The building of the atomic bomb during World War Two, known as the Manhattan Project, was perhaps the most secretive military and scientific operation ever undertaken by the U.S. government. Given the tens of thousands working on the project in several locations across the country it is remarkable the secret was as well-kept as it was and the fact remains very few knew the exact objective or extent of progress on the project. The thousands of workers knew, of course, they weren’t working on building a better mousetrap and that their work was war and weapons related; but only a handful had what we would call “insider” information and one of these was a Calais woman- Virginia Olsson. It was only after the war that articles were published in national newspapers revealing her position as confidential secretary to the top officials in charge of the Manhattan project.

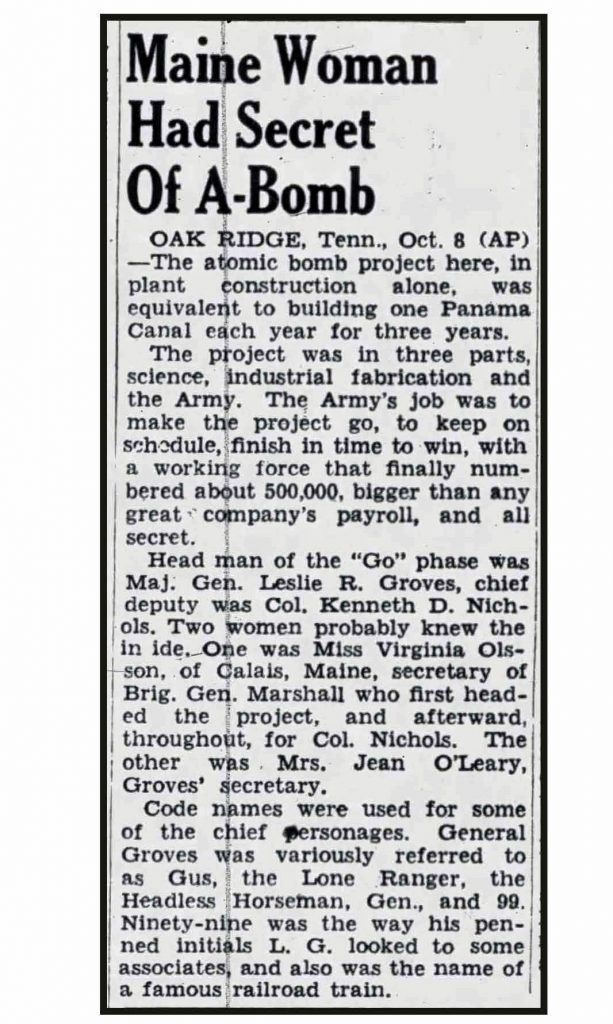

Maine Woman Had Secret Of A-Bomb

OAK RIDGE, Tenn., Oct. 8 (AP) [1945]

The atomic bomb project here, in plant construction alone, was equivalent to building one Panama Canal each year for three years.

The project was in three parts, science, industrial fabrication and the Army. The Army’s job was to make the project go, to keep on schedule, finish in time to win, with a working force that finally numbered about 500,000, bigger than any great company’s payroll, and all secret.

Head man of the “Go” phase was Maj. Gen. Leslie R Groves, chief deputy was Col. Kenneth D. Nichols. Two women probably knew the inside. One was Miss Virginia Olsson, of Calais, Maine, secretary of Brig. Gen. Marshall who first headed the project, and afterward, throughout, for Col. Nichols. The other was Mrs. Jean O’Leary, Groves’ secretary.

Code names were used for some of the chief personages. General Groves was variously referred to as Gus, the Lone Ranger, the Headless Horseman, Gen., and 99. Ninety-nine was the way his penned initials L. G. looked to some associates, and also was the name of a famous railroad train.

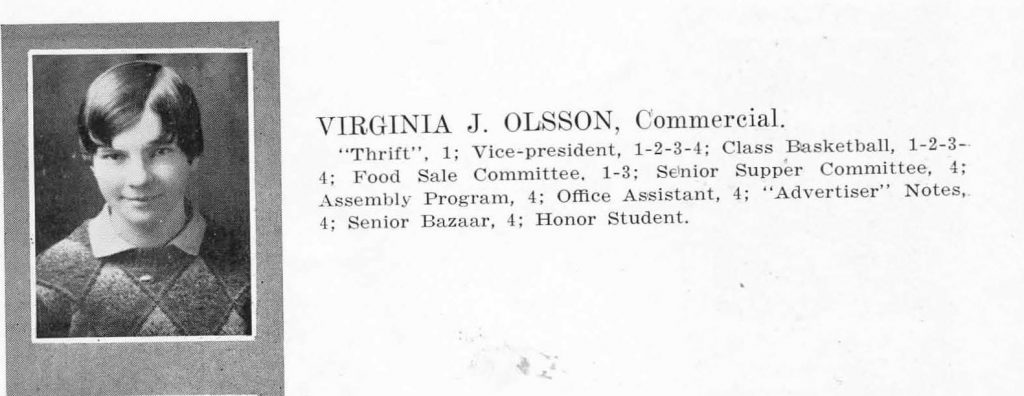

Virginia Olsson was born in 1913 in Calais to Olaf and Eva Griffin Olsson–who died in 1927 within two weeks of each other. We don’t know the circumstances surrounding their deaths, but it must have been traumatic for Virginia and her brother Orville. We know little about her life growing up in Calais although information provided by a niece says “my Dad and Aunt Virginia were brought up by the Goodes…” and a notice in the social column of the Bangor Daily in 1959 says “Guests at the home of Ruth, Marion and Margaret Goode have been Miss Virginia Olsson of Washington D.C. and Mr. and Mrs. Arthur Poulin….” which seems to confirm the relationship. She attended Calais Academy and is first mentioned in the yearbook in 1929 as the assistant literary editor of the yearbook.

