Machias Courthouse built about 1850, there is no image of the original courthouse built about 1800

In 1798 the Massachusetts Court of General Sessions authorized a committee to build a courthouse for Washington County in Machias. While not yet the official county seat it was the oldest community Downeast and was generally considered by those who mattered in Massachusetts to be the most settled and organized community on a frontier the borders of which were still in dispute with England. As early as 1791 the legal business of Washington County was conducted in Machias and many of the original records of those proceedings, including criminal matters, remain in Machias courthouse. Some years ago, a great deal of work was done to preserve these records, and a list and brief summary of the documents can be found in the Washington County Courthouse Archives.

The Pillory

A review of this summary provides an interesting insight into the type of conduct considered harmful or simply offensive to the public order in those early years Downeast. Naturally assault, theft, murder, etc. and other offenses against the person were prosecuted vigorously by the authorities but these sorts of crimes were rare Downeast in the early days. The first murder in this area was that of Calais Deputy John Downes by the Robbinston counterfeiter Ebenezer Ball in 1811 which has spawned numerous articles and critiques over the years. Ball did not deny he had shot Deputy Downes, but he was probably guilty only of manslaughter, an offense for which he would have been sentenced to only 4 years in prison rather than be remembered as the first person hanged in the District of Maine.

In fact, most of the early “crimes “memorialized in the Machias records are not crimes at all today. In the late 1700’s and early 1800’s nearly all of those who found themselves before the court had committed acts which offended the religious principles of the Puritans. Failure to attend church could result in a fine or even incarceration and in the very early days the authorities could sentence an offender to a period of public humiliation in the pillory in addition to a fine and jail sentence. We can’t say there was a pillory in Machias, but Saint John had a pillory at the bottom of King Street.

Among the crimes cited in the Machias records in the early 1800’s are Disturbing the Sabbath, Disturbing Public Worship and Breaking the Sabbath. One could “Break the Sabbath” even had they gone to church but were seen working in their fields after church or been observed splitting wood to keep warm on a Sunday evening.

Typical is the 1804 indictment against John Leighton-

July 14 – Indictment and Warrant for John Leighton, Yeoman, Twp No.2 – “did on 20th of September, last past, it being the Lord’s Day, labor or work…

Further “church” in those early years was not a Sunday morning affair followed by an afternoon of football. Richard Hayden in his Robbinston diaries which begin in the early 1820’s describes all day sessions of church sometimes ending only late in the evening. In the winter it was often bitterly cold as nearly all churches were unheated, and it took a hardy soul to spend the entire day in an unheated church. Most toughed it out. The eminent historian Ned Lamb relates this story about a stove and the Milltown Maine Adventist Church:

One summer an agent came down from Boston selling heating stoves. Some well-to-do folks bought some, and it was suggested that a stove should be purchased for the little church. At once there was a division. Some wanted the stove, and some did not want any “new-fangle” thing in the church, and any minister ought to preach Hell-fire hard enough to keep himself and his audience warm. It was very close, and one vote brought the stove. It was late in the fall when the stoves came by schooner, and it was a little time before it could be set -up, but at last it was ready and about everyone in the little settlement wanted to see how it worked. The fall day was cold but soon the room got so warm that the preacher took his coat off and then some of the men took their outside coats off, but the women would not stand up to do that, so they fast threw theirs back. Soon some of the men were in shirt sleeves. Then a woman fainted. That broke up the service. She was carried outside, and other women fanned her and brought her around.

The men went into the church and held an indignation meeting and some wanted to get rid of that ungodly thing at once, and of course the agent must pay the money back. There was one good brother who had not said anything, but when the argument was very hot he got to his feet and quietly said. “Brethren, if you -will look in that stove you will see THAT THEM HAS NOT BEEN A FIRE IN IT SINCE IT WAS MADE.

The prosecution of those who failed to observe the Sabbath did not endure very long into the 1800’s and even Robbinston’s Richard Hayden, a devoutly religious man, soon began skipping church himself some Sundays and casually remarked in a later entry that his son had ceased going to meeting altogether.

The first criminal offenses reported in the Courthouse records are from the year 1791 and constituted what we would consider today immoral, not criminal conduct. All the charges were for “Fornication-Bastardy” and those charged are all women. They were fined 6 shillings. In fact, most of the reported cases in the early 1800’s were similar and it is possible they were an attempt to establish paternity and hold the father responsible to support the child.

