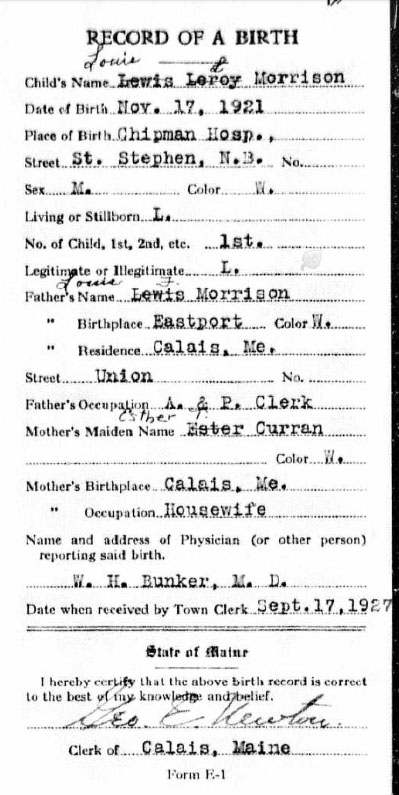

Louis “Louie” Morrison Birth Certificate

Louis Leroy Morrison was born at the Chipman Hospital in St. Stephen on November 17, 1921. The record of his birth was not filed with the Clerk of the City of Calais until six years later and contains several misspellings which were corrected by the simple expedient of crossing out the incorrect entries and handwriting the presumably correct spellings of the names. As a result the name of the baby born to Louis E. Morrison and Esther Morrison nee Curran in 1921 was sometimes spelled Louis or Lewis and pronounced Louie but to avoid confusion the boy was simply called Red by family and friends. Around town he was generally known as Louie.

Louie grew up in the section of Calais known as the Union. Some years ago, we talked with Louie about his early years, and he recounted many interesting stories of the life of a boy growing up in the Union section of Calais in the 1920’s and 1930’s. We’ve recently filled in other parts of his story by talking to his daughter Linda McLaughlin, Class of 1965 and her husband George “Butch” McLaughlin, Woodland Class of 1963.

Life in the Union was tough even in the roaring twenties before the Crash of 1929 and the depression that followed. According to Louie women in the Union worked primarily in the shoe factories or as stitchers in the clothing factories which is how his mother Esther is described in the 1935 U.S. Census. Men were truckmen, laborers or worked on “own account” as his uncle Edward “Eddie” Curran is described in the census which implied they really didn’t have steady work. By the late 1920’s many of the shoe and clothing factories had closed and Louie’s father had left the family to return to his hometown of Eastport. His mother Esther had no choice other than to relocate to where the work was and in 1930 we find Louie and Esther living in Waltham Massachusetts, boarding on Crescent Street with several other lodgers, presumably working in one of Waltham’s many shoe factories. Louie’s only sibling Frank had died at the age of two.

They returned to Calais in the early 30’s and lived with his mother Esther’s brother John Curran and wife Bessie on Union Street. Louie and his friends hung around the waterfront where huge schooners still brought coal to the coal wharf in back of what was recently the Heritage Center. Men from the Union would form gangs and bid with the ship owners on price for unloading the ships, hoping for a couple of days honest work. Sometimes they were underbid by other gangs of workers.

It is fair to say living with John and his ten children at 178 Union Street was never easy but also never boring. John had, as the saying goes, no visible means of support but the family got by just barely thanks to Prohibition. John and John’s brother Edward “Eddie” Curran were notorious bootleggers.

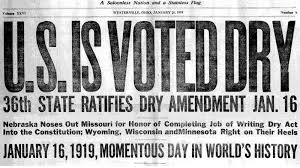

Maine was already dry in 1919 but the Volstead Act made smuggling even more profitable

According to Louie, vessels usually from Belgium would lay about three miles off shore loaded with rum in three gallon steel or tin containers labelled “Hand Brand” because each container had a print of a hand on the side. Fred Spinney who owned a store at the corner of Main and Union and lived in the Union would get word the boat had arrived and he would take his speed boat which he kept in St. Stephen out to the Belgian boat, pay cash and load up with cans of 180 proof Hand Brand rum. These he took back to St. Stephen to a place near the axe factory on Dennis Stream. Louie’s uncle John Curran would take his horse drawn wagon across the bridge and put a half dozen or so cans of Hand Brand in the cart and then go to Haley’s lumber and have them covered with scraps ends of apple boxes or other scrap wood and go back across the bridge to Calais. Louis often accompanied him on these trips. Louis says the Customs Officers knew what was going on but never searched the cart.