The Olsson family built this brick block for Penney’s in 1928. Virginia worked in Olsson’s Clothing Store on the right in 1931.

Virginia graduated from Calais Academy in 1930 and went to work in her uncle’s, Nils Olsson’s store, on Main Street. The Olsson family was Swedish and came to Calais in the early 1900s. Four of them were involved in construction and business: Carl, Nils, Olaf and Oscar. Carl was a master builder who developed a concrete which was, it is claimed, stronger than any before known. Most will recognize the store above as most recently Johnson’s Hardware which was destroyed by fire in 1996.

Olsson’s Garage is to the far left. The Knight Memorial Church was directly across Main Street from the end of Monroe Street.

The Olssons bought the land on Main Street on which they built the Penney’s Building in the 20’s and originally built the garage just visible above but the coming of the chain stores to Calais presented the family with the opportunity to lure Penney’s to town.

The Olssons demolished the gas station and built the Penney’s brick block in 1928. The right-hand half of the building was a clothing store operated by the merchant brother of the family, Nils, and Virginia went to work there in 1931 after graduation from Calais Academy. This part of the building became Johnson’s Hardware; and later, Rocky and Andy Johnson bought the other half and expanded their business.

In 1909 the family constructed the Olsson Block across the street and just up from Monroe. It has long been and remains a jewelry store, so Virginia was not without opportunities in Calais after her 1930 graduation. However, in 1932 she attended Beal Business College in Bangor and in 1933 the Maine School of Commerce. She returned to Calais briefly in 1935 as a teacher. Her bio from the 1935 yearbook:

Virginia Olsson is teaching commercial studies at Calais Academy, Shorthand, Typewriting, Commercial Arithmetic, and English.

Calais Academy, 1930; Beal College, Bangor, Maine, 1933; Beta Phi Sorority; Member Student Council; Leader of Girl Reserve Group; Practice teaching at the school. Miss Virginia Olsson, also a graduate of Calais Academy and of Beal College in Bangor, has been with us since September, teaching Commercial subjects.

Virginia apparently gave up teaching and went to work in administration at the Quoddy Project in Eastport. She remained there through 1936 when she moved to New York City and where she worked in the Civil Service until, we presume, she was called to the service of her country during the war. She remained in the employ of Major General Nichols after the war and lived in Washington D.C. until her retirement. She died October 15, 1999 and is buried with her parents in the Calais Cemetery. She is listed on the roles of Calais veterans of the war as “Virginia Olsson Atomic Bomb Project”.

We will never know how living in such a rarefied atmosphere of excitement and secrecy influenced her choices in life. She never married and continued to work for General Nichols after the war. He remained in the military, taught at West Point, headed several top-secret weapons development programs and became general manager of the Atomic Energy Commission. Later he worked privately as a consultant on nuclear power plants. He was the youngest major general in the army when he achieved the rank in 1948. He died in 2000, a year after Virginia. She, of course, could not write or confide in close friends regarding her life’s work; even after the war Nichols’ work was highly classified, and Virginia would have been vetted constantly to maintain her security clearance. As she spent her life in the shadows, we don’t know much about her but she had an insider’s view of some of the most important historical events in the country’s history.

A couple of codas:

Bob McCarter of Red Beach had a bird’s eye view of the culmination of the project on which Virginia worked during the war. He was a WW II fighter pilot in the Army Air Force flying P-47 Thunderbolts and later P-51 Mustangs in the Pacific with the 348th Fighter Group, 341st Fighter Squadron.

He was on a mission off Okinawa on August 9, 1945, when a brilliant flash of light startled him. When he returned to his land base, he learned that he had seen the atomic bomb explosion that devastated Nagasaki.

Another local who was involved in the Manhattan Project was Chalmers Jack McKenzie of St. Stephen,

who was the President of the National Resource Council of Canada during the war. His war work according to the Canadian Encyclopedia included:

The tenfold expansion of the NRC Laboratories, top-secret war gas, aviation, radar and atomic bomb research, membership on the US-British-Canadian Combined Policy Committee, allocating uranium supplies, and even the chore of telling Winston Churchill that “Habakkuk,” the British Prime Minister’s pet project of an iceberg-aircraft carrier, was impossible.

Finally, a couple of weeks ago we wrote of the Red Beach Horror. We speculated that Fred Reynolds, being found not guilty of the murder of his wife and children by reason of insanity, was incarcerated at the Maine Insane Hospital in Augusta. A researcher with more skill than we possess reports this was only partially correct. Reynolds was initially committed to the Insane Department of the State Prison in Thomaston but escaped. Upon being captured he was committed to the Augusta Mental Health facility where he died in 1924.