After the 1820’s the Courthouse records began to report more of the sorts of criminal offenses we would recognize today such assaults, larceny, theft etc. However, there are also many charges which we would not recognize today. There was no written criminal code such as today’s Maine Criminal Code, 311 pages which can take a dozen pages to define even simple criminal conduct. Instead, Maine operated under the common law which allowed a good deal of flexibility in fashioning offenses which fit a particular situation. For instance a person could be charged with leading an idle and vicious life, falling into habits of vice and immorality, being a railer or a brawler or nightwalking. This last offense was always applied to women who couldn’t give an adequate explanation for being away from home after dark.

Swearing and using wanton and lascivious speech was also a crime and if the authorities simply didn’t want you in town you were charged with being a tramp and you could be hustled out of town before you were imprisoned for debt. The jails were full of debtors in the 1800’s who often found themselves incarcerated for longer than violent criminals because no one would pay not only the money the debtor owed but the daily increasing room and board charges at the jail.

Another popular charge in the 1800’s was “riot” which was defined as five or more people engaged in disorderly conduct. This usually appears to have involved the destruction of substantial property or several injuries in a liquor fueled brawl:

1836 – Mittimus, Oliver Smith – Riot in Calais, July Fourth – “did take …one barrel filled with rum, one keg filled with brandy, one jug filled with gin, and one keg filled with spirituous liqueurs… spilled and destroyed …in the custody of John C. Dutch…”

Overall, however, crime Downeast during the first half of the 19th century does not appear from the Courthouse records to have been a serious problem. Murders, sexual assault and crimes of violence other than simple assaults did occur but infrequently. In fact, in 1850 when Maine had a population of 580,000, half of today, the Maine State Prison reported 73 inmates. 48 were incarcerated for larceny, five for manslaughter and three for murder. There were two inmates convicted of rape, seven convicted of assault with intent to ravish and a few burglars, forgers and three adulterers. This compares with a state prison population of about 1000 today. Crime, however, was very soon to become a much greater problem in the State of Maine.

Neal Dow, Mayor of Portland and Temperance Advocate

A year later, in 1851, the State of Maine became the first state in the Union to enact a law banning the sale of alcohol. Encouraged by Neal Dow, the Mayor of Portland, a Quaker and leader of the Maine temperance movement, the State banned the sale of all liquor except for “medicinal, mechanical or manufacturing purposes.” Deeply religious, Dow was also anti-immigrant and especially anti-Irish who he believed responsible for what he perceived to be the sinful behavior of Portland citizens. When it was reported, truthfully, that there was $1600 worth of liquor stored in the basement of City Hall in violation of the law the citizens rioted, stormed City Hall and broke many of the bottles of liquor. Dow ordered the militia to fire on the protesters. The incident became known as the “Portland Rum Riot” and it finished Dow’s political career. Within months he was voted out of office and the Maine law, while initially lauded as a momentous legislative success, soon became very unpopular. Enforcement was nearly impossible, especially Downeast.

A poem written by a local wag

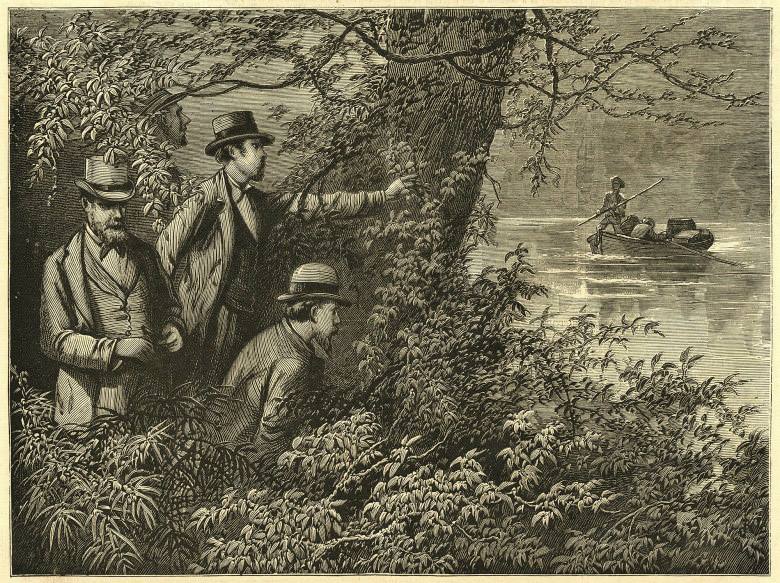

Revenue agents at work. From an 1873 magazine article on smuggling on the St. Croix