While John never drank he supported the family entirely by bootlegging. He also owned a small lot near the St Stephen cemetery and would sometimes meet his Canadian seller there where he would cover the cans with loam before returning to Calais. In emergencies when the supply was low John would load the kids in the backseat of Eddie Curran’s car and put a few cans under the backseat where the kids were sitting confident no customs officer was likely to unload a half dozen Union Street urchins to search under their seat.

Louie said his Uncle John always had a ready supply at his house. His customers would leave with a bottle of “split” which was 180 proof alcohol mixed with water and sugar in a baby bottle. His uncle was only one of many homes on Union Street in the bootlegging business.

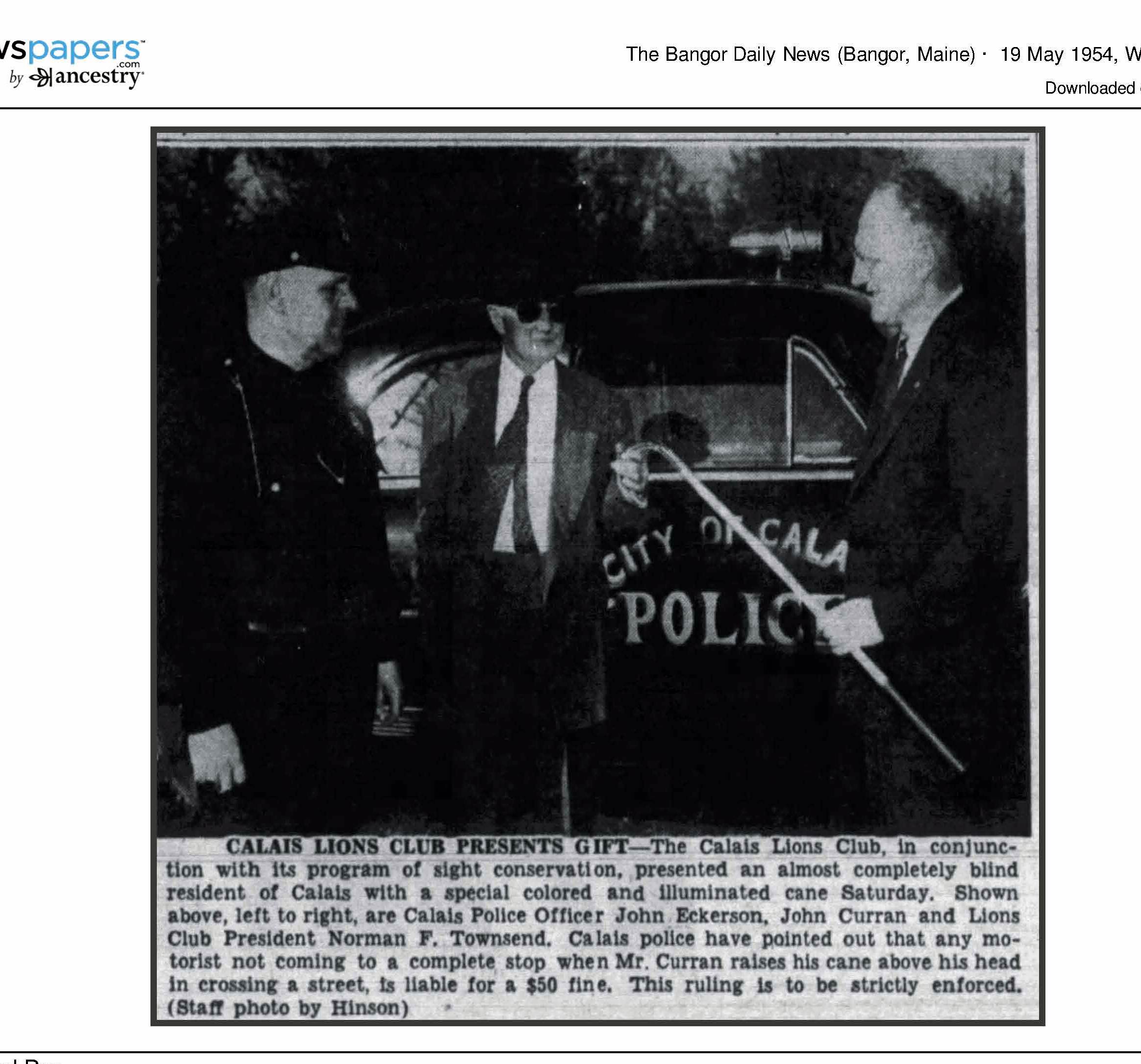

1954

For all of Uncle John Curran’s wayward behavior and his lack of any sort of regular work (he is listed in the 1930 Census under Class of Worker as “working on own account”), John was a fairly popular fellow in Calais. Perhaps the fact that he never drank and was a veteran of World War One made some of his other sins forgivable. Blind in his old age, the city did all it could to assure his safety and in 1954 the Lions Club presented him with an illuminated cane and warned residents that “any motorist not coming to a complete stop when Mr. Curran raises his cane above his head in crossing the street is liable to a $50. fine”. We find only one newspaper report of John being officially charged with bootlegging, a co-defendant in that 1927 case was his brother Eddie.

