It was the 1820’s before what passed as roads in the St Croix Valley were improved enough for stage travel. According to Herb Silsby of Ellsworth:

“Prior to 1825 there were no stage coaches in Downeast Maine, because the roads were so terrible. After that date, however, the roads had improved to the point that it was possible for a carriage to get around pretty well.

There were three famous types of wagons and these coaches were really just glorified wagons. There was the Conestoga wagonthat was used to carry settlers on the westward journey to California and Oregon, Troy wagons, and the most famous of all, the Concord Coach.

The Concord Coach, made in New Hampshire, was immediately very popular because it was so much more comfortable than the Troy wagons. This is the kind of carriage you see in all the old movies. They were rugged, and they kept improving them, so they were in use right up through World War I.

The first Concord Coach was built in 1828, and cost about $1400. They came in a variety of sizes. In the bigger ones, one passenger could sit next to the driver, six could sit inside, and you could load up the roof with more passengers in good weather. They used leather straps for springs. This wasn’t great, but it was wonderful compared to everything else.”

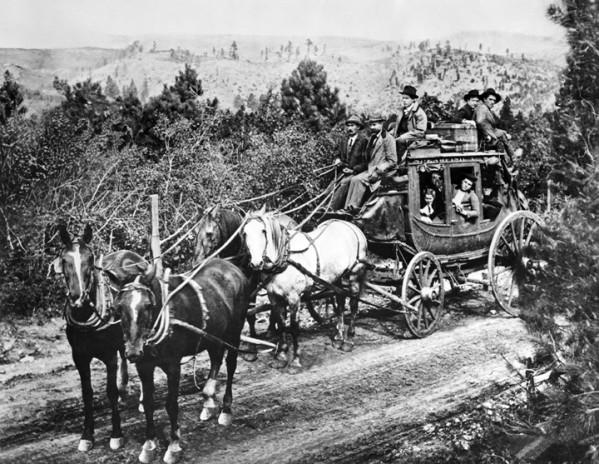

The photos above show the famous 1846 Bangor-Machias- Calais Concord coach which traveled the Shore Route (Bangor Ellsworth Machias Calais) for many decades.The history of this stagecoach would require a book but anyone interested in taking a ride in the coach could probably talk the owner into selling it for somewhere around a million dollars, its value on today’s market. It is currently in the Cowboy Museum in Wapiti Wyoming.

There was no such concept as “overbooking” during stagecoach days and passengers became pretty familiar with each other by the end of any stagecoach trip. The Shoreline Route from Ellsworth to Calais took 36 hours on average. To minimize friction some interesting rules of stagecoach etiquette were developed:

- The best seat inside a stagecoach is the one next to the driver… you will get less than half the bumps and jars than on any other seat. When any old “sly Eph,” who traveled thousands of miles on coaches, offers through sympathy to exchange his back or middle seat with you, don’t do it.

- Never ride in cold weather with tight boots or shoes, nor close-fitting gloves. Bathe your feet before starting in cold water, and wear loose overshoes and gloves two or three sizes too large.

- When the driver asks you to get off and walk, do it without grumbling.

He will not request it unless absolutely necessary. If a team runs away, sit still and take your chances; if you jump, nine times out of ten you will be hurt.

- In very cold weather, abstain entirely from liquor while on the road; a man will freeze twice as quick while under its influence.

- Don’t growl at food stations; stage companies generally provide the best they can get. Don’t keep the stage waiting; many a virtuous man has lost his character by so doing.

- Don’t smoke a strong pipe inside especially early in the morning. Spit on the leeward side of the coach. If you have anything to take in a bottle, pass it around; a man who drinks by himself in such a case is lost to all human feeling. Provide stimulants before starting, ranch whisky is not always nectar.

- Don’t swear, nor lop over on your neighbor when sleeping. Don’t ask how far it is to the next station until you get there.

- Never attempt to fire a gun or pistol while on the road, it may frighten the team; and the careless handling and cocking of the weapon makes nervous people nervous. Don’t discuss politics or religion, nor point out places on the road where horrible murders have been committed.