The hope that Maine’s law would somehow dissuade its citizens from drinking was in vain. It soon became apparent that the only way to make the law work was strict enforcement and this required legions of lawmen, border controls to keep liquor out of Maine and courts willing to lock up ordinary citizens in the thousands. None of these requirements were met. Downeast had hundreds of miles of seacoast bordering on a “wet” New Brunswick and hundreds of miles of land border with two large Canadian provinces. Downeasters also had a rich history and tradition of ignoring revenue and customs laws. The law did, however, have serious practical consequences because the temperance folks had sufficient political power to force the authorities to act against the “rum sellers”. Alcohol consumption only decreased marginally if it decreased at all. Further home brew often contained chemicals which were hazardous to the drinkers health Crime associated with the new law abounded with liquor violations exceeding nearly all other offenses- disorderly houses and tippling shops were raided, citations for being drunk and intoxicated filled Court dockets and law enforcement was under constant pressure to arrest the rum sellers who were, in many cases, the fellows they drank with on the weekends.

The most deleterious effect of the law was on the social fabric of the community. Disagreements within families and among friends were common and sometimes bitter. The Bangor Whig and Courier reported that when the respected and beloved Dr. Oliver Wendall Holmes Sr, denounced Maine’s liquor law as a “remnant of Puritan intolerance and fanaticism” he was hissed by the pro-temperance crowd. Crowds of temperance supporters engaged in vigilante action against suspected rum shops but as the years went by most came to agree with remarks made in 1899 the widely respected Rev George Degen of St. Mark’s Church in Augusta:

Take the Maine liquor law for instance, probably the worst piece of legislation ever devised for the control of the liquor traffic. Everybody knows that it is an utter farce, a farce by not too pleasant a name to give to anything so dreadful. Everyone knows that it is the flimsiest kind of pretense which while it directly fosters drunkenness, at the same time educates our youth in utter contempt for the majesty of the law and leads them to regard all moral teachings as a sham. Whoever attempts to get this monstrous inequity expunged from our statute book must encounter the combined political machinery of both parties, for neither party will declare against it lest they should lose votes. He must expect to see a raid against him, the respectable classes on the one hand who piously pretend that they believe in it, lest they should be thought to favor intemperance; and on the other the influence of the liquor dealers, because they know that it is for their interest to have the law remain as it is.

1846 painting showing a husband signing a “pledge” to stop drinking

The temperance folks remained more vocal in their support of the liquor law than those who wanted it repealed. Reverend Degen and Oliver Wendell Holmes were in the minority in their vocal support of repealing the law but Downeasters were definitely tiring of raids, search warrants, arrests and general discontent occasioned by the enforcement of the Maine Liquor Law. Even the local press began treating the whole business as rather a joke. Consider this 1883 article in the Calais Times which first discussed the case of a couple of swindlers in Eastport and a horse killed in a collision on Water Street and went on to write:

All of these things excited us and kept us talking till January when a long-expected raid was made upon the worst of all criminals in our state, the rum sellers, by the sheriff of the county, who I believe, resides somewhere in the suburbs of the city of Calais. This caused much excitement with its arrests, officers, counsels, magistrates, County Attorney, continuances, anonymous letters, summonsing of witnesses, mysterious trips to Calais, doubt about convictions, delays, summonings of more witnesses, mysterious trips to Calais, doubt about convictions, delays, summonsing of more witnesses, charges of forgery, charges of perjury, charges of bribery and other pleasantries of a similar nature which were indulged in by the accused, counsel, witnesses, officers and outsiders for more than two weeks.

One troublesome individual, gloating over the turmoil, and not content to see his own town laboring under this load, but wishing to injure the good city of Calais, did falsely, unlawfully, wickedly and maliciously set abroad, undertake, essay, strive, try and attempt to injure and destroy the good name, fame and reputation of his own town, and also the good name, fame and reputation of the City of Calais, by falsely, unlawfully, wickedly, knowingly, with malice aforethought, charge through the Bangor commercial that there are 25 rum sellers in Eastport and 30 more in Calais, the Times with that promptness which characterizes the newspaper devoted to the welfare of the good name of its own town, corrected the error and rebuked the slanderer. I am now authorized to state that there are only 5 rum sellers in Calais, in fact the authorities don’t know of any, and two in Eastport.

Temperance advocates were angry at the lack of enforcement and protested to local politicians

Local temperance groups demanded hearings on the failure of local communities to enforce the liquor law and although they generally carried the day at these hearings enforcement efforts were always short-lived. Raids would increase for a week or two, but the trade would soon be back to normal. The law was simply unenforceable.

