Google defines a fable as a traditional but unfounded story that gives the reason for a current custom or belief. This possibly describes the much publicized and uplifting account of our neighbors in St. Stephen providing the folks in Calais with gunpowder during the War of 1812 to celebrate the 4th of July even though the gunpowder was provided by the British authorities to charge the British cannon aimed at Calais which the British intended to reduce to rubble.

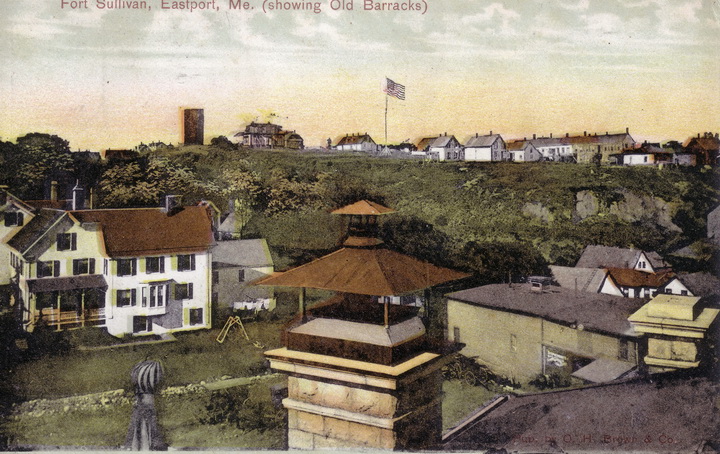

The American flag flies over Fort Sullivan Eastport

Calais and St. Stephen were unquestionably in a state of war in 1812. On June 18, 1812, the United States declared war on Britain ostensibly over the forcible impressment of American seamen into the Royal Navy and the blocking of American ports by the Brits in disputes over tariffs and embargoes. It was a rather senseless conflict and mostly about the lingering hostility between the countries over the War of Independence.

British burn the Capital 1814

While waged half-heartedly by both sides, the war was not without military clashes, notably the capture and burning of Washington by the British in August,1814 and a month earlier the capture of Moose Island, now known as Eastport. The British claimed Moose Island under treaties with the United States although the United States denied their claim and had constructed Fort Sullivan to defend the island. Fort Sullivan was held at the time by seven officers, eighty soldiers and a number of untrained militiamen. The British forces included four warships carrying 116 cannon, 900 sailors and 152 Royal Marines. On board the ship was the 102nd Regiment of Foot with 110 officers, 571 enlisted men and 23 musicians. To make matters worse for the Fort Sullivan defenders, the expedition was led by the legendary Admiral Thomas Hardy who held the dying Lord Nelson in his arms at Trafalgar.

The Fort wisely surrendered and remained under British control until 1818. Residents were required to sign an oath of allegiance to the King or leave the island. Many packed up their families and possessions and relocated to Lubec, then said to be a forest, which the British didn’t claim and apparently felt no need to occupy. Life changed dramatically on Passamaquoddy Bay after the British occupation primarily because smuggling, the primary business in Passamaquoddy Bay, became dangerous and unprofitable with the British occupying the entire bay.

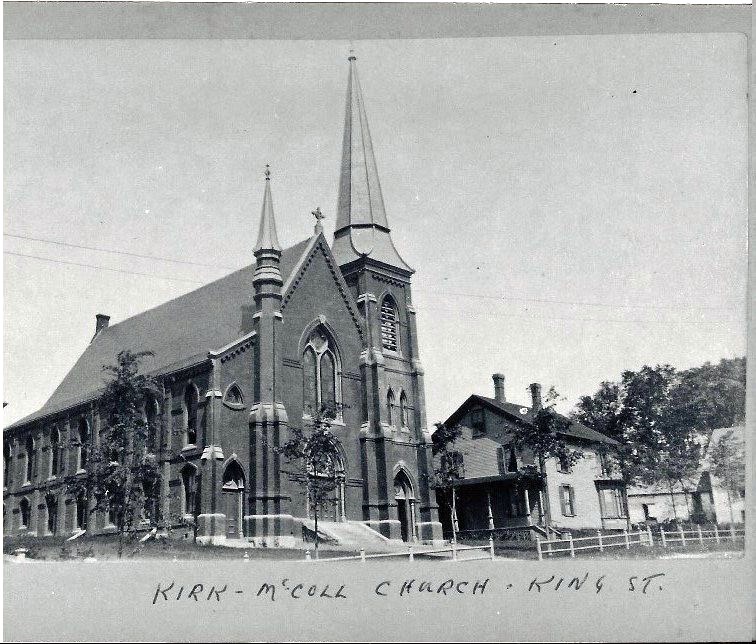

Named after Duncan McColl the original church burned in the 1880s

Up the river in Calais and St. Stephen there was much consternation over the state of war existing between the two countries. Thankfully there lived and preached in St. Stephen and Calais a Baptist minister named Duncan McColl. According to the earliest history of the area:

