USS Cony Hampton Roads 1957

The USS Cony was a destroyer launched in 1942 at Bath Iron Works. It was named to honor a local man, Joseph Saville Cony, for his service in the Civil War. Joseph Cony was born in Eastport in 1834 and married Ellen Vesta Holmes of Calais on October 22, 1863. Ellen was known as Nellie and is the author of “Nellie’s Diary” a fascinating account of a young woman growing up in Calais in the 1850’s. Joseph Cony died in 1867, only thirty-three years of age. His body was never recovered and there are gravestones memorializing his death in both the Calais and Eastport cemeteries.

The USS Cony lived a longer life. She served in the Pacific during World War Two, being nearly sunk by dive bombers during one encounter and suffering many casualties in the engagement. After repairs she returned to service and was engaged heavily with the Japanese during the battle of Leyte Gulf. She also took part in the ill-fated Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba in April of 1961 and in 1962 was one of the ships blockading Soviet ships off Cuba. In October 1962 the Cony intercepted a Soviet submarine B-29, an incident which nearly led to war between the United State and the Soviet Union.

Joseph S Cony

Joseph S. Cony was born in Eastport in 1834 to Joseph S. Cony Sr. who was born in Massachusetts in 1807, and Almira Bailey born in 1810. He may never have met his father or if he did, he certainly would not have remembered the meeting.

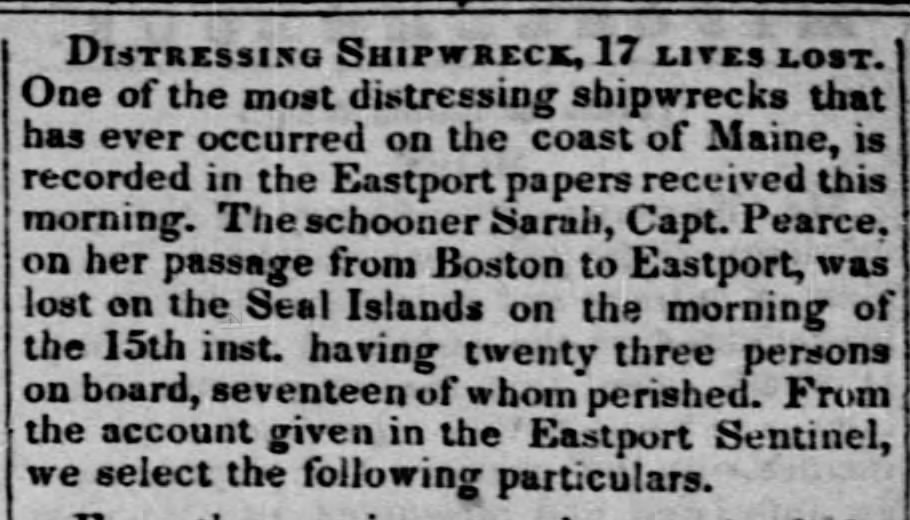

The Liberator newspaper October 18, 1834

In October 1834 Joseph Cony, Sr. died at sea just miles from his home.

From the Eastport Sentinel: 1834

WRECK AND LOSS OF LIVES.

It is with painful feelings that we report the loss of the schooner Sarah, Thomas Pearce, master, on her passage from Boston to this port. The state of the wind and weather on 30th Sept., her regular day of sailing from Boston, was favorable, and her arrival here on Thursday and Friday was expected almost as a matter of course.

As, however, the weather in vicinity became stormy, and the wind blew with much violence the latter part of Wednesday and nearly all of Thursday, it was thought probable that she did not leave at her appointed time, that if she did, she had harbored or hove to, there was no particular anxiety of her safety until Sunday noon, when this opinion and fear became general, that some accident had befallen her.