- Don’t linger too long at the pewter wash basin at the station. Don’t grease your hair before starting or dust will stick there in sufficient quantities to make a respectable ‘tater’ patch. Tie a silk handkerchief around your neck to keep out dust and prevent sunburns. A little glycerin is good in case of chapped hands.

- Don’t imagine for a moment you are going on a picnic; expect annoyance, discomfort and some hardships. If you are disappointed, thank heaven.

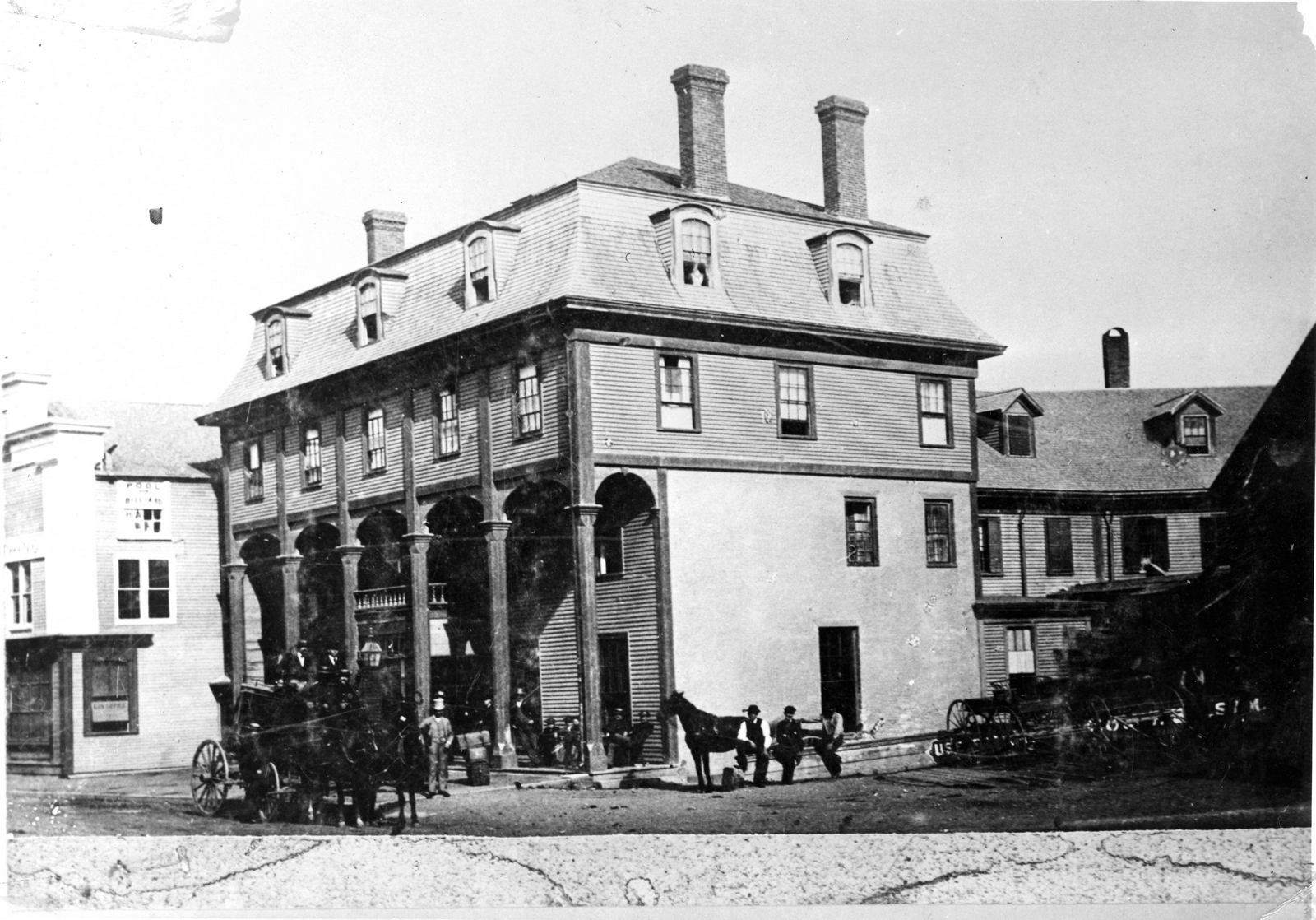

Rule number 10 cannot be too strongly emphasized. The photos above show stages possibly about to begin a return journey from Calais to Bangor from the St. Croix Hotel in Calais via the Shoreland Route. A very unhappy traveler described this journey in a newspaper article in 1834:

