Trumbull’s iconic painting of the signing of the Declaration of Independence July 4, 1776

Perhaps the most famous painting in our history is John Trumbull’s painting of the delegates to the Continental Congress signing the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. Whether it depicts the actual signing or the presentation of the document to Congress is unclear, but it is known to be a composite painted over several years which omitted several of the signers because Trumbull could locate neither the signer nor a likeness for the painting. One such omission was Matthew Thornton, a delegate from New Hampshire who was the last signer of this famous document, appending his signature on November 4, 1776, exactly four months after the actual signing. By then the British had already occupied New York and hanged Nathan Hale.

The reason for Matthew Thornton’s delay in signing the document is not entirely clear and even the true identity of the signer has been disputed both in the newspapers and within the Thornton family. In 1776 there were two Matthew Thorntons living in New Hampshire, the elder Matthew Thornton in Londonderry and his nephew on the family estate at Thornton’s Ferry about 16 miles to the west. While the elder Thornton was a successful attorney, judge and politician, the younger was a successful businessman and, at the time, a well-respected citizen of the state. Either could conceivably have been a delegate for New Hampshire to the Continental Congress although the elder Thornton was certainly the more likely choice for such a prestigious position and it is the uncle who is honored in New Hampshire- schools and other buildings have been named in his honor, monuments erected, and celebrations held to honor his role in the founding of our nation.

Over the years, however, questions have arisen about the true identity of the Matthew Thornton who signed the Declaration of Independence, and some have contended with the support of members of the family that Matthew Thornton the nephew was the actual signer of the Declaration of Independence. This brings the controversy home to the St. Croix Valley because Matthew Thornton the younger is buried in Dufferin, just outside of St. Stephen.

One of several article questioning the identity of the MatthewThornton, last signer of the Declaration of Independence

Kennebec Journal November,12 1898

AN HISTORIC PICTURE

One Taken of the Grave of a Revolutionary Statesman

A Remarkable Coincidence Connected with Another Photograph-Rice and Glue

Chester H Messer of this city has a picture taken by himself in a New Brunswick town in 1897 that he values highly, as it is one with which there is a history connected. This history is of a man who was one of those who signed the Declaration of Independence and who afterward turned to become a confirmed English sympathizer. The picture is of the place in Dufferin N B where the remains of the traitor now lie and the place where he fled after escaping from the hands of the Americans during the Revolutionary War.

Matthew Thornton was the man’s name. He lived In New Hampshire, and he was the third to sign the famous Declaration of Independence. He became an English sympathizer soon after and was placed in prison from which he escaped and went to Dufferin. While there he lost his family and home by the hands of the redskins one day, while he was away. When he returned home that night his family were all slain and the house in ashes. He found but one thing that had formerly belonged to him and that was his family Bible and his Masonic jewel which was in the Bible.

He died later and was buried in this town. The churchyard is a desolate place as shown by the picture in Mr. Messer’s possession.

Many are probably unfamiliar with Dufferin. It is on the St. Croix between St. Stephen and the Ledge and 200 years ago was home to many Loyalists who had fled those rude and undisciplined rabble, otherwise known as patriots, who had inconceivably defeated the mighty armies of King George and gained their independence from England. How a signer of the Declaration of Independence could have become a Loyalist living in Dufferin is an interesting story.

The article above was one of many which appeared in newspapers over the years. In 1892 the Lewiston Sun-Journal wrote:

It is not generally known that the grave of Matthew Thornton, the third signer of the Declaration of Independence, is at the ledge near Calais, Me. The story is told by some of his ancestors who live in that city that after signing the Declaration he repented and again he became an English sympathizer, after which he was arrested and put in prison. They say that while in prison it was discovered that he wore a Free Mason’s pin and through its influence he was given a certain amount of time to get to English soil. He settled on the east side of the St. Croix River, built a house and cleared a farm.

At one time his house was destroyed by Indians and the only thing saved was a large Bible, which escaped the fire by being thrown into a brook. The Bible and Masonic pin are in the possession of one of his descendants now living in Calais.