And so it proved. Early on Monday morning, news reached town, that a piece of her stern, two birth boards, a bucket and the top of a trunk had been picked up, near Little River, which Capt. Lincoln, of the Compeer (who left here Saturday forenoon, and anchored off Little River) identified as belonging to this missing ill- fated vessel. These sad tidings spread with rapidity, and by nine o’clock, few of our citizens thought or spoke of ought, save the Sarah, and the unfortunate beings attached and likely to have taken passage in her. The arrival of the Mary Elisabeth, Capt. Bowman, at about half past ten o’clock, the same forenoon, relieved some fears, while it changed others into certainties.

Cat. Bowman stated that the Sarah left Boston on Tuesday evening and had ten or twelve passengers on board. Of these, it was placed beyond doubt that Mr. Joseph S Cony and Mr. Ebenezer Starboard, of this town, were two, and that Peter Goulding, Esq. of Perry, Mr. William Fowler of Lubec, and Mr. Wiggins, a young gentleman of St. John, were among the others. This dreadful intelligence soon reached every habitation, and filled many a heart with anguish as the circumstances of the case rendered it but too certain that all, or nearly all on board had been drowned. The anxiety, fear and a watery grave which filled every breast, throughout the day, cannot be described.

There was indeed hope. A fishing vessel arrived and reported that signals had been flying upon the Seal Islands since Thursday -raised, as all now fondly trusted, by their shipwreck townsmen. Meanwhile, Mr. Samuel Mowry of Lubec, who had heard of the disaster some hours earlier than it was known here, had gone down the coast in search, and a number of our citizens had left town on the same dreadful errand.

Early in the evening, the Pilot Boat No. 2, Capt. Connelly, arrived with the survivors, six in number, Peter Goulding, Esq of Perry, a Mr. Jeffries, of New Brunswick, the stewardess and three seamen–all others, seventeen in number, perished! These were Capt. Pearce and son, Mr. John Swett, Mr. Ebenezer Starboard, and Mr. Joseph S. Cony, of this town, a son of Hon. J. C. Talbot, of East Machias, Mr. William Fowler and Mr. Featherson of Lubec, Mr. Wiggins and a Mr. Smith, of St. John, Mr. Darling. of St. Stephens, a seaman and two forward passengers, the cook, and two others, whose names are unknown.

(A description is then given of an account of a survivor who described how they had nearly avoided the rocks which holed the ship)

…. had she gone a few feet further, (her length perhaps) she would have gone clear, our melancholy recital would have been spared, and those whose loss we deplore, would have been among us, alive and happy. But it was otherwise ordained; they drove upon the rocks sideways, and in fifteen minutes, the sea had cleared her of every soul on board! Six, as we have said, gained the shore—and seventeen found a grave! The survivors cannot be expected to speak intelligibly of what occurred after she struck. They do not. But yet they do speak of the shriek–the wild despairing cry–the lament for wives and children–and the prayer -from lips that never speak again! But enough- the little that we know must be spared, for-we cannot narrate it.

And now, what an awful visitation of God is here! FOUR widows–and TEN fatherless children here—perhaps as many more elsewhere! –and bleeding hearts- -these who shall number? There is CONY, the young, the good; Cony, the beloved of all: who will not miss him: who will not mourn for him, who will not sympathize with her–with his kindred and there is PEARCE-as fearless a seaman as ever trod a deck! Pearce, whose history was filled with storms and shipwrecks- with losses, misfortunes and afflictions. And his son -where is he? where- -but beside his father in the deep. In that same capacious grave lie STARBOARD and each loved, regretted and mourned. And SO with Fowler and TALBOT–SO with the others, who, though strangers to us, have kindred friends to lament their untimely end.

He who established and conducted this paper for fifteen years was never required to record an event so afflicting to his neighbors; and it be long before its columns shall be witness to another.

The Eastport Sentinel reported on November 26th that the body of Joseph Cony came ashore in Nova Scotia on November 26th. His body was returned to Eastport and is interred in the family grave.

Cony Park Eastport

If Joseph Cony had been born when his father died, it was only just. Certainly, what he knew of his father must have been related to him by his mother and friends. The Cony homestead was at Cony Beach off Broad Cove near Shackford Head. Cony Beach Trail is just off the parking lot at Shackford Head State Park as is the foundation of a house which is probably the birthplace of Joseph. After his father’s death however it seems Joseph and his mother Almira moved into the home of Oliver S. Livermore in town.