“Rev. Duncan McColl was one of the most remarkable and influential men that ever dwelt in the St. Croix Valley. Hardy, resolute, intelligent and pious, his name is interwoven with all the early life of St. Stephen and Calais; and the impression he made in both towns is too deep ever to be effaced.” Rev. I. C. Knowlton’s 1875 history of the St. Croix Valley

Doug Dougherty, noted St. Stephen historian, recounts that on June 28, 1812, after the declaration of war became public, Reverend McColl’s congregation gathered at the church in St. Stephen weeping and sobbing because the hostilities would prevent them from seeing their relatives and friends for some time. They were so upset McColl could scarcely get on with his preaching. The next day he suggested a committee be formed by influential citizens on both sides of the border to maintain law and order. The committee was formed, and peace and amity were maintained. From 1812 until the end of the war there was for all practical purpose an unofficial truce between Calais and St. Stephen. McColl was considered a traitor by some on the British side, but they were in the minority. He preached a Thanksgiving service in Calais in 1815 in which he quoted Colossians “Let the peace of God rule in your hearts” and it worked. When he preached in Calais the Commander of U.S. troops attended his services as did the British Commander when he preached in St. Stephen.

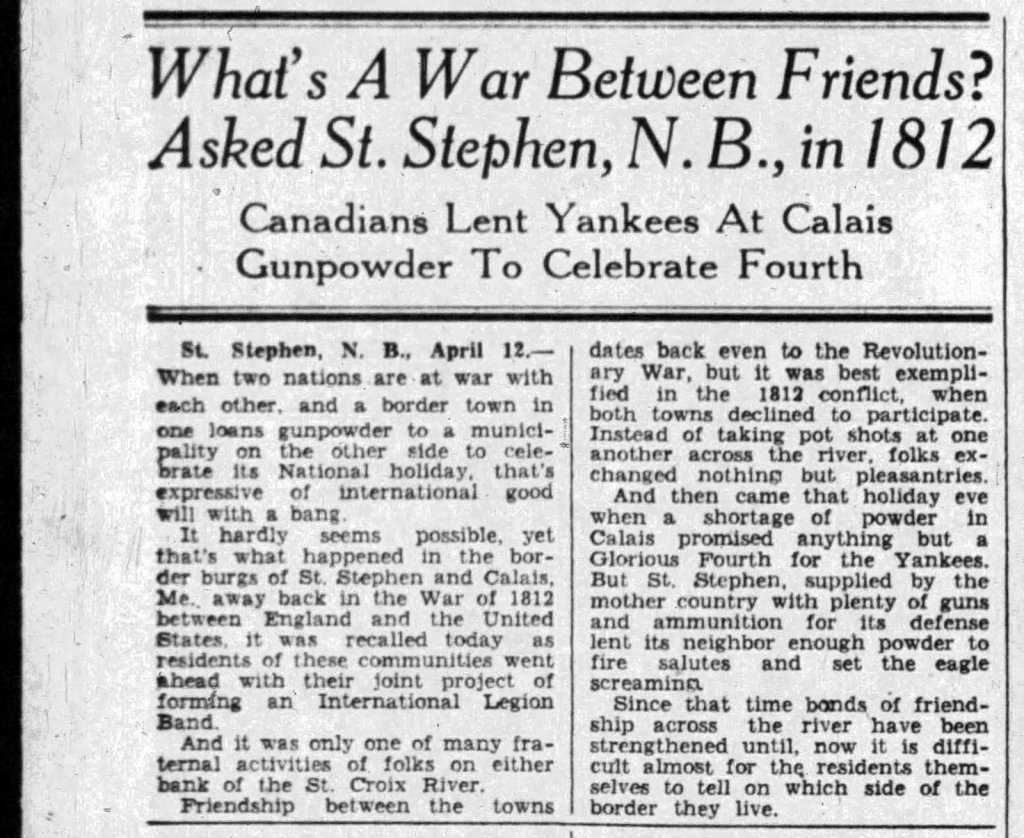

Nanaimo News British Columbia 1980

Portland Press Herald 1948

Thus it should not be surprising that from this extraordinary relationship between warring parties tales or fables would originate, and the gift of gunpowder story is a good example. From the late 1930’s hundreds of newspapers, Time magazine and many other historical sources have repeated the legend of the gift of gunpowder. I say legend because the historical evidence for the story is rather thin. There is no mention of the incident in any of the early histories of the area or in the more scholarly works done later. The first mention I can find are two articles written in 1938 in New Brunswick newspapers.

The Fredericton Daily Gleaner reported August 22, 1938:

Over and over the story has been told of the time when gunpowder was stored here in the early days and that when the military authorities instituted a checkup of supplies, St. Stephen had to confess that they had to give it to Calais so they could have a darn good rumpus on the 4th of July but St. Stephen never had any more gunpowder entrusted to it by the military New Brunswick. At least not then.

