Tomorrow is April 27, and according to the eminent Calais historian Ned Lamb, April 27th was generally the day the chimney swifts arrived at the water company’s pumping station across from Customs in Milltown, Maine. The swifts took up residence in the building’s 75-foot chimney and spent the summer consuming mosquitoes and other pesky insects. Ned’s story about the swifts in a bit dated, being written in 1944 when chimney swifts were numerous and the pumping station had a chimney. When they arrived, the swifts darkened the sky over the pumping station and then descended in a beautifully choreographed and orderly procession into the unused chimney. As always, we’ll let Ned tell the story:

“It is nearly time for the swifts to return to their summer home in the Pumping House chimney and begin their helpful work in destroying mosquitoes. Because of the wonderful sight of watching these birds going to their nests in the chimney last year I was asked to write something about these friends of ours. Do not call them ‘Chimney Swallows’ any more as their proper name is ‘Chimney Swifts.’

“The Swifts are a separate class of birds and strange as may seem, their nearest relative is the hummingbird, according to ornithologists. Of course, they got their name from the swiftness of their flight which is also very smooth, while the swallows’ is undulation, like a nervous driver stepping on the gas and then taking his foot off, in rapid succession.

“The endurance of the swift is almost beyond belief. Very seldom does a swift light on anything during the day but keeps on the wing all day long. It gathers its food on the wing, and the material for its nest; it even mates while flying. There may be swifter flyers, but unless it is the Arctic Tern, there can be but few birds with more endurance.

“My good friend, the late Prof. Ora Knight of Orono and Bangor, in his exhaustive book The Birds of Maine tells how he watched a swift fly against a dead twig a number of times until it broke off and carried it away to help build the nest.

“The swift does not build its nest of mud like swallows, but of twigs and its own saliva. The twigs are carried to its nesting place and stuck into place with saliva which is very glutinous, and when one bird exhausts its supply the mate will carry on. One species of this bird in Southwestern Asia furnishes the material for the famed ‘bird’s nest soup’ of the Chinese.

“The swifts arrive here about April 27 and sometimes stay as late as September 16 when they leave for their winter homes in either Mexico or Central America. These American swifts are quite widespread as in summer they are found from Florida to Labrador. There are four or five different kinds in different parts of the world. Their natural nesting places are hollow trees or caves but when man began to build chimneys and abandon them even for a summer, the swifts found ideal nesting places and many a “ghost” has been traced to these birds in an old chimney, and many a chimney fire is started from the dry material from these nests.

“The swifts are small birds with very small feet and their tail feathers have the shaft extending beyond the soft edge; and the shaft is split, thus, with their small feet, affording them a three-point contact with the side of the chimney.

“The chimney of the pumping station is about 90 feet high and affords a nesting place for these birds whose numbers seem to run into the thousands, especially In late summer, when they have their young with them, Their food consists of any fly that they can catch on the wing, mosquitoes, moths and flies of all kinds. It must take an immense number of insects to feed these birds every day and they do a big work in keeping the number of these pests down in this neighborhood. They must range widely during the day.

“The birds are not noticed during the day but when the sun drops toward Todd mountain and the dimming daylight betokens the coming of the night they seem to appear out of nowhere, and as you watch there is a cloud of them flying in circles around the chimney top. Around and around they go, seemingly without any purpose, but suddenly a hundred, perhaps, will break away and pour down the chimney like water into a bottle. The others keep flying around and around. They seem to be waiting for the first lot to get to their nests so as not to jam the traffic. Around and around they fly until another bunch breaks off and goes down. The number diminishes until just before sunset [when] the remainder will dive down, as though they were afraid they would be caught out in the dark. How do they find their nests in that black hole? That is one of the mysteries of nature but find them they do and they raise their young, and live their lives, and fulfill their destinies, and who will deny but what they enjoy life with its swift flight, its hard work to make their living and raise their families, even more than men do, who seem to think they have to kill a lot of other men for glory.”