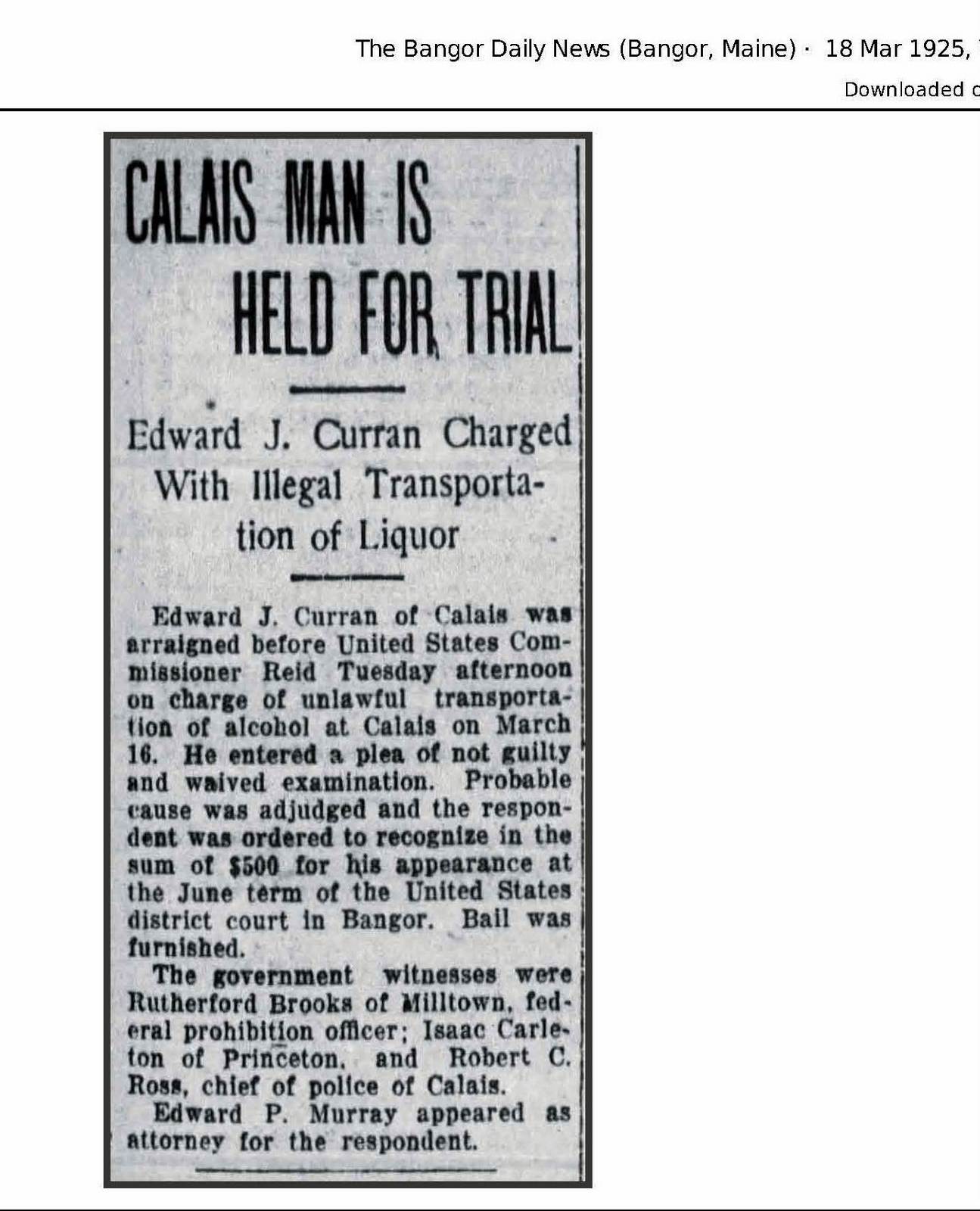

Louie’s Uncle Eddie Curran was a repeat offender

According to Louie his Uncle Edward “Eddie” Curran who also lived in the Union, was a much bigger wheel in the bootlegging business than Uncle John. Eddie worked for a bootlegger who supplied Eddie with a huge Valley Touring car to run rum to Boston Market. In the 1930 census his occupation is listed as “Automobile” which may imply the government knew exactly what Eddie was up to. If they didn’t, they weren’t paying attention. Eddie has a “rap sheet” too long to reproduce here.

Soon after Prohibition was enacted he was in state court charged with “being a common seller” of intoxicants and by 1925 he had come to the attention of the Feds. Many other charges followed over the years including one in 1927 in which brother John was a codefendant. In 1928 he was sentenced to six months in jail and a five hundred dollar fine for bootlegging and after failing to pay the fine another six months. In one case Eddie was found to be a public nuisance by the court and given a hefty fine. For a number of years Uncle Eddie made the court news at most sessions of court in Washington County and occasionally Federal Court in Bangor.

As Louie tells it nearly everyone living in the Union was involved in smuggling booze from Canada in some way. Harold Porter, an older boy and friend of Louie’s who lived nearby was a very strong swimmer and had a regular job smuggling Hand Brand Belgium rum. Harold would swim across the river when the tide was right below the Union Street bridge at a place called Indian Rocks and bring back a can tied to a rope around his neck. When he swam back to St Stephen there would be a couple of dollars and another can. He kept swimming until he returned to find only the money. Harold never knew who he worked for.

