Calais Annie H. Smith

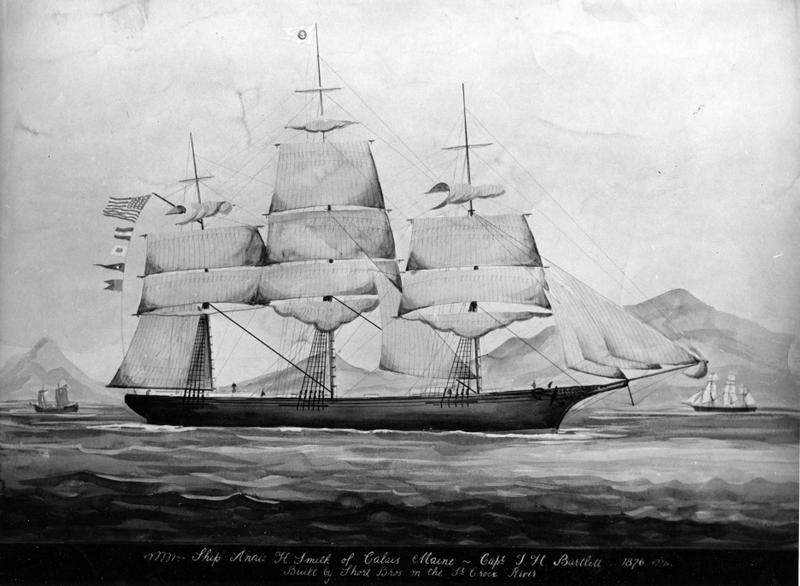

This painting of the clipper ship Annie H. Smith hangs today in Salem Massachusetts’s famous Peabody Museum. The background is the harbor at Hong Kong in the 1880’s. The caption reads

“Ship Annie H. Smith of Calais, Maine- Capt. J.F. Bartlett. 1876. Built by Short Bros on the St. Croix River.”

The Annie Smith was one of the most beautiful and fastest ships to sail the seven seas in age of sail. She was a clipper type square-rigger and one of the first so-called real Down Easters, a splendid design by men from way Down East and New Brunswick. These Down Easters were considered the most successful of all the wooden sailing vessels, and the Annie Smith was one of the finest.

The Annie Smith was built at the Rideout and Nickerson shipyard in Calais by the Short Brothers whose shipyard was just across the river in St. Stephen. The map above shows the location of the Rideout and Nickerson shipyard near the bottom of Barker Street in Calais. Today the rooms of the International Motel with a river view look directly over the old yard. She was the last large vessel to be built in Calais at 1472 tons and was built in Calais rather than at the Short’s St. Stephen yard because by 1876 ship builders on the St. Croix had been forced to consolidate their operations. The demand for sailing ships was decreasing—the age of sail was coming to an end. The Annie Smith was built for F. H. Smith & Company of New York and named after Mr. Smith’s daughter. She later married the son of the ship’s first commander, Captain Bartlett. The craft was later commanded by Capt. Roland Brown of Castine who took his wife and family of five children with him on voyages around the world. In 1883 he dropped anchor in Hong Kong, and a local artist, sitting high above the harbor on one of Hong Kong’s fabled hills, took brush to hand. Romanticizing the age of sail as we do we imagine what a wonderful this experience this must have been for Brown’s children, but in truth sea voyages were uncomfortable and dangerous even in a first-class ship like the Annie Smith. In fact, the passenger list from her maiden voyage from New York to Australia in 1877, at 74 days one of the fastest on record at the time, shows four passengers died on the journey. Three were very young children.

Above is the only photo we have of the Annie Smith. She is tied up to the dock at the bottom of North Street behind the library. The photo must have been taken just after launch before she left for New York to begin transporting passengers and cargo around the world.

Jane Sax (who many will remember) wrote a nice article on the Annie Smith for the Advertiser some years ago, and we will share it with you:

In the days of the schooners and the great clipper ships, the Calais waterfront was a great forest of swaying masts and it swarmed with men and wagons loading and unloading cargo from various ships’ holds and awaiting trucks. It must have been a sight to delight the eyes of children and adults alike, providing entertainment for many endless hours.

Shipbuilding was at its height in Calais from 1845 to 1878. Many vessels were designed and built in the many yards that lined the waterfront during that time. It is the “Annie H. Smith” whose story we will tell.

The “Annie H. Smith” was a large square rigger built in 1876, and she was the last of the large vessels built in Calais. At this time shipbuilders and designers were consolidating in order to continue with the production of sailing ships which were rapidly diminishing from our coasts and rivers. The “Annie H. Smith” was built by the Short Brothers of St. Stephen and Calais in the Nickerson and Rideout Yards. The ship was given an exceptionally fine rating but was the last ship to be built by them at Calais. The company did continue to design and build small vessels and schooners. The “Annie H. Smith was 222 feet long, 40 feet in breadth and 24 feet in depth of hold weighing 1,452 tons and was built for the F.H. Smith& Company of New York. The ship was named after Mr. Smith’s daughter who later married the son of the ship’s first commander, Captain J.F. Bartlett.

Imagine being in the large crowd that stood on the pier that day in 1876 when the “Annie H. Smith” was launched. It was just after lunch when the crowds began to assemble, an hour before the launching. Excitement was high, as it always was when a new ship was christened by the waters of the St. Croix and it seemed to grow as the time neared. The speaker’s platform on the pier held the mayor, the Short Brothers, Mr. Smith and his daughter. At the conclusion of the speeches, Miss Smith moved to the bow of the ship and smashed a bottle of wine against the keel christening it the “Annie H. Smith.” A cheer arose from the crowds as the huge square rigger slipped down the skids and into the water. It bobbed, then righted itself and floated majestically on the St. Croix. Sailors scurried into the rigging to unfurl the sails while below, several men were ready to work the capstan. Topsails, courses and fore-and-afters all loosened, and the men were standing by. Then came the cry, “Sheet fore and main top’sls! Let go aft! Ease away forward!” shouted Captain Bartlett. It was away, down the river into the Passamaquoddy Bay and into the open sea.