The St John Globe carried a similar article. By the late 1940’s there were many more articles in the national press reporting the same story but the 1957 Van Nuys California News had fleshed out the details.

Crowder’s Corner Van Nuys California News Feb 28, 1957

By CHARLES CROWDER

The year 1812 was a tragic one for Maine. The country was at war with England. The British had pretty well overrun the state. One of little towns that had not been captured by the red coats was Calais, that lay across the border from St. Stephen, Canada.

Ahab Watson, in charge of the headquarters of the town’s defenses, sat on the front porch of his home and contemplated the plight of his people. He lifted his telescope and focused it on the headquarters of his friend, Capt. Pine, of the Canadian militia.

ASKS BOMBARDMENT

He saw a red coated major of the British Regulars dismount from his horse and enter the large frame house, and wondered what would transpire.

As Major Barber entered the headquarters office, Capt. Pine rose with a smart salute. The major and his subordinate were soon studying a military map of the territory. The British officer indicated a spot on the map.

“Captain, the obvious vantage point from which to strike at the Americans is here, at Calais. You will entrench your men along the river and bombard the city.”

Issues Warning

“But, sir,” remonstrated Capt. Pine, “We have always been friends of the people of Calais. We couldn’t fire on them.” “Captain, this is war, and the Americans are our enemies. You have your orders, now see that they are carried out.”

“Major Barber, I don’t wish to disobey orders, but it is impossible to carry them out at present.”

“And why not?” asked the major.

“We haven’t any gunpowder.”

The British officer stamped out of the room with a promise that gunpowder would be sent at once, and a warning that it had better be used.

Gunpowder Arrives

Hardly had the Major departed on the road to Quebec, then Capt. Pine hurried across the river to tell his friend, the bad news. He joined Ahab Watson upon the porch, “Yes, Ahab, the major was in rather a dither. He says we’re at war, so that makes you and me enemies. Too bad we have to settle our differences with gunpowder, now, instead of playing checkers.”

“Well, son, just be careful with that gunpowder. Somebody might get hurt.”

In due time a load of gunpowder arrived at St. Stephen. Day followed day, and the war surged back and forth across the country; yet somehow the militiamen of St. Stephen never got around to cannonading the town of Calais.

Understands Situation

The war ended with no shots ever having been exchanged across the St. Croix River. A short time after the war was over, Major Barber again paid a visit to Capt. Pine, “Captain, the war is over now, but I am forced to take you to task for disobeying my orders to fire upon Calais.

‘ “We didn’t mean to disobey. orders, sir. But the Americans are our friends. Why, every time we had a fire, we had to borrow their equipment to fight it with.”

The major was understanding. Then he thought of something else.

Seeks Explanation

“The gunpowder, captain. Since you’ve not used it, I’ll send a detail here to transport it to the fort at Quebec.”

“But it has been used, major.” The captain’s face turned as red as his tunic, as he explained the mystery of the missing gunpowder. “Well, sir, in the middle of the war, when the Fourth of July came along, the Americans in Calais wanted to celebrate. their Independence Day but they had no-well-we gave them the gunpowder to make firecrackers.”

British occupation of Maine War of 1812

Of course, Mr. Crowder’s account must be taken with some skepticism. The Brits had not actually overrun the entire State of Maine. They did take Machias, Castine and some other ports in Eastern Maine. They also occupied Robbinston briefly. When the British fleet hove into view, Robbinston’s General of Militia John Brewer quickly negotiated a surrender and the Robbinston militia abandoned their gun emplacements behind the Congregational Church and decamped to Machias. Ahab Watson was not then or ever a resident of Calais as far as we can tell, and Captain Pine is equally unknown. David Facey-Crowther was commander of the local New Brunswick Militia.

Is there any truth to the gunpowder story? Some years ago, a college student Hannah Newson contacted me as she was writing a paper about the story. She conducted extensive research on both sides of the border including interviews with local historians, and a search of primary and secondary sources. She followed every lead on the internet. Her conclusion was that the story was possibly true but “there is not sufficient primary evidence within the aforementioned documentation to state what actually happened.” When Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper repeated the story at the opening of the third bridge in Milltown in 2012 a reporter wrote in the Moncton Times that the story, while appealing, “was probably not true.” Allan Gillmor a former mayor of St. Stephen acknowledged the story “may be nothing more than folklore.”

St John Telegraph Journal 1976

Whatever the truth, on the 200th birthday of the United States in 1996, we acknowledged the generosity of our good friends across the border and returned the gunpowder. While only sawdust with a sprinkling of gunpowder on the top it was the gesture that counted. It is a sad state of affairs today when our best friends may have need of the gunpowder to protect themselves should the implied threats of our President be carried out. Even if just bluster the consequences have already been dire. The people of the country which fought beside us in two World Wars, Korea and Afghanistan now finds themselves adversaries if nor enemies, the bridge over which we returned the gunpowder is largely unused and the economies on both sides of the border may soon be devastated by tariffs. We badly need a Reverend McColl.