Louie recalls an incident in which the Feds confiscated a large quantity of bootleg alcohol and loaded it into a locked railcar in back of Louie’s place on Price Street. When they returned the next day the railcar was empty.

The Calais City Marshall, Bobby Kerr, was a Union boy who protected the bootleggers. His brother Herbie never had a job other than bootlegging and always wore a large overcoat with spacious pockets.

1874 map of Calais. The Indian Village at the end of Price Street.

Many will be surprised to learn that there was, for probably a couple of centuries and perhaps longer, a Passamaquoddy Village off Union Street in Calais. We can only speculate that the village was somehow associated with the multitude of salmon in the St Croix and their difficulty getting over Salmon Falls when migrating upriver from the ocean. The village can be seen in the 1874 map above. The village was just off Price Street near where Louie grew up. Louie was very fond of the inhabitants of the village and it appears he had other connections as well. According to his daughter Linda, his best friends growing up included many of the Sabattus family who lived on “Indian Hill” as it was then called. A newspaper article in the Calais Advertiser in 1935 reported the death of Peter Lacoote, aged 59 who was said to be “the last Indian to live on Indian Point at the Union.” However Linda recalls that Alice Sabattus, a tribal member, lived at Indian Point into the 1950’s and was the best friend of Esther, Louie’s mother. Further genealogy records show that Alice married Edward Curran, Louie’s uncle and notorious bootlegger, and had seven children all about the same age as Louis. Alice died at the age of 1971 and is buried in the Calais cemetery. She survived Edward by 36 years.