Rule number 10 cannot be too strongly emphasized. The photos above show stages possibly about to begin a return journey from Calais to Bangor from the St. Croix Hotel in Calais via the Shoreland Route. A very unhappy traveler described this journey in a newspaper article in 1834:

The only way to travel from Calais to Bangor after the freeze was by the United States Mail stage. This journey was definitely not for the fainthearted. A description of the trip is given in the Calais Frontier Journal of January 8, 1834. The writer was described as a merchant of high standing from Boston. According to the letter the stage left Bangor at 2:30 P.M. and arrived at Ellsworth at 7 P.M. where the passengers spent the night. The accommodations and fare were suspect and overpriced. According to the merchant “ on this route passengers are made for the hotels and not hotels for the passenger.” At three the next morning the passengers were awakened and at four, without breakfast, they started for Cherryfield where they arrived at 9 or 10 A.M. if traveling was good. The merchant complained “It is not very pleasant getting up and starting off at 3 o’clock, when the mercury is from 10-20 degrees below zero. But to be driven until near noon without breakfast is a great cruelty and should be an indictable offense among Christian people.” The travelers were given lunch and supper within the next 4 hours and loaded into an open two horse pung at Machias. A pung is an open sleigh with a box shaped body, certainly not a conveyance designed for comfort especially in below zero weather as the passengers have no protection from the elements. At Dennysville the Eastport passengers are unloaded into a one horse pung for the trip to Eastport. The Mail then proceeded to Calais where it arrived at about 2 A.M. The return trip to Bangor was even more gruesome. It began in Calais around 2 A.M. and Eastport at 4 A.M. and was delayed at Dennysville while mail was distributed. There was no public house in which to wait and the merchant justly complained “This is very painful when one is already nearly frozen.” The mail stage did not reach Ellsworth until midnight. The trip from Calais to Bangor took nearly 36 hours, much of it in an open sleigh in sub zero weather. Its little wonder the merchant warned that Ladies and persons not well should not take the mail line until warmer weather sets in.

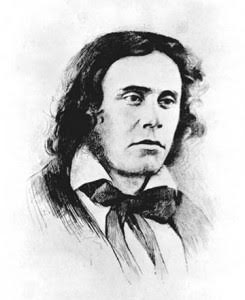

One of the more famous travelers over the Shoreland Route was Richard Henry Dana, author of Two Years Before the Mast, a classic memoir of sailing around the Horn to California in 1834. Traveling from New Brunswick in 1851 he took the ferry from St. Andrews to Robbinston and caught the stage west.

He left Robbinson July 31, 1851, at 9:30 in the morning in a “mail wagon” on his way to Bangor. At Pembroke, he transferred to the stagecoach from Eastport. He had an outside seat up with the driver. He rode from Pembroke to Cherryfield on one line and from Cherryfield by way of Ellsworth to Bangor on another. He arrived at Cherryfield at a half hour past midnight. He had poor lodgings, an early breakfast and rode to Bangor via Ellsworth.

Dana spent a good part of the trip talking with the drivers. The driver from Machias to Cherryfield he found to be a sober, sedate man and a firm believer in female virtue and excellence. In contrast the driver from Pembroke to Machias was a “regular libertine.” Dana wrote that if the driver’s “account of the state of things along the road, if half true, shows that female virtue in the country towns of Maine is no better than in the South Europe.”