To be honest the above accounts seem questionable. The claim in both stories that Thornton’s home had been destroyed by Indians was certainly untrue as the Passamaquoddies always lived in peace with white settlers in the St. Croix Valley and there is no instance of them attacking any white settlement or home. Further Matthew Thornton was the last not the third signer of the document. Nonetheless it seems there is a case for both Dufferin and Merrimack, New Hampshire where Matthew Thornton the Elder is buried and I decided to look into the respective claims.

I thought it wise to visit the cemetery in Dufferin. This presented a problem as I knew only the general location of the settlement and had no idea where the cemetery might be. Thankfully Darren McCabe, who is our expert on all things local across the line was able to not only take me to the cemetery but also establish that Matthew Thornton was buried there. Unfortunately, the 1898 description of the cemetery as a “desolate place” is even more accurate 125 years later. The foundation of the old church which stood in front of the cemetery remains visible but the stones and markers in the cemetery itself are broken, mostly illegible and more often than not buried under two centuries of tree fall and decomposed vegetation. Our search for a Thornton marker was in vain although we do know from historical records he is buried there.

The Case for Dufferin

As noted above the “Dufferin” claim has long been the subject of newspaper articles in national and local papers. The St. Croix Courier in July of 1892 published one such article although it also expressed some doubt as to the veracity of the story:

A representative of the ‘Courier’, however, who investigated the report some six months ago before it appeared in print, found reason to doubt that he and the Matthew Thornton who signed the Declaration were the same, as the history of the latter is well known and his burial place pointed out elsewhere.

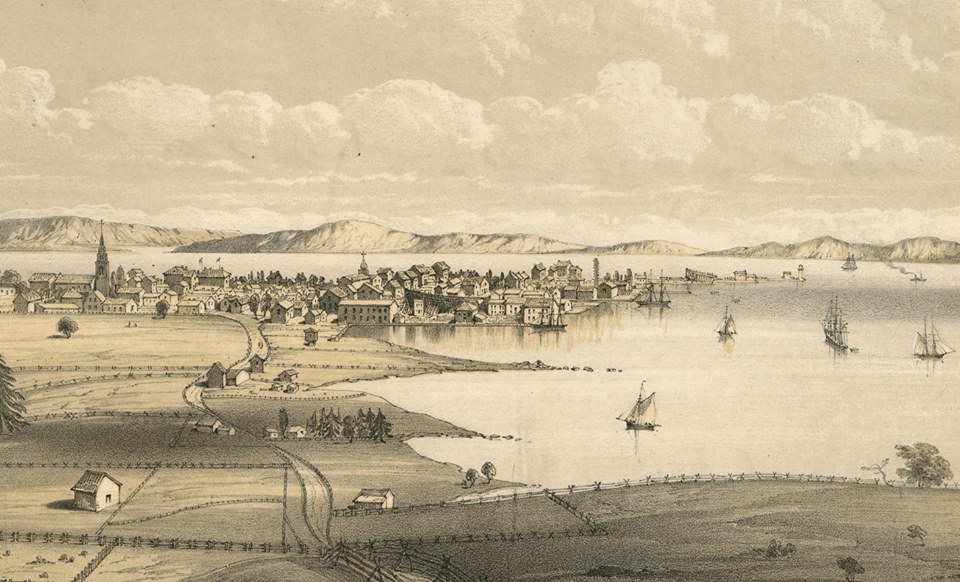

Early sketch of St. Andrews. Thornton first settled just above the town. (Tides Institute & Museum of Art collection)

The controversy was much debated locally into the early 1900’s. A paper read before the Canadian Literary Club of St. Andrews in 1907 supported the Dufferin claim but other local historians including the noted St. Stephen historian James Vroom was less sure. In the late 1800’s Vroom thoroughly investigated the Dufferin claim. He interviewed family members of Dufferin’s Matthew Thornton, collected documents and checked the historical records. Guy Murchie in his 1947 book “St Croix” reports Vroom’s findings:

There is a story connected with the coming of the Loyalists to St. Andrews which it may be of interest to record in closing this chapter of early life in the parent town of the St. Croix, eldest in point of settlement, and leader for a long period in its trade and shipping. Matthew Thornton, a member of the Penobscot Association, had a town lot in 1784 at St. Andrews and a farm on the river between the Ledge and the Narrows. Later he sold his farm and settled near Pagan’s Cove in Oak Bay. There he died in 1824. He was apparently a tight-lipped man and the public knew nothing of his past. Yet he must have talked within his family. When he died it was said that he was a signer of the Declaration of Independence. It would be natural, if he was signer, to avoid mention in Canada of such an unpopular fact about himself.