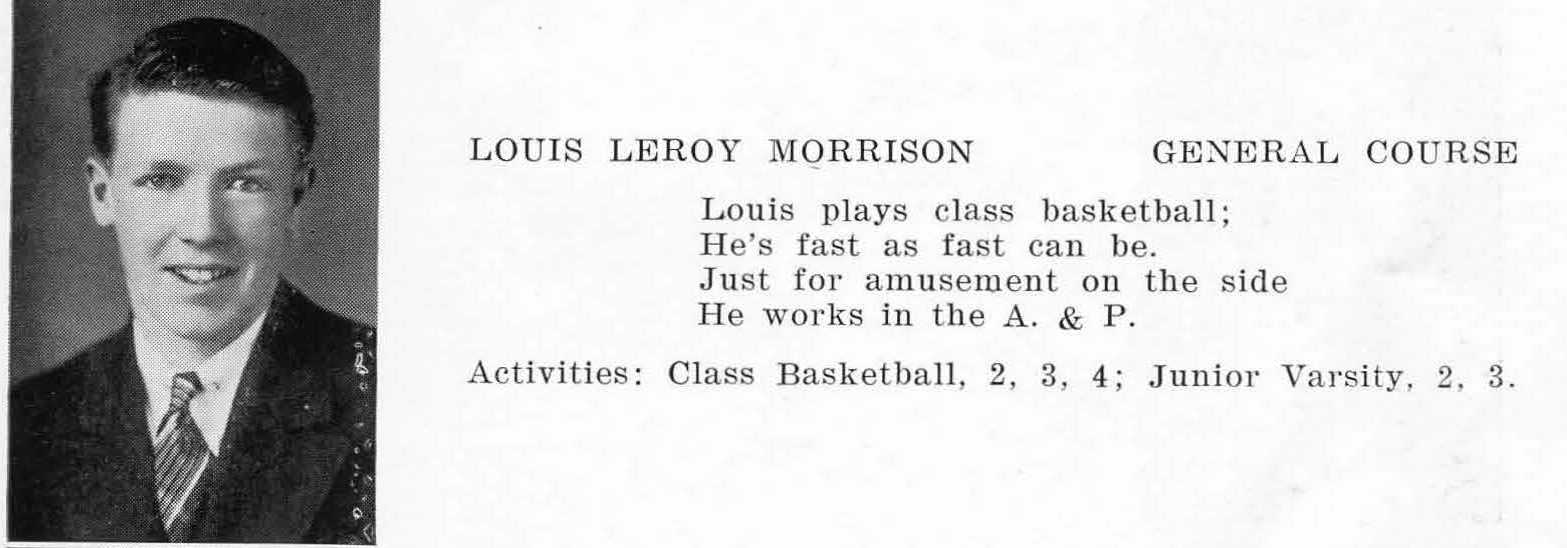

Class of 1940

Given all the distractions in his life one might have thought Louie would have had little interest in school. This was not the case. He attended grammar school on Academy Street and Calais Academy until graduation in 1940.

The A and P on Main Street where Louie worked in the 1930s. Now the Riverview Restaurant

Louie played some basketball in high school but had to work to help support his family from an early age. While still in school he worked, as his father had when Louie was born, at the A and P store on Main Street across from the St. Croix Hotel. Murray Tingley was the manager. Before the opening of the A and P “Supermarket” next door to what now is Joe’s Pizza there were four “neighborhood” A and P’s in Calais. Louie says only his store and the Washington St. store survived the opening of the “supermarket” and only because they were service stores. Many people objected to the idea of pushing a grocery cart around the new supermarket, they wanted the clerks to fetch, carry and bag their groceries from a list they provided. One evening in 1941 when Louie and Murray were locking up the store, they were approached by a couple of strangers who said “OK boys, we’ll take the keys.” This was the only notice they had that the store was closing but, as Louie says, it really didn’t matter. He and Murray were immediately offered full time employment by Uncle Sam.