Frontier Bank Eastport

Livermore was for many years President of the Frontier National Bank of Eastport, an early and prominent citizen of Eastport. The Livermore home was built in 1821 by master builder Daniel Lowe. Oliver S. Livermore’s father was Capt. Joseph Livermore who commanded the first Eastport to Boston packet, the Friendship, in the early 1800’s. Kilby’s history of Eastport records this interesting anecdote about young Oliver and the first horse to visit the town.

Samuel Jones of Robinson swam his horse across the channel from Pleasant Point to Carlows Island and rode along the bars and beaches and through the woods to town. The late O.S. Livermore told me of his going with other children to see this strange animal in a barn, and that one little fellow, who saw Mr. Jones pass, ran home shouting to his mother, “There goes a man sitting on a cow that ain’t got any horns.”

The 1850 census finds Joseph and his mother living with the O.S. Livermore, his wife and many children in Eastport. As Livermore was a prominent citizen and successful businessman, and we can assume Joseph had many educational and societal opportunities beyond the reach of most boys in the Eastport of the 1840’s. Still, it appears the father he never knew was his idol and the sea his lodestone and at the age of 16 he took to the sea. He wrote his mother Almira at the beginning of the voyage.

At Sea, July 18th, 1849

My Very Dear Mother,

Here I am at sea, where I have so long wished to be, and I would like very much to be ashore too. I don’t mean by that I am sick of it, no such thing, for I like it very well, indeed, much better than I expected to. I have to work hard enough, and it is hot enough- for we are only 7 degrees N.(north) of the line (equator). There is a great deal more work to be done than I expected but the men & officers all tell me that there is a great deal more than is common because the ship was in very bad order when we left port, and when we get her fixed up a little we will have it easier. There is one thing in which I am very much disappointed, and that is in not having watch and all hands are on deck from dinner till dark. All the time I have to myself is from 8 to 12 in the A.M. every other day, making only 2 hours a day on an average all of which is taken up with looking after my clothes etc. so you see I have no time to study or read. I am three inches smaller round the waist than when we left Boston. We will make a very long passage of it and you mustn’t look for me home to the 1st of July (next year). We have a great crew, although I am firm friends with all of them. The Sailmaker is an Englishman, he has been to Calcutter 11 times. The Carpenter is a Sicilian from Palermo, 3 of the men are Americans, 1 is a Frenchman, 1 Dane, 1 Norwegian, 1 Swede, I Italian. We did not get the N.E. Trades as expected for they were due E. Sometimes E.S.E. which obliged us to lay close hauled all the way. We have not had any heavy gales of wind, although we had a couple of light breezes which obliged us to double reef the top sails, and I cat’s paw in which we split our jib & foresail. We have sighted a number of vessels but have not spoken [to] any, although we passed so near an English Man of War Brig as to show him our Bunting and the Captain brought a speaking trumpet on deck, but John Bull didn’t seem inclined to stop for us. I am very tired and can not write any more now, although. I feel as if I could write on all day, if I shouldn’t get a chance to write any more, before I send this give my love to all. Tell cousin Lou (?) I couldn’t write to him from Boston & he will have to wait till I get back. Now don’t worry about me will you, for we shall certainly be back by the 1st of July and perhaps by the 1st of June. I should feel a great deal happier if I knew you would not worry about me. The men are all very kind to me and are willing to do anything for me. I have quite a class in reading with the Dane, the Norwegian, Caspar, Nick the Swede & the Italian and they all get on very well. I have learnt the Swede to write a little already and he is improving rapidly. The Bible is their reading book. The Bible Society sent aboard a testament for each man before we came away. The day before yesterday we caught a porpoise, and all hands have been living on him since. We have also caught some Bonito. When you write to Bangor be sure and tell them I am getting on first rate, for I want Mr. John Curtis to know that I ain’t another Castanus, he was so sure I would be sick of it and never go outside of Quoddy light again. Don’t forget to send my love to them all though will you. I am well, strong and hearty as I can be but I am very tired when it comes night and as there is no other boy aboard except the cabin boy, I have no time to learn seamanship such as knot tying, splicing, etc. all my time being taken up sawing wood, turning the grindstone, sweeping decks, etc. But the men tell me I will have a chance bye and bye when we get to rights. I do not enjoy my breakfast at all for the coffee we have would be bad enough with milk, but I can’t bear it without so I have to put up with water which I wouldn’t mind if it was cold but it is rain water that falls on deck and runs into a tub. Oh, if I only I had a drink of pure sparkling cold water.”