Clergymen and politicians from all over the world were assured by the Maine Temperance League that the law was a great success and came to visit Maine to report back to their communities. They usually left disappointed. In 1900 the Bangor Commercial reported on a visit of Dr. Gamble of New Jersey:

Commercial reporters were unable to discover on Friday that Doctor Gamble had commenced his investigations in Bangor as yet. At the Bangor house the clerks announced that the name sounded familiar but a scrutiny of the register failed to reveal the fact of his presence during the past week. His shirt has not been seen either.

Doctor Gamble will be by no means the first person who has visited Bangor for the purpose of studying the prohibitory law. It was only eight or nine years ago that a committee from the Canadian parliament visited Bangor and remained here a week collecting data in relation to the subject. Before visiting Maine, they had been listening to the claims of certain temperance bodies who said that the law was enforced to the letter and they were prepared to find a community entirely devoid of saloons and bars. It took several minutes to discover this mistake. The remainder of the week was spent in recovering from the shock.

A Parliamentarian from England came for the same purpose. He checked into a local hotel without divulging his nationality or purpose and asked the clerk where he could get a drink. Within an hour he was bellied up to a local bar and, we assume, reported to our cousins across the sea that the law was a complete failure.

Enforcement of the liquor law became increasingly unpopular

The Boundary House in Milltown, just above Knight’s Corner

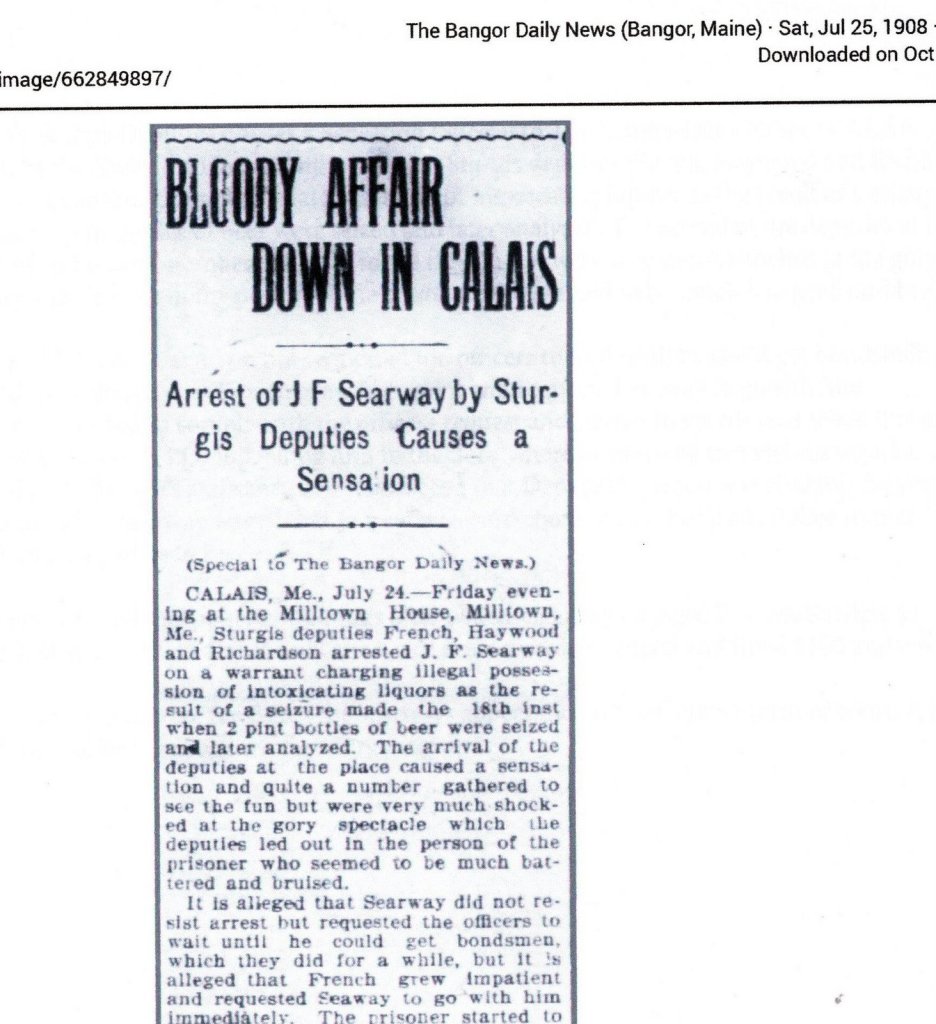

By 1900 the Courthouse records seem to show a distinct decline in the enforcement of the liquor law. State revenue officers who were known as “Sturgis men” were increasingly unwelcome in major cities and told to stay away. Perhaps this Calais incident explains the reason for their unpopularity.