His tedious trip was also broken up by the antics of an old woman on her way to Bucksport from Pembroke. She questioned every driver and passenger repeatedly about changing stage coaches at Ellsworth. She pleaded poverty, and whined and moaned about paying her bills at the taverns for meals and overnight lodgings and was let off at half price. The inside passengers took up a collection for her to get to Bucksport. Nonetheless she begged and got a free ride from Ellsworth to Bucksport on the grounds she had not one cent to pay her fare. The other passengers decided she was a “mere sponge,” and Dana reported that there are such people “among the vulgar, mean, half-witted old women of country towns.”

Some of the larger coaches had three seats, the one in the middle being most undesirable. When crowded even a modicum of comfort could only be provided by “dovetailing” the passengers legs. This practice was not always agreeable to female passengers such as Mrs Peck of Illinoy:

When a coach contained three seats, each of which accommodates three passengers; those on the centre, and the three with their backs to the horses, face each other, and, from the confined space, the arrangement and mutual convenience of leg-placing not infrequently leads to fierce outbreaks of ire. A fat old lady got into the coach at Peoria, whose uncompromising rotundity and snappishness of temper, combined with a most unaccommodating pair of “limbs” (legs, on this side the Atlantic), rendered her the most undesirable vis-a-vis a traveler could possibly be inflicted with. The victim happened to be an exceedingly mild Hoosier, whose modest bashfulness prevented his remonstrating against the injustice of the proceeding: but, after unmitigated sufferings for fifty miles, borne with Christian resignation, he disappeared from the scene of his martyrdom, and his place was occupied by a hard- featured New Yorker, the captain of one of the Lake steamboats, whose sternness of feature and apparent determination of purpose assured us that he had been warned of the purgatory in store for him, and was resolved to grapple gallantly with the difficulty. As he took his seat, and bent his head to the right and left over his knees, looking, as it were, for some place to bestow his legs, an ominous silence prevailed in the rocking coach, and we all anxiously awaited the result of the attack which this bold man was evidently meditating; the speculations being as to whether the assault would be made in the shape of a mild rebuke, or a softly-spoken remonstrance and request for a change of posture.

Our skipper evidently imagined that his pantomimic indications of discomfort would have had a slight effect, but when the contrary was the result, and the uncompromising knees wedged him into the corner, his face turned purple with emotion, and, bending towards his tormentor, he solemnly exclaimed-“I guess, marm, it’s got to be done anyhow sooner or later, so you and I, marm, must jist ‘dovetail.’ ”

The lady bounded from her seat, aghast at the mysterious proposal. ’’Must what, sir-r?”

’’Dovetail, marm; you and I have got to dovetail, and no two ways about it.”

’’Dovetail me, you inhuman savage’” she roared out, shaking her fist in the face of the skipper, who shrank, alarmed, into his corner; ’’dovetail a lone woman in a Christian country! if thar’s law on airth, sir-r, and in the state of Illinoy, I’ll have you hanged!

“Driver, stop the coach,” she shrieked from the window; “I go no farther with this man. I believe I ar’ a free ‘ooman, and my name is Peck. Young man,” she pathetically exclaimed to the driver, who sought to explain matters, whilst we, inside, were literally convulsed with laughter, “my husband shall larn of this, as shure as shooting. Open the door, I say, and let me out!” And, spite of all our expostulations, she actually left the coach and sought shelter in a house at the road-side; and we heard her, as we drove off, muttering “Dovetail me, will they? the Injine savages if ther’s law in Illinoy, I’ll have him hanged!”

It is unnecessary to say that “dovetailing” is the process of mutually accommodating each other’s legs followed by stage-coach and onmibus passengers; but the term-certainly the first time I had ever heard it used in that sense-shocked and alarmed the modesty of the worthy Mrs. Peck of Illinoy.