According to Eastport Historian Wayne Wilcox on whose research I have relied, Joseph Coney remained a seaman after this voyage and in 1860 was living in the home of Ship Master Maurice Bailey in Eastport. Then came the Civil War and Cony was not long in joining the U.S. Navy where he continued to rise in the ranks due both to his seamanship and courage. He led several small boat expeditions along the Carolina coast and was promoted to executive officer on the U.S.S. SHOKOKON. In one encounter Coney’s landing party surprised a confederate encampment, capturing 10 men, an army howitzer and 18 horses. He also destroyed a salt works and captured blockade runner. As a result of his gallantry, he was again promoted.

The second battle for Fort Fisher, naval units to top left in white

It was, however, at the Second Battle of Fort Fisher in early 1865 that Cony most distinguished himself. Fort Fisher protected the port of Wilmington, North Carolina, then the last port held by the Confederacy and vital to their supply of munitions. The attack was a joint assault by Army and Naval Units. In the painting above the naval units are in white. Wayne Wilcox describes the battle:

Cony, while attached to the U.S.S BRITANNIA, participated in the 1st unsuccessful amphibious attack on Fort Fisher on 24-25, December 1864. This is where fellow Eastporter, Edwin R. Bowman, received his Medal of Honor for gallantry. By 13 Jan. 1865 Cony was serving on the U.S.S FORT JACKSON when he volunteered to be one of the 2,000 Sailors and Marines to attack Fort Fisher for a second time on 15 Jan. 1865. The Union army consisted of 8,000 men and the Union Navy consisted of 59 ships. Facing this force was a total of 1,500 defenders of Fort Fisher.

At 3:P. M. on the 15th of Jan. the Union forces landed. The Army advanced through woods while the Naval Brigade charged across an open beach. The Confederates fired at the Brigade point plank range. Sailors and Marines were cut down by the score with heavy musket fire, but the Brigade pressed on and the fort was finally captured. From this second attack on Fort Fisher more than 35 sailors and Marines were awarded the Medal of Honor. Captain Cony was honorably discharged from the Navy on 7 November 1865.

After the Civil War Cony returned to Washington County where his wife, Ellen “Nellie” Holmes Cony awaited him. They had been married at the Holmestead on Main Street in Calais, now the home of the St. Croix Historical Society, on October 22, 1863. They did not remain there long. Cony was man of the sea and by the end of the war had acquired a reputation as man capable of commanding nearly any seagoing vessel. By early 1867 he was given the command of the City of Bath, a steamer built in Bath in 1862. It served as a troop ship during the war and in 1867 was sailing the Boston to Savannah Georgia route.

The City of Bath had a somewhat checkered history. On June 4, 1864, it collided with the steamer Pocahontas near Cape May, New Jersey. The Pocahontas sank within 20 minutes. 40 lives were lost. Captain Lincoln was then the captain of the City of Bath and he was not found responsible for the tragedy. On February 10th, 1867, the City of Bath, now under the command of Captain Cony, was beginning her run to Savannah from Boston when about 35 northwest of Cape Hatteras a fire broke out near the forward coal bunkers. Captain Cony and the crew fought the fire for several hours without success and finally, all hope of saving the ship lost, Captain Cony gave the order to abandon the ship.