Arrest of J. F. Searway by Sturgis Deputies Causes a Sensation (Special to The Bangor Daily News.) CALAIS, Me., July 24. Friday evening at the Milltown House, Milltown, Me.,

Sturgis deputies French, Haywood and Richardson arrested J. F. Searway on a warrant charging illegal possession of intoxicating liquors as the result of a seizure made the 18th inst when 2-pint bottles of beer were seized and later analyzed. The arrival of the deputies at the place caused a sensation and quite a number gathered to see the fun but were very much shocked at the gory spectacle which the deputies led out in the person of the prisoner who seemed to be much battered and bruised.

It Is alleged that Searway did not resist arrest but requested the officers to wait until he could get bondsmen, which they did for a while, but it is alleged that French grew impatient and requested Seaway to go with him immediately. The prisoner started to comply with the officer’s request and started to get his coat when it is alleged French struck him on the head with his club felling him to the floor where he received two vicious whacks. The other two deputies rushed to French’s assistance, and it is alleged that Deputy Haywood was choking the prisoner while he was being handcuffed.

Searway was placed in a carriage and conveyed to the Calais Police station bleeding freely from two ugly gashes in his head.

Dr. L. Brehaut was called and dressed the prisoners’ wounds after which Searway engaged R. J. McGarrigle as counsel. Recorded Beckett was notified and shortly afterward Searway was arraigned and fined $100 and costs. Counsel appealed and $200 bonds were furnished for Searway’s appearance at the October term of court. It is probable that legal action will be taken against the Sturgis deputies.

The Calais Times rose to Searway’s defense, reporting the incident in even more graphic and violent fashion:

When first struck he was reaching for his coat, being then in his shirt sleeves, to put on to accompany the officers, he says and was rendered unconscious, and did not know how many times he was hit. Be the circumstances what they may, it seems as if two powerful men Messrs. French and Hayward should have been able to have secured the prisoner with less bloodshed than was in evidence on this occasion. Whatever may have been his career in Bangor, since his residence in Calais Mr. Searway has been without reproach. He opened an intelligence office at Ferry Point about two years ago, and some months ago purchased the old boundary house in Milltown, which he has since conducted as a boarding house, largely for cotton mill hands, in a matter satisfactory to the neighborhood and to the authorities.

George Magoon Crawford, center

As noted above, by the late 1800’s everyone except very hardcore temperance folks were disenchanted with liquor law. Although the courthouse records show a decline in “liquor” cases the authorities found themselves very busy enforcing the new fish and game laws which for the first time put strict limits on the amount of game a hunter could take and further limited the season during which hunting was allowed. If anything, these laws changed Downeast even more than the liquor laws and created an entirely new class of offender- the fish and game felon. The Days of Wesley, the Hatts and Magoons of Crawford and dozens of others fought a fierce battle with the Maine’s game wardens in what became known as the Downeast Game Wars. Several Wesley men spent considerable time in prison for burning a game warden’s barn.

A lot was at stake. Until the late 1880’s local men were able to feed their families and make a living on the side by taking game. What they couldn’t eat they could sell to lumber camps in the winter or ship in barrels by sea to Boston where venison was a popular menu item in upscale restaurants. When the railroad made Downeast easily accessible to the well heeled in Boston, New York and Philadelphia the area was “discovered” so to speak and large resorts like the Algonquin were built. “Sports” began to arrive in the hundreds in places like Grand Lake Stream hoping to take home a trophy for the den. A deer worth a few dollars to a local hunter was worth a hundred to a local camp owner or guide in Princeton because sports were willing to pay handsomely to shoot it or have it shot by the guide and claim credit. The “Sporting Camp” industry became a big business which could not flourish if Wilber Day, George Magoon and their friends shot dozens of deer every year. Hence the game limits and the declaration of war against the new game laws by the local hunters.

The Courthouse archives contain many references to the transgressions of Wilber Day, George Magoon and the other combatants in the game wars. File 4702 of the Courthouse records contains the documents related to Day’s arson conviction. It may also contain a copy of the song Day wrote while serving his sentence with which I’ll end this already overlong article.