About fifty years ago James Vroom, painstaking and important historian of Charlotte County, who contributed much local history to the St. Croix Courier, a weekly journal published in St. Stephen, became interested in the Matthew Thornton story. He found that there were two Matthew Thorntons, uncle and nephew, who lived in New Hampshire before the Revolution. The uncle was a doctor in Londonderry and was well known by that title. As surgeon in the Shirley expedition against Cape Breton, he was present at the surrender of Louisburg in 1745. Although he held a commission under the Royal government, he joined the revolutionary party and was president of a Provincial Convention held at Exeter in 1775. He was a well-known man and may have been the Matthew Thornton who affixed that name to the immortal document. In the Journal of the Congress of 1776 a Matthew Thornton is mentioned as a delegate from New Hampshire without the title of Doctor. At that time the nephew was eligible to have been such a delegate. Whoever was the signer, his is the last signature to the Declaration.

Matthew Thornton, the nephew, born in New Hampshire in December 1746, lived on the family place at Thornton’s Ferry. According to family tradition, he was active in the revolutionary cause and was a captain of a company of insurgent Americans. Two of his brothers-in- law named Crawford served under him. His company having been mustered out, he went as a civilian in 1777 to look after some property he was interested in near Bennington, Vermont. The British were active in that territory. Thornton fell in with the King’s forces, was taken prisoner and impressed to drive one of their ammunition wagons. While so engaged some patriots saw him who knew him. On his return home he was arrested, accused of treason, tried and finally honorably acquitted. But suspicions and threats followed. Being a freemason, he was aided by brother masons in leaving the country and came by boat to St. Andrews, passing the winter alone with his dog on St. Andrews Island. He applied for and received a grant as a member of the Penobscot Association. James Vroom obtained the following statement from Joseph Donald of Dufferin, member of the New Brunswick House of Assembly, whose wife was a granddaughter of Matthew Thornton, the Loyalist:

“It has always been known in the family that Matthew Thornton of the Penobscot Association was a signer of the Declaration of Independence, though for obvious reasons very little was said about it during his lifetime. As a Loyalist among Loyalists, he would of course prefer that the fact be forgotten, and it would have been more in accordance with his wishes if it had still remained a family secret. Soon after I became acquainted with the family, which was nearly seventy years ago, I first heard it mentioned. This was but a year or two after Matthew Thornton died. His widow was still alive.

“A little incident that convinced me of the truth of this story took place at the house of his son, afterwards my father-in-law, who was also named Matthew Thornton. A friend had sent me a group of portraits of the signers of the Declaration of In-dependence. Showing this to Mr. Thornton without letting him know what it was, I asked him whether he knew any of the faces. He pointed to one and said ‘Why, that’s Father Thornton and showed it to his wife, who also recognized the likeness. Then I told him the pictures were those of the signers of the Declaration of Independence and the one he had pointed out bore his father’s name and he said ‘Yes, he was a signer.’ “

Top signature from the Declaration, the other two from documents signed by Matthew Thornton in Canada

James Vroom went further. He found a document belonging to Nehemiah Marks and witnessed by Matthew Thornton the Loyalist, and also a note of hand given to Aaron Upton in 1813. These signatures and the name signed to the Declaration of Independence are reproduced here.

While the signatures do bear some similarities, they are certainly not conclusive, unless you happen to be a family member who supports the Dufferin side of the argument. In 1976 Jean Irish Weare advanced a rather different argument which admitted that Thornton the Elder was the delegate to the Continental Congress but pressed by the burden of legal practice he dispatched his nephew to Philadelphia to sign the Declaration of Independence for him.

Portland Evening Express November 29, 1976:

Thornton Tale Revived by BRUCE ROBERTS

The Matthew Thornton who signed the Declaration of Independence isn’t the right one, a local woman claims. Mrs. Jean Irish Weare 125 Massachusetts Ave claims that while a Dr Matthew Thornton who was born in Ireland and lived in Londonderry N.H. is credited with being a signer of the Declaration of Independence the actual signer was his nephew of the same name who lived in Thornton NH at the time of the Continental Congress.