Georgia Journal February 20, 1867

According to the report in the Macon Georgia Journal of February 20, 1867:

At the time of her taking fire which occurred about five miles North-west of Hatteras she was on her voyage from Boston to Savannah with a large, assorted cargo. There were twenty-six persons in all on board. The fire broke out in the coal bunkers between twelve and one o’clock Sunday morning the 10th inst. and is believed to have originated from the bursting of a hanging lamp suspended over one of the bunkers. Every effort was made to extinguish it, the Captain working and directing the crew at the same time. It gained upon them rapidly however and between three and four o’clock the flames burst out from the forward hatches and believing that all further efforts to save her would be useless, the vessel was abandoned. The boats three in number were lowered. The passengers and five of the crew entered the first a metallic lifeboat which was soon afterwards swamped by striking the guards of the steamer and all on board of it was lost. Another party of seven took possession of the second boat and have not since been heard from. The metallic lifeboat after being righted was occupied by Captain Cony, the second Mate a Savannah River Pilot, the first Steward and four others. Nine of the crew, including the Engineer, entered the third boat, also a metallic one. The boat containing the Captain and others was soon afterwards capsized and all on board were lost except the Captain and mate who were rescued by the party in the Engineer’s boat. On Sunday afternoon the schooner Laura S. Watson was hailed and in coming to the assistance of the party a high wind prevailing at the time and she collided with the boat and overturned it. The boat was six times righted and overturned and the crew one by one becoming exhausted and the schooner being temporarily unable to render them assistance on account of the heavy sea dropped off and were drowned. After desperate exertions, four of the crew were saved.

There were newspaper reports claiming some rescuers thought Captain Cony was intoxicated during the rescue attempt, but this was strongly denied by the four surviving crew members.

From the Macon Georgia paper:

Captain Joseph S Cony was a native of Maine and a relative of ex-Governor Cony and during the war distinguished himself in several naval engagements as commander of one of the U. S. gunboats participating in the Fort Fisher attack with great gallantry. Captain Cony commanded the steamship Wm Tibbets consort of the City of Bath until within the last two months when be assumed command of the latter vessel The report that Captain Cony was under the influence of liquor was contradicted by Mr. Davis one of the crew of the lost steamer and is universally considered a slander inasmuch as he was not addicted to the use of spirituous liquors.

I’ll let Wayne Wilcox, Eastport historian, tell the rest of the story:

After the tragic death of her husband Ellen returned home from Boston as a young widow, to Calais to live in the family cottage next to the “Holmestead”. Joseph and Nellie (Ellen) never had children and she never remarried. Upon her return to Calais, Ellen became active in community affairs and was strongly devoted to the Grand Army of the Republic veteran’s organization. Ellen’s sister, Agnes, named her youngest daughter “Josephine Cony Moore”, born Jan. 8, 1869, and died Jan. 3, 1956, in memory of Ellen’s husband Joseph. Ellen Cony died at Calais on 6 Feb. 1920, age 79, and is buried in the Holmes family plot. Next to Ellen’s headstone is her husband’s stone with a simple inscription “Joseph S. Cony, Lost at Sea, Feb. 10, 1867„ age 33.

A footnote:

The home where Joseph and Ellen Cony probably spent their wedding night on October 22, 1863, is the Holmestead on Main Street in Calais. Built in 1850 by Dr. Job Holmes and his wife Vesta, it was a home usually full of life as evidenced by Ellen’s diary of the home in the years before the Civil War. On the night of her wedding, however, a pall hung heavily over the celebrants. Only a few months earlier Ellen’s brother Frank had died along with several other local boys taking Marye’s Heights from the Confederates in Fredericksburg. Dr. Job Holmes was stricken with grief and never recovered from the loss of his son and was soon to follow him to the grave. Joseph Cony’s mother Almira who had lost her husband to the sea in 1834, died at St. John, N.B. in 1862 so was not alive to grieve her only child. Both her husband and her son were in their thirties when they lost their lives st sea.