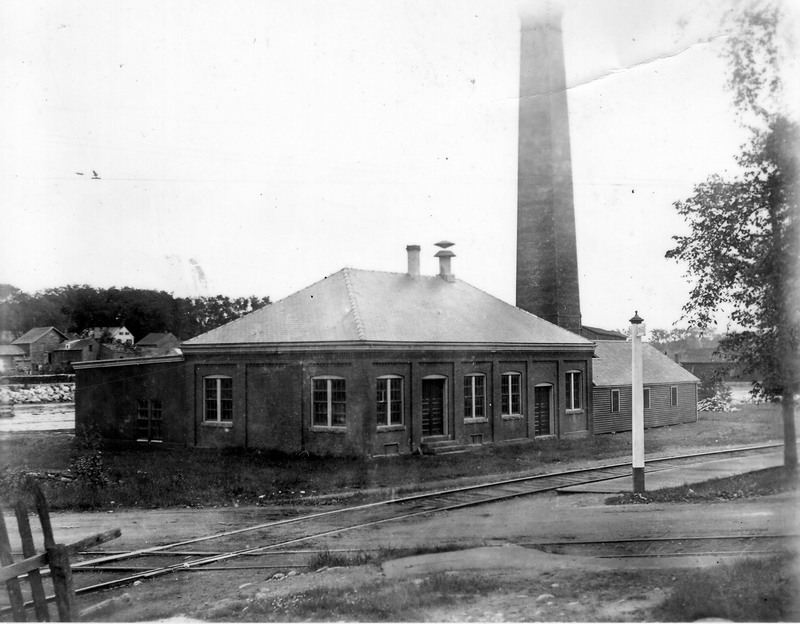

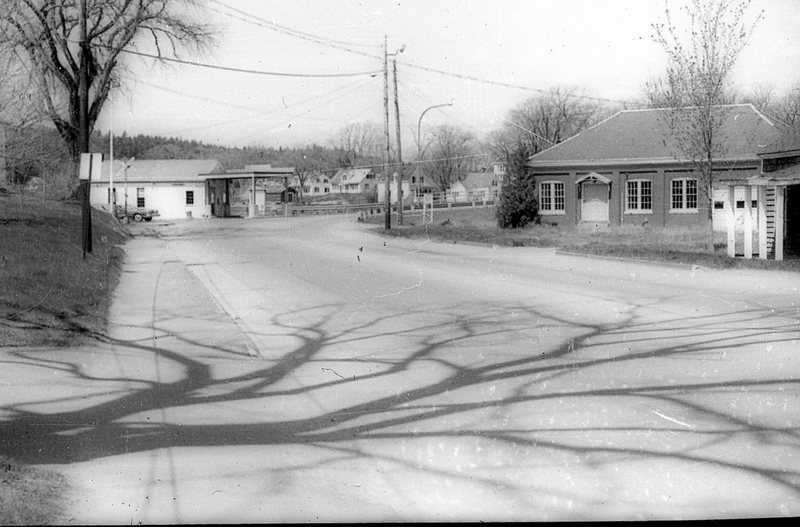

Most today know the pumping station although not its history. It still sits across from Milltown Customs but is today barely recognizable as one of the most important buildings on the river in the late 1800s. Its 75-foot chimney was demolished in 1946 and the loss duly lamented by Ned Lamb in 1946:

“A big change is coming to Milltown and a landmark is doomed. The Water Company’s chimney at the pumping station at the Upper Bridge is to come down. It was built in the eighties but times have changed. Then it was big boilers and steam engines drove the big Blake pumps. Now oil engines, with rotary pumps, taking only about ten feet of space each, will do the work. The old chimney has had quite ‘a cant towards Sawyers’ for a long time, and now the giant must come down. It seems too bad, when homes are so scarce, to destroy a thousand or so more, but when the Swifts come back about the tenth of April, from their winter homes is Central America they will find their summer homes, gone, and they will be looking for rents. Mosquitoes and flies will probably be far more plentiful this summer and perhaps it is well that D. D. T. has been developed, but we are warned to be careful how it is used around the house and where animals are. The men at the Border Stations will miss the wonderful sight of the birds going down to their nests. Tuesday evening two men with mauls knocked bricks out of one side and then ran like you know, and the 75-foot chimney squashed down in a heap.”

The water company building and water systems were constructed in 1887 by Italian laborers after the four towns, Calais, St. Stephen and the two Milltowns formed a rather unique utility—an international water company. For 20 years two large steam pumps in the building at Milltown, Maine pumped millions of gallons of water a month from the St. Croix River into a reservoir just across the river on Todd’s Mountain in Milltown, New Brunswick. A flag on a float in the reservoir was visible from the pumping station when the reservoir was full. Mr. Sinclair of Milltown. NB and Charlie Stubbs of Milltown, Maine manned the pumping station and stopped the pumps when the flag appeared.

Over the decades the system worked very well, even when there was far too much water in the river. Above is a photo of one of the floods which occasionally plagued the St. Croix. The Milltown bridge has been completely destroyed and the pumping station surrounded by water. The William Tell building is on the U.S. side on the site of the present Customs house. In those days U.S. Customs was located in a small ramshackle building next to the water company.

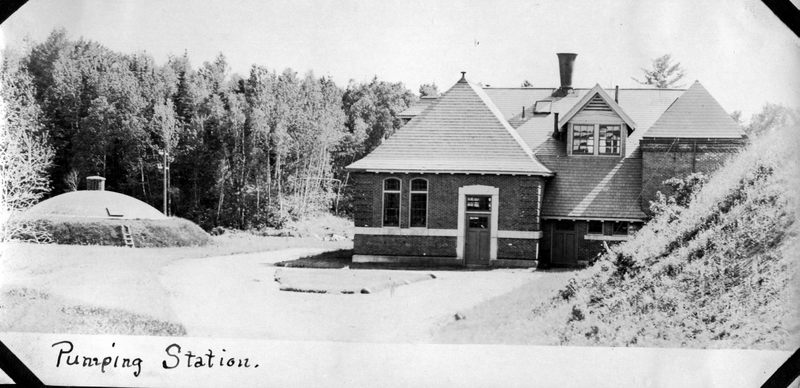

In 1904 the St. Croix Paper Company was beginning construction of a paper mill just a few miles upriver. This alarmed the downstream towns as they feared, quite justifiably, that the river would soon be polluted with sewage and chemicals. A commission was formed and an alternate water supply sought. The commission found the perfect solution, a clear deep spring at Maxwell Crossing just outside St. Stephen. The Maxwell Crossing pumping station, seen above, was constructed and began pumping an average of 22.5 million gallons of water a month the four and a half miles to the Todd’s Mountain reservoir and the four towns’ water system. Only in recent years has the international water system been abandoned to the regret of many. Calais restaurants and hotels can no longer truthfully claim to provide customers and guests with clean, clear spring water.

A final note on the chimney swift: While the Milltown pumping station provided nice digs for hundreds of swifts it wasn’t the only place a tired bird could spend the summer. There was plenty of room for overflow in the chimney of the Shaw Brothers Tannery in Grand Lake Stream which in the late 1800s was the largest tannery in the world. All that remained of the tannery in the 1900s—its chimney—can be seen above. After the tannery closed and the chimney was no longer used, it like the Milltown pumping station chimney, was ideal for the swifts. The loss of these old industrial chimneys and modern construction practices have left the swifts with fewer safe nesting opportunities. They are now a protected species.