Mrs. Weare says that the “fact that junior signed is a family story” which has come down through seven or eight generations She is a direct descendant of the younger Matthew Thornton through his daughter, Leah Thornton, who married an Abiel Sprague of Baileyville Maine. She believes that the “family story” has been vindicated now that she has been able to pull copies of Matthew junior’s signatures from the New Hampshire State Archives to compare with the putative signer Matthew senior. The signatures, though they haven’t been authenticated by an expert, do seem to be by different hands.

The “family story” is further corroborated by historian Guy Murchie whose “Saint Croix: The Sentinel River” which appeared in 1936 notes that “It has always been known in the family that Matthew Thornton of the Penobscot Association (the younger Thornton) was a signer of the Declaration of Independence though for obvious reasons very little was said about it during his lifetime” Mrs. Weare a member of the Daughters of the Revolution who has taken an interest in the family history explains why Matthew junior elected to remain silent about his role in the famous document. Both uncle and nephew were both active in the revolutionary cause and both were eligible to be delegates to the Continental Congress from New Hampshire which could be another cause of the confusion. Matthew junior would have been 29 at that time, his uncle 61. Why the uncle who was nominated to the Congress switched places with his nephew isn’t known but Mrs. Weare speculates that “for some reason he couldn’t go and asked his nephew to go in his place”.

THE CASE FOR NEW HAMPSHIRE

It has to be admitted that the case for New Hampshire is very strong. Monuments have been erected, schools and parks named, and celebrations held in New Hampshire for Matthew Thornton the elder for well over a century.

The second paragraph of this 1776 article confirms the delegate from New Hampshire was from Londonderry

With the help of Newspapers.com I was able to confirm it was the uncle and not the nephew who was appointed as delegate to the Continental Congress. As we know, the uncle was a judge and attorney in Londonderry while the Dufferin nephew lived in Thornton Landing. Further there is local support for New Hampshire’s claim. In the Calais cemetery there is the grave of Annie MacBean Hatton who is a distant relative of, she claims, the Matthew Thornton who signed the Declaration of Independence. Her description of him can apply only to Matthew Thornton the elder, at least as it was related by her during a “Cemetery Tour” performance a few years ago. Admittedly Jerry Lapointe of our historical society wrote the script but only after a good deal of research. She describes her relative and the signer of the Declaration of Independence as “The first president of the New Hampshire House of Representatives and an associate justice of the Supreme Court of New Hampshire” which Dufferin’s Matthew Thornton most certainly was not.

THE VERDICT:

The best Dufferin and the St. Croix Valley could possibly hope for in this case is a hung jury. However, as surprising and interesting it would be to have a signer of the Declaration of Independence buried just across the river in Loyalist territory, we have to concede the historical evidence is strongly against this. Dufferin’s Matthew Thornton was not New Hampshire’s delegate to the Continental Congress nor is it at all likely his uncle delegated his important responsibility of signing the Declaration of Independence to his nephew. The case for Dufferin depends entirely on family history which as anyone who has ever done historical research will confirm is more myth and legend than accurate history. Still the story of Thornton the younger is interesting even though he almost certainly did not sign the Declaration of Independence.

The Loyalist emigration from the Colonies to St. Andrews and St. Stephen after the revolution marked the beginning of the development of the St. Croix Valley. The valley would likely have remained an insignificant backwater for many decades, if not forever, had the Loyalists not settled here. While Thornton was not strictly speaking a Loyalist, he was forced by circumstances to begin a new life on what was then the frontier and still disputed territory. He lived to see his native land and his adopted country go to war again in 1812. From his first home just above St. Andrews he would have seen British warships bombarding Robbinston and perhaps watched the Redcoats storm ashore at Robbinston. [Clarification: see more on the Battle for Robbinston.] He would have heard and perhaps seen them shelling Fort Sullivan in Eastport. How he felt about the war is unknown but as a former patriot who had lived for decades among Loyalists, he surely felt the conflicted allegiances of his youth keenly. It must have been a difficult time for him.