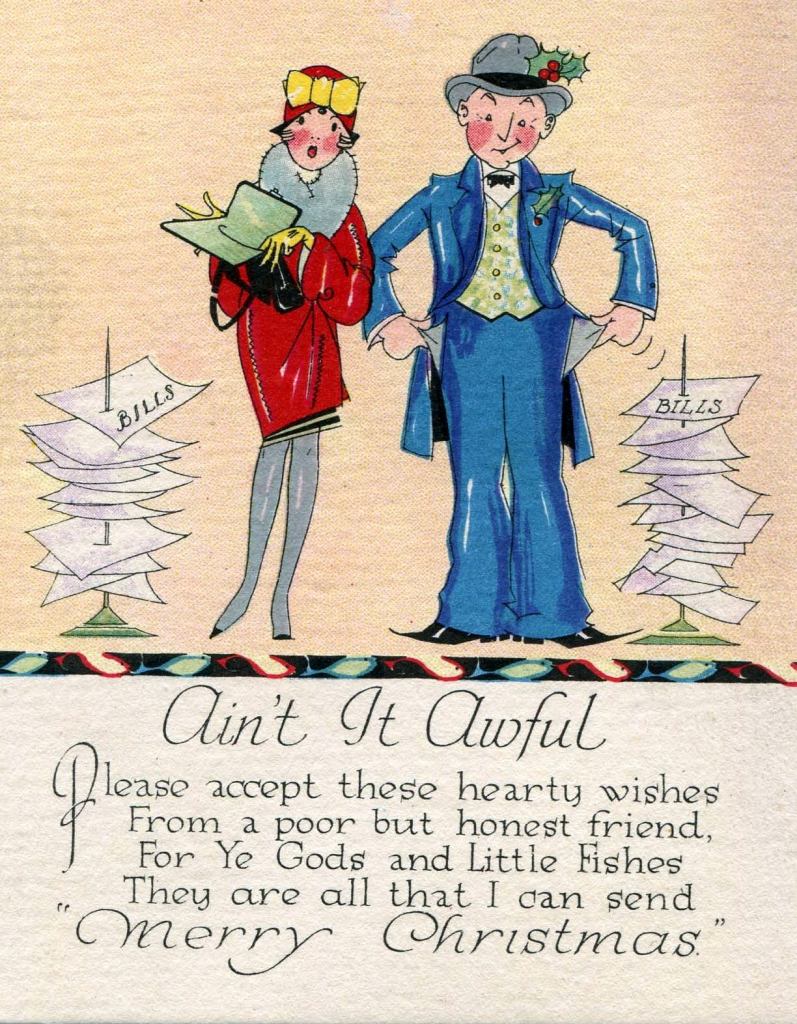

One art which flourished in the Depression was gallows humor.