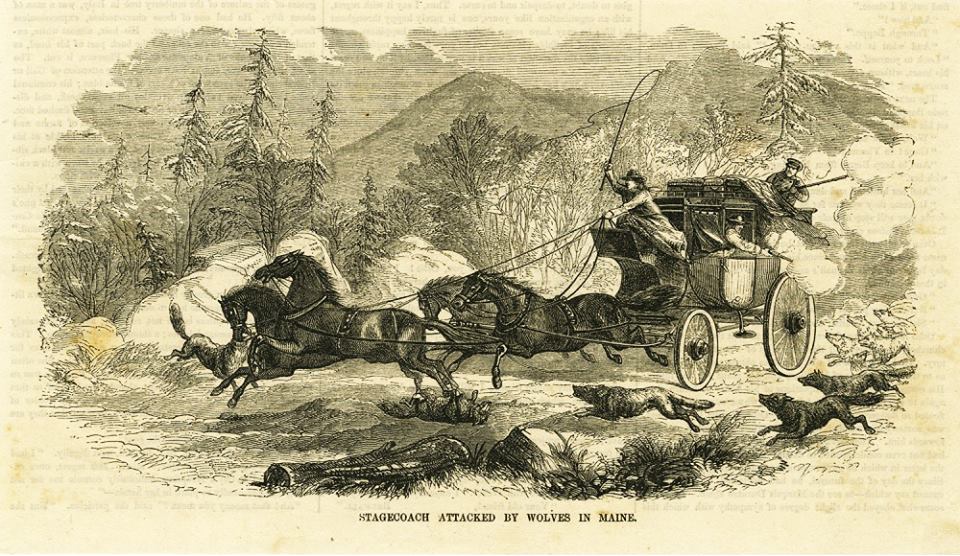

The above focused mainly on the first stagecoach line Downeast, the Shoreline Route through Ellsworth. In the late 1850’s George Spratt of Bangor managed to obtain the mail contract over what became known as the “Airline”. It cut many hours off the journey and into the pockets of the owners of the Shoreline Route. They retaliated with what we now know as “false news” claiming the Airline Stage passengers would be eaten by wolves before they reached Wesley. The papers were full of planted stories of this dangerous journey with lots of graphics like the above but the Airline stage was soon full of passengers thrilled with the prospect of shooting a wolf on the way to Calais.

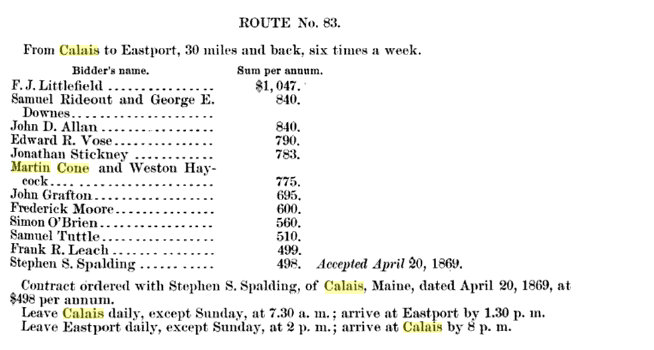

The above focused mainly on the first stagecoach line Downeast, the Shoreline Route through Ellsworth. In the late 1850’s George Spratt of Bangor managed to obtain the mail contract over what became known as the “Airline”. It cut many hours off the journey and into the pockets of the owners of the Shoreline Route. They retaliated with what we now know as “false news” claiming the Airline Stage passengers would be eaten by wolves before they reached Wesley. The papers were full of planted stories of this dangerous journey with lots of graphics like the above but the Airline stage was soon full of passengers thrilled with the prospect of shooting a wolf on the way to Calais. Some idea of how long a stagecoach journey was in those days can be seen above. Martin Cone of Calais bid, unsuccessfully, on the Calais to Eastport mail contract in 1869. The 30 miles to Eastport took 6 hours each way, not much above a walking pace.

Some idea of how long a stagecoach journey was in those days can be seen above. Martin Cone of Calais bid, unsuccessfully, on the Calais to Eastport mail contract in 1869. The 30 miles to Eastport took 6 hours each way, not much above a walking pace. Finally a nice photo of one the Holmes family getting out of a stagecoach in front of the Homestead on Main Street, Calais. We wish we could identify her. She appears to be returning from a long journey given the amount of luggage on the coach. Across the street is the building many will remember as the Charles Hotel.

Finally a nice photo of one the Holmes family getting out of a stagecoach in front of the Homestead on Main Street, Calais. We wish we could identify her. She appears to be returning from a long journey given the amount of luggage on the coach. Across the street is the building many will remember as the Charles Hotel.