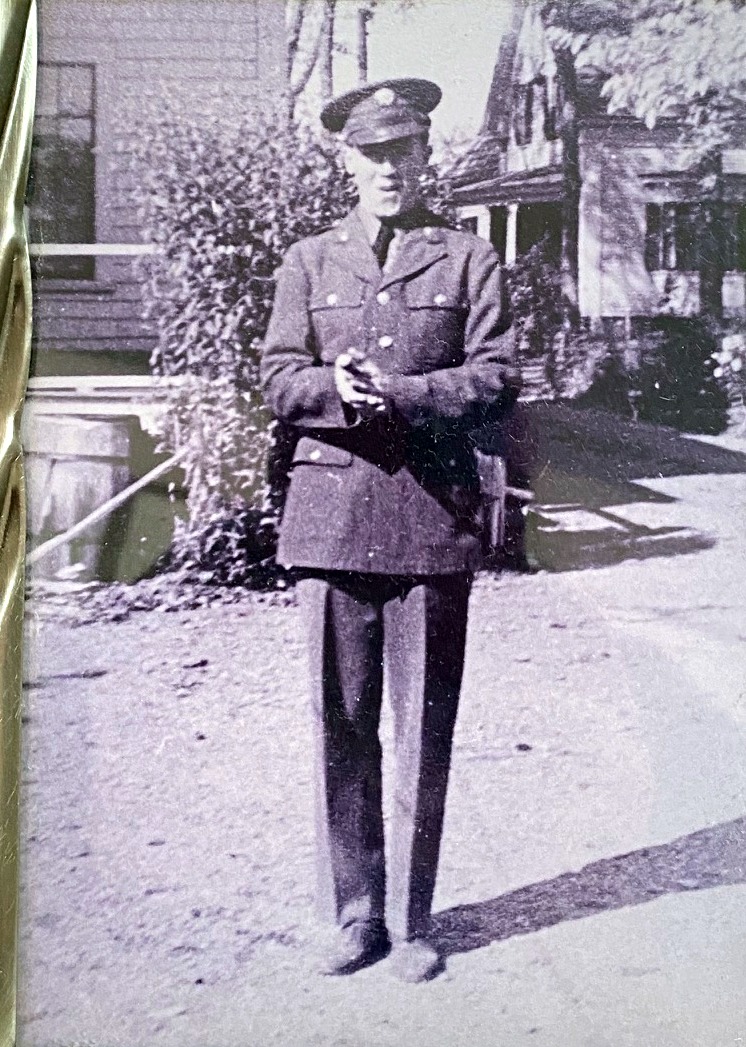

Louie in his new dress uniform

On January 17, 1941 Louis L. Morrison, described as a “Sales Clerk” became a soldier. According to the records he was 5 feet 8 inches tall and weighed 147 pounds. After basic training he was stationed in Louisiana, serving as an airplane mechanic.

Margaret Judkins

According to his daughter Linda, he didn’t much like Louisiana, the heat and humidity were too much for a Maine man although the area had one redeeming feature-a young woman named Margaret Judkins of Morehouse Parish, Louisiana.

married 1943

In 1943 when she turned 18, they were married. Soon thereafter he was transferred to Albuquerque where he served until the end of the war. He convinced Margaret to move to Maine and she agreed on the condition that their family take regular trips to visit her family in Louisiana. Naturally there was family-Linda, David and Debbie, all three are still much connected to this area. Linda in fact lives on Poole Street in the Union and from her front window she can see the back of the house she grew up in on Price Street. Linda says Louie kept his promise to take regular trips back to Morehouse Parish, Louisiana. She recalls some of the trips well. Mom, Dad and the three kids piled into the family car and headed South with $500 to cover expenses. It was somewhat of a culture shock for the Morrison kids who had no experience with racial prejudice. Linda recalls stopping at gas stations to use the bathroom and finding a long line at the white’s bathroom and no line at the one with the sign that read “Black’s Only”. The kids saw no reason why they shouldn’t use the empty bathroom and mom had a good deal of trouble explaining why it was not possible.

Louie was a valued employee at Todd’s for many years

After returning to Calais Louie and Margaret moved into an apartment on Main Street but soon bought a house on Price Street in the Union. They were living there when Linda was born in 1947. Louie worked at Todd’s Hardware until it closed in 1962 although he did other work such as working on the construction of Calais Memorial High School on Washington Street. Linda says that when she was growing up the Union had not changed much from her father’s childhood days. People were still poor and often just getting by but there remained a wonderful sense of community. Families didn’t go on outings, the neighborhood went on outings to the beach, to dig clams or to local events. Many didn’t have cars so they rode with neighbors. Linda was quite happy growing up on the Union even though some of the parents of her school friends refused to allow them to visit Linda on Price Street. Prejudices die hard and the Union’s image during Prohibition was only the latest in a long sequence of snubs to the Union. Even before the era of the bootleggers the Union had been called Irishtown. The first Catholic Church in Calais was on Union Street near High in the old town hall, far from the elegant protestant churches of the Eatons, Todds, Boardman and Murchies, the lumber barons of Calais. There were no Irish lumber barons although there enough Irish in town to eventually build a beautiful church on Calais Avenue.

Louie’s Barber Shop was in the St. Croix Hotel for many years

After Todd’s closed Louie went to barber school in Lewiston and opened Reds Barber Shop in the St Croix Hotel which he operated until the hotel closed in the early 1980’s. He then moved his shop to his home on Price Street. He had a loyal base of clients over the years but “Red” outlived most of them. Louis died on June 14, 2013 at age 91. Margaret had predeceased him in 1998. Linda says in later years there were fewer and fewer regulars who needed his services and this was hard on Louie as with every customer who passed away he lost a friend.