The maiden voyage of this vessel was from New York southeastward to Melbourne, Australia and it made very good passage in seventy-four days. They had cargo and about three hundred and fifty passengers. After discharging the last of the cargo in Sidney, the ship then sailed from Newcastle to San Francisco in sixty-two days. Then it went around the Horn to Liverpool with a cargo of wheat in one hundred-eighteen days. Going around the Horn was sometimes a rather grim experience especially in the winter. The captain and crew hoped for strong west winds which could shorten time around the Horn by a week. The wind at that time of year was piercingly cold, with a big sea that washed across the decks. Once the mizzen top-gallant sail blew out of its boltropes, a new sail had to be cut and sewn to replace it. But it was the westerly gales that helped the ship on and the wind from the east that was to be feared. When it came from the east, it had all the sting of Antarctic ice. The sea froze where it touched the bulwarks. Rain and sleet froze into the ropes. The decks were constantly awash. At night the lookout could not go on the forecastle head, for the seas came over it green and he would have drowned.

Gale after gale came from the east. Then a calm fell and for days the ship lay wallowing. At last the west wind came again and the ship made good headway hoping to pass the Horn without further misery. Then it faltered and stopped. From the east came the wind with fog, rain and gale in succession. Oilskins were useless. There was no dry place in the ship, nor a dry rag to wear. The seas put the galley fire out and there was often no warm food. Because the freshwater pump was on deck where waves stormed incessantly, it could not be worked for fear of mingling saltwater with fresh. So, the crew went thirsty.

Finally, around the Horn, the sea was still running huge and the cold was almost overpowering although the temperature rose about twenty degrees. Off the Falkland Islands, there was a snowstorm as bad as anything the Pacific had thrown at them but now the ship was in the Atlantic and warmer weather was near. Later the “Annie H. Smith” returned to New York, completing a most successful ’round-the world maiden voyage.

After the maiden voyage, the vessel sailed in trade, principally to parts in the Far East, making many fast passages from New York to San Francisco; it sometimes crossed the Pacific from the Orient to load California wheat for Europe, making several profitable voyages.

In 1883, the “Annie H. Smith” was commanded by Captain Roland B. Brown of Castine, Maine, who took his wife and their five children to sea. Later he made a very successful trip from Cardiff to Hong Kong.

The “Annie H. Smith” survived a most trying experience during the great blizzard which swept the Atlantic coast in March of 1888. Many ships were wrecked and others were extensively damaged. The ship had been towed from New York and dropped anchor in the Chesapeake Bay. It was preparing to load cargo for San Francisco when a terrific storm burst forth with all its fury. The ship broke away from both anchor chains. It was brought up with a manila hawser attached to a spar anchor to which the vessel rode successfully until the storm abated three days later.

Later, on one of the ship’s westward voyages around Cape Horn it was badly damaged by a storm off the Cape. The sails, rigging and spars were damaged, the rudder head was twisted off, but the ship made Port Stanley for repairs and soon proceeded to San Francisco.

After seventeen years as a most serviceable and useful merchant ship, it was converted into a coal barge. It was rammed and sunk by a steamship along the Atlantic Coast, an unfortunately ending to a valiant vessel.

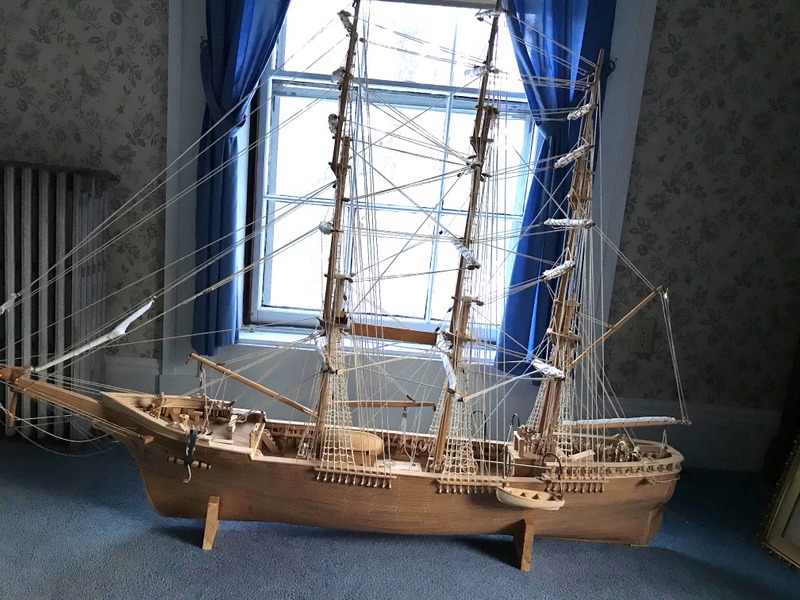

The sinking of the Annie Smith, the beautiful Downeast clipper ignominiously converted to a coal barge, was not the end of her. Everett Smith who lives down the coast is the great grandson of Captain Bartlett, the ship’s first captain and an accomplished builder of ship’s models. Naturally his piece de resistance is the Annie H. Smith, and he took much time and care constructing an accurate and lovely model of the ship which is on loan to the St. Croix Historical Society. Anyone interested in seeing the model should come to one of our monthly meetings. We’ll be